What do you think?

Rate this book

421 pages, Kindle Edition

First published September 12, 2017

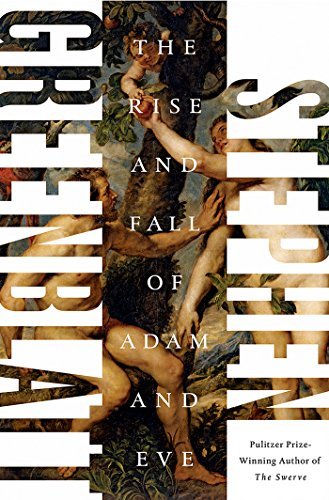

“And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat.” It is this transgression—a deliberate action, not an impersonal, mechanistic process of random genetic mutation and natural selection—that determined the shape of our lives. The Adam and Eve story insists that our fate, at least at the beginning of time, was our own responsibility. Millions of people in the world, including many who grasp the underlying assumptions of modern science, continue to cling to the peculiar satisfaction that the ancient story provides. I do. (My italics)