What do you think?

Rate this book

120 pages, Paperback

First published February 13, 1947

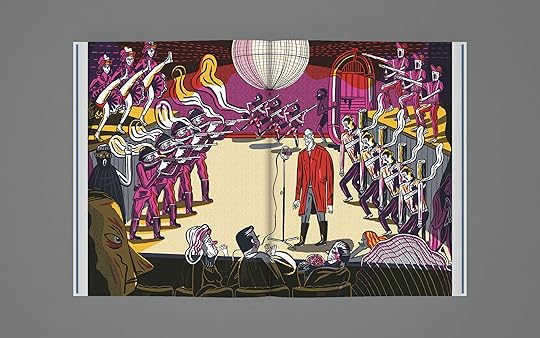

Ich weiß, es ist schwer, mir zuzuhören und mit mir zu fühlen.Wolfgang Borchert made me feel that way from beginning to end of this short, yet seemingly interminably long, anthology of a play and short stories. It was as if I were privy—which seems like the wrong word, as does forced—to witness a long, desperate, inconsolable primal scream. Borchert’s howl is about the injustice of war, or more precisely, the injustice of being forced to fight, witness and survive the horrors of war. I took it in with short gulps of reading and needed a break between each piece.

(I know it’s difficult to listen to me and to feel with me.)

Wir sind die Generation ohne Bindung und ohne Tiefe. Unsere Tiefe ist der Abgrund. Wir sind die Generation ohne Glück, ohne Heimat und ohne Abschied. Unsere Sonne ist schmal, unsere Liebe grausam und unsere Jugend ist ohne Jugend. Und wir sind die Generation ohne Grenze, ohne Hemmung und Behütung—ausgestoßen aus dem Laufgitter des Kindseins in eine Welt, die die uns bereitet, die uns darum verachten.* The translation in English, The Man Outside, loses too much of the “outside the door” symbolism and diminishes, in my view, what Borchert intended. Imagine desperately trying to get on the other side of a door and knowing you will never make it.

(We are the generation without bonds and without depth. Our depth is the abyss. We are the generation without luck, without a home or without a proper parting. Our sun is narrow, our love dreadful and our youth is without youth. And we are the generation without limits, without scruples or secrets—locked out of the children’s playpens that prepare us for the world, and for that we are despised.)