Creative Evolution (1907) is arguably Henri Bergson’s most matured and comprehensive account of reality. In it, he draws heavily from his earlier works Time and Free Will (1889) and Matter and Memory (1896), and intertwines his views on time, space, matter and mind with the (then new) evolutionary biology. The result is a very original framework with which to view the world.

Bergson won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1927, and this is a very important landmark. It shows Bergson’s artistic talents and his philosophical genius. But it is important in another sense: Bergson was no real philosopher – at least in the sense philosophy is usually understood – but more of an artist. Perhaps, some might even call him a secular theologian. Anyway, if you have to compare Bergson to some predecessor, Plotinus comes to mind. Why? Plotinus drew from Plato, Neo-Platonism, Stoicism and a myriad other source, and drew up a total worldview in which the concept of ‘immanence’ was all-important.

Likewise, Bergson draws up a whole philosophy, borrowing ideas of Descartes, Kant, modern physics and modern biology to synthesize a grand worldview, ultimately based on the notion of ‘intuition’. Both Plotinus and Bergson place a high value on the immanence of the world – reality is that which immediately shows itself to us – intuitively, so to speak. All attempts to describe, explain or conceptualize reality leads to distorted, disfigured views of the world.

There are major differences between Plotinus and Bergson, though. The most important being that Plotinus – steeped as he was in Ancient philosophy – recognized the gradualness of reality. The Whole of reality – i.e. God – is perfectly immanent, but all of its parts partake in this whole, leading to a ladder of reality, on which mankind is placed somewhere between dead matter and God. We are gifted with mind, yet we also are partly material.

For Bergson, this gradualness of reality is the product of a habitual illusion. Most of the history of philosophy (and certainly all of the old debates) is riddled with this illusion of gradualness. Plato’s theory of Forms and Aristotle’s First Mover are postulates, necessary because reality is conceived to be immutable. Greek philosophy, as modern science, saw itself confronted with a world that is composed of moments, states and forms. These are simply parts – the mind immediately leads us to the concept of a whole – a series of moments, a sequence of states, an order of forms. It is these series that were (and are) conceptualized as eternal Forms, Prime Movers or mathematical equations.

All of the old philosophical debates are then reduced to mere pseudo-problems, as products of the habits of our mind. Understanding our mind properly would then lead to dissolving of all these problems. It is this that Bergson attempts in all of his works. Or rather: it is his main aim. It is in this domain that Bergson’s philosophy is truly unique, impressive and baffling.

With the risk of oversimplifying Bergson’s theories, this is Bergson’s account of the world.

Drawing on Descartes’ dualism, Bergson claims there is matter and mind. Matter is the objective world that confronts us during our conscious life. Mind is our intuitive sense of reality. Usually, philosophers would attempt to place perception and/or intellect in the sphere of the mind. Not for Bergson. He claims perception is simply the prolongation of material movements – tendencies. Tendencies of what? Of our bodies. Our bodies are peculiar, in the sense that they are material objects, yet also are intrinsically connected to our inner consciousness. This is what distinguishes us from dead matter, plants, and animals.

Seeing as there are consciousness and physical bodies, our lives come with two aspects. Normally, most of the time, we are simply physical bodies, solely occupied with practical life. We perceive, we act. Scientists study the human body and can describe how physical movements transmit energies to our sense apparatus, which relates these impulses to our brains. Our brains then send out transmissions as a result of these movements. In short: our brain is the centre, receiving and sending messages to our peripheral bodily locations. For Bergson, the human body – as indeed the bodies of all living organisms – is nothing but a sensory-motor system.

But, as said, human beings have consciousness. That is, we are not simply machines operating on the principle of stimulus-response. And so it is with most ‘higher’ animals. Apart from perception, we have intellect. This is the ability to deduce and induce new data from given data. Ultimately, these rest on geometrical and logical principles, which themselves are the foundation of both our common sense grasp of reality and our scientific theories (like the conceptions of space and time in physics). With Bergson, intellect is placed firmly in the bodily organism.

To explain both perception and intellect, Bergson draws on evolutionary biology – these faculties are adaptations of organisms that allow for goal-directed behaviour. In short, he uses a functionalist approach when explain both our perception and intellect.

So how does it answer the above mentioned philosophical problems? Well it doesn’t – yet. These philosophical debates and problems (mostly metaphysical) are the results of this biological way of thinking. We are animals, living social lives. We use language to communicate with others; language uses symbols that refer to particular objecting and things in the world; and this mechanism forces a particular, physical way of thinking on us. We conceptualize reality as a collection of parts (objects, things) and their relations, and express it to others. While this worldview has obvious evolutionary value – otherwise we wouldn’t think this way and hadn’t changed the world so profoundly – it is a distorted view of the world. It tricks us into believing we have perceived reality, yet the metaphysical implications of this worldview should warn us (or have warned us) about the illusoriness of this approach.

For Bergson, this material world is simply a natural product of evolution.

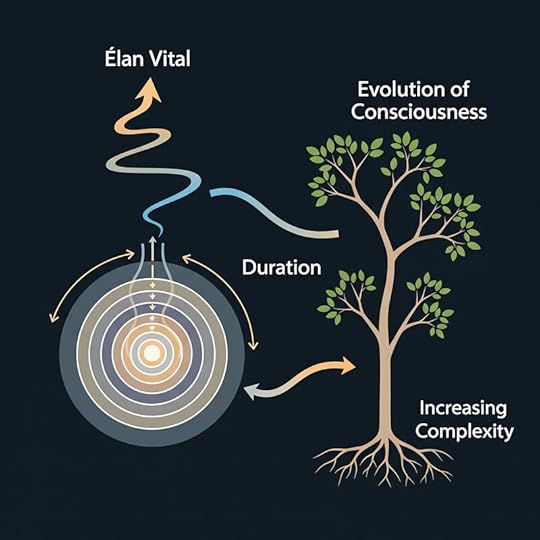

The task of the philosopher is to deconstruct it, and to unravel the true way of the world. When we talk about consciousness, or life, we are moving in a totally different region. We should un-learn the intellectual way of viewing the world – of chopping it up into infinite collections of moments, states, and forms. In Time and Free Will (1889), Bergson attempted to show that psychologists look at human consciousness as a collection of quantitative states, while it truly is a continuous flow of qualitative states. Measuring, or even conceptualizing any state artificially destroys the continuity, movement and quality of the very thing the psychologist tries to study. Consciousness is duration – a totally different region from the objective space-time in which the scientist (as well as the common sense person) operates. Or rather, all spatial and temporal ideas are intellectual constructs, attempts at intellectually grasping un-graspable intuitions. E.g. we imagine duration as moments, which can be pictured to ourselves as (an infinite collection of) points on a line. Yet this picture is a geometrical representation of an intuition – it quantifies a qualitative state.

Likewise, in Matter and Memory (1896), Bergson attempted to show that picturing the world as (infinite) collections of moments, states and forms, is simply the product of the correlation of our consciousness and the material world (including our brains). Scientists and philosophers have debated for ages (and still do) how physical brain states relate to conscious states. There seems to be an unbridgeable chasm between the objects of neuroscience and psychology. Bergson’s theory is that this is a pseudo-problem, the result of our intellectual way of viewing the world (including ourselves). Intuitively, we experience our body in the here and now. We are (paraphrasing him) a personal entity continuously eating our way into the future. We literally our only here and now, and our whole notion of past and future comes from our memory. That is, we are built to learn from past experiences. This means we adapt ourselves to our current situation based on prior events. Physically, this is simply the formation of tendencies in the brain.

Psychologically, this past does not exist. All we are, is our current (qualitative) state, which itself is a continuously moving intuition. Pure duration. That is, prior states are selected – based mostly on practical needs, sometimes on speculative desires – and are immediately fused with our present state. Even this way of putting it stunts the meaning of Bergson: he literally means there is no conscious past. All selected memories are not memories of events as they happened – they are intrinsically part of the present. The past never comes back, what we believe to be memories of the past, are our present states fusing (selectively) past states with current states, leading to totally new states. In short: consciousness continuously creates states out of current and past experiences.

Similarly, there is no future. Due to the workings of our memory, we form notions of a past, as distinguished from the present. Now, this seems to lead us also towards a future. If I was, and now am, during those past moments, the current ‘I’ was part of the (‘my’) future. But this is an illusion. Just like there is no (conscious) past, there is no (conscious) future. There is simply me, as pure consciousness, experiencing a continuous flow of ever-changing states.

(I am aware of my creaky description of this mechanism – Bergson is already struggling to express it in a 300 page book, and given my very limited way of expression this only greatens the problem. Once you grasp it, is easy to see who he means…)

And now we have hit upon Bergson’s deepest insight. There is a dualism between inner consciousness and external materiality. The first is the real of pure duration, continuity, movement; the second is the realm of our brain, physical body, all of Nature. Due to language and social life, we express the second realm in terms of objects and their relations in space-time. Our intellect, so used in viewing the world in this way, internalizes this worldview and intellectualizes our intuitions, so to speak. We quantify qualitative states of consciousness; we transform movement into immobility; we represent time and movement as (infinite collections of) points in space-time.

So far, all we have dealt with are Bergson’s main theories from Time and Free Will (1889) and Matter and Memory (1896). What does this have to do with Creative Evolution (1907)? Well, like I mentioned at the beginning of this review: it is his magnum opus. He takes all of his earlier ideas and synthesizes them with evolutionary biology.

The biologist – assuming the unprovable notion that he has the same intellectual and perceptive faculties as his fellow human beings – falls into the same trap as the physicist, psychologist and common sense person. He studies living organisms. Life is a central concept here: What distinguishes living organisms from dead matter? He will explain this in terms of biochemical processes, and trace this line of development back into the remote past. Really, life is nothing but the active collection of energy to transform it into something new.

The plant collects energy from the sun, carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and water from the soil, in order to produce carbohydrates. It is nothing but a transformation (with an emphasis on form) of energies. This type of living is rather basic. In the past, certain organisms developed ways to outsource this type of living (to plants) and to eat the organisms (plants) that transform energies. So animals eat plants to collect energy, in order to produce movement (to collect energy, etc.). Now, this leads to organisms competing for resources – plants for sunlight and water, animals for plants or other animals – so an arms race of protective apparatus. And this leads to better weaponry to best these protections. Etc.

In short, we see life developing from stationary plant life to moving animal life. Sensory-motor systems become a necessity for animals, guided under the principle of natural selection. Now it starts to pay to interfere with goal-setting, flexibility becomes a premium, resulting ever higher specialization of intellectual capabilities. In short: life branches out, organisms find unique ways of adapting themselves to their ever-changing environment, and intellect becomes one of these adaptations. An ever expanding intellect, due to ever expanding cortical specialization, leads, ultimately, to man.

Bergson claims that man is unique, of a different kind, compared to all other organisms. While instinct, perception and intellect are gradual properties, possessed by many organisms in some way or other, it is only in man that life manifests itself, to itself. That is, man is himself a state of this ever-flowing, continuous line of development – a state of life – but at the same time he is able to grasp this way of being intuitively. Other animals, supposedly, lack this capacity. The horse might be intelligent in remembering his care taker and the times it is fed, but it doesn’t intuitively grasp that it’s alive. Man does.

Now, we can wrap up all of Bergson’s theories rather easily. Just like (pure) consciousness is a totally different region from the material world, so life is a totally different region from the natural world. For Bergson, life is a primordial impulsion, given to dead matter – enlivening matter, so to speak – which then sets of a continuous ever-flowing chain of explosions, moving endlessly in all directions. This leads to the endless tree of life, of which we are simply one state.

The biologist – still driven by the same sort of essentialist thinking of Aristotle or formalistic thinking of Plato – artificially chops up this tree of life in his pursuit of distinct varieties and species. He looks for essences and static forms in qualitative, ever-moving forms of life. What is a Siberian tiger? When does an organism qualify to be a Siberian tiger? What are the essential traits an organism has to have to qualify as a Siberian tiger? These questions, ultimately, are unanswerable, since they simply depend on our own linguistic conventions. Just like the quip that ‘IQ is what the IQ test measures’ we can say ‘A Siberian tiger is what the biologist decides to measure’.

------------------------------------------------

(final paragraphs continue in comment section.)