What do you think?

Rate this book

351 pages, Paperback

First published October 3, 2013

- The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI).Wikipedia article with latest exoplanet count:

- The probabilities of extra-terrestrial life (longevity of intelligent life is most important variable, and difficult to estimate, in determining likelihood of intelligent life existing concurrently within the same galaxy.)

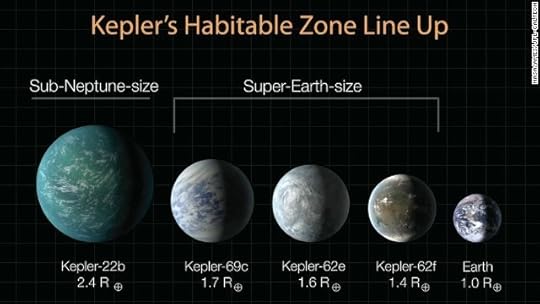

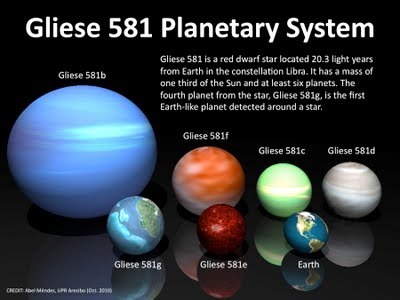

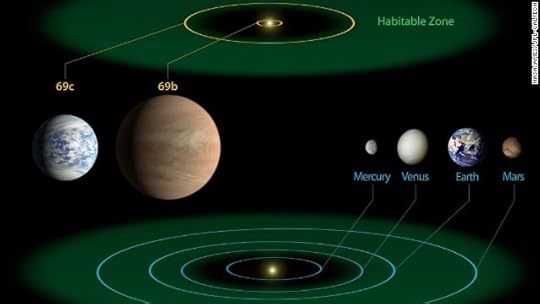

- Recent success in finding planets around other stars (exoplanets).

- Using radial-velocity spectroscopy (measuring the wobble) or the transit of planets in front of their stars to calculate number size and orbit size of exoplanets.

- Description of fierce competition between astronomers to find planets (even claims of stealing information).

- Stories told about past efforts to observe the transit of Venus.

- Calculation of the monetary value of a world (the reality of limited resources makes this analysis necessary to help in making decisions regarding where to invest research money)

- Description of the geologic history of the earth

- Description the the history of life on earth

- Description of what we know about history of earth’s atmosphere, temperatures and probable cause of future global warming

- Description of geologic history of Marcellus shale formation in northeastern USA.

- Story of the history of science from ancient Greeks to modern days.

- Explanation of the carbon/silicate interaction in the Archean atmosphere to prevent runaway greenhouse effect like that on Venus.

- History of rocket science and the demise of NASA's future space exploration plans.

- Possible strategies of using technology to reduce expensive rocket launch costs.

- Biographic sketch of Sara Seager, MIT Professor of Physics and Planetary Science.

[I]t was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind…, and that everything…was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.