What do you think?

Rate this book

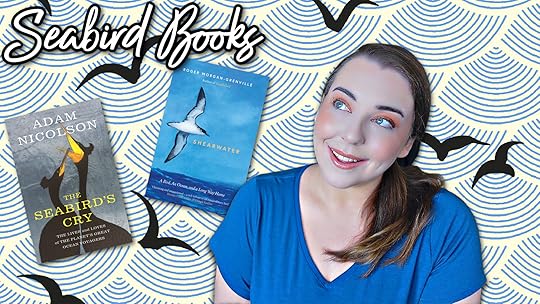

416 pages, Hardcover

First published June 1, 2017

"a sprung and beautiful thing, dawn grey, black eyes, black tips to the wings . . . its whole being like a singer’s held note, not flickering or rag-like, nor blown about like a tern, but elastic, vibrant, investigative, delicate . . . "I find that completely pretentious. I love kittiwakes, but I cannot stand that description, it's grasping, unnecessary and off-putting. I do not want to read that puffins carry themselves with "Edwardian propriety", or of the otherwordliness of the wandering albatross or that they inhabit a different, higher spiritual realm than us (ugh wtf). Nicolson is guilty of such description in almost every page.