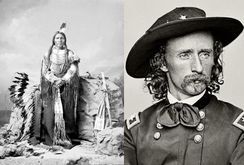

Custer and his immediate antecedents were consummate crackers. Jacksonian Democrats, American expansionists spoiling for a war, any war. Settled long enough and far enough East to entertain romantic, Fenimore Cooper-ish images of Noble Red Men, but made impatient by the independence of the tribes that still existed, on the land still to be taken by whites. Northerners, and loyal Unionists when the time for fighting came, though untroubled by slavery while it existed, and absolutely opposed to black suffrage after it was abolished; white supremacists, back when the sentiment was taken for granted and uncontroversially expressed; “Christian soldiers” (as Papa Custer called George and his younger brother Lt. Thomas Custer, who once charged ahead of his men, leapt into the midst of Confederate troops, and didn’t let being shot in the face by the rebel regiment’s color bearer daunt him from quickly dispatching that adversary and wresting away the stars-and-bars; during the Civil War Tom won the Congressional Medal of Honor twice) who had been indoctrinated to believe that the United States of America “was uniquely blessed, had the finest government ever conceived by man, was the freest the world had ever known, and had a Manifest Destiny to overspread the continent.”

Ambrose has a deep sense of nineteenth century political affiliations, and of the particular career ramifications of Custer’s chosen affiliations. As an anti-black Democrat who hoped to see the broken South treated with delicacy, he was out of place, when the Civil War ended, with the “Radical Republicans” who wanted to use the full measure of federal power to safeguard the civil rights of ex-slaves and who thought it more sensible (and cheaper) to bribe Indians onto reservations rather than subdue them with force. Custer was a tempting political figurehead for the Democrats—-as a flashy Civil War hero, he was competitive in an electoral arena deafened by the Republican Party’s self-christening as the “party of Lincoln,” as savior of the Union, its waving of “the bloody shirt.” That Custer stayed in the Army year after year, subsisting on a small salary and content with unglamorous frontier postings though wealthy Democrats courted him so much, toasting him in New York City and whispering of wealth and power during covered carriage rides around Central Park, indicates the degree to which he had embraced his life on the Plains. Ambrose doesn’t stoop to the cheap gimmick of insinuating that Crazy Horse and Custer were the same man, but neither does he ignore the obvious appeal made to both men by the expansive freedom, the great gallopy distances of the Plains. George and Libbie rode together over the unfenced immensity for hours each day (the delusion of dashing cavalier romance they both inhabited may have been utter bullshit, but that doesn't mean it wasn't fun, or unsupported by reality: General Sheridan purchased the table on which Robert E. Lee signed the surrender terms and presented it to Libbie as a token of his recogniton of Custer's part in bringing the surrender about; and they were reunited in Jefferson Davis' bed at the Confederate White House, after the Union army entered Richmond). A born solider and sportsman, Custer clearly had a ball out there. It was real cavalry country that also happened to be richly stocked with exotic game. A leitmotif of the Custers’ voluminous connubial correspondence (eighty page letters were not unusual—-letters written by lantern-light, after a day in the saddle—-those Victorians!) is a promise extracted by his wife to stay with his of his men when on campaign. Custer and his staghounds would often light off in pursuit of the antelope and buffalo that encountered his line of march.

Custer had a well-deserved reputation as a martinet. Still, if he imposed a cruelly swift pace on his men when in the field, it was more because of an absorbed egoism—-he himself was a dynamo of energy whose need for rest and food was drowned out by the excitement of tracking an enemy in open country—-than a perverse desire to torture his men. One of Ambrose’s nice touches is his exploration of the degree of obedience Custer and Crazy Horse were empowered by their respective societies to demand. As commanding officer of a regiment of United States Cavalry, Custer was a lord over his men, and could impose, say, any killing pace he felt was called for. The nineteenth century United States Army in peacetime was about as feudal a governmental structure as existed in the nation, if you count out the Navy...for that nightmare, see White-Jacket, or The World in a Man-of-War (1850), by a US Navy deserter named Herman Melville. Ambrose mentions the grisly fact that during the Civil War, a high causality rate among his men was often taken to mean that a commander was real fighter; Custer lost more men, proportionally, than any other Union commander, but contrary to being thought a failure, he was, Ambrose writes, perhaps the most representative (and conspicuously rewarded) instance of the generalship ethos of the US Army at the end of the Civil War. Under Lincoln, Grant and Sherman that army was a fearsomely cold-blooded machine whose stated strategy was no more sophisticated than annihilation through attrition. The South would run out of men and material sooner than the Union, so keep up the pressure, bleed them white, whatever costs the Union forces incurred in men and equipment could be replaced by the north’s manpower surplus and massive industrial base. What I’m trying to say is that for officers like Custer who cut their teeth in the Civil War, a soldier’s life was cheap, and theirs to spend as they wished. This attitude was pronounced in the wartime army, when many of the soldiers were unprofessional volunteers, so imagine what it was like in relative peacetime, on the frontier, when the enlisted men, immigrants and ex-cons and misfit unemployables, had even less civic and social capital. Custer was authorized to demand so much, but his men were still human: before the Little Big Horn, the 7th Cavalry rode all day and all night of June 24, and then went into battle on the 25th without a wink of rest or a bite to eat, and Indian warriors later reported that after defensively dismounting for that Last Stand, many of Custer’s troopers were wobbly on their feet, and stumbling with fatigue.

Crazy Horse, Ambrose emphasizes, was the product of a society that awarded prestige rather than riches or authoritative command. Though a respected and much-followed war leader, Crazy Horse never had the official power to order his fellow warriors to, say, certain death, a power Custer took for granted. US Army troopers also performed an hour-and-half of drill every day when back at their forts (Custer the perfectionist probably demanded more—-it was said one always “knew the 7th by sight”); by contrast, when not actually fighting, the warriors who followed Crazy Horse often got bored and drifted away. The impetuous, individual, dueling, game-like character of Indian warfare was something Crazy Horse the innovative tactician was always butting up against. Crazy Horse did not always get young braves impatient for individual honor to perform the tactics he knew would bloody the Army, but when he did get them to fight in coordinated units—the Fetterman battle, certain incidents of the siege of Ft. Phil Kearny, the Little Bighorn—the results were devastating. The pervasive belief among whites like Custer that Indians weren’t their equals as soldiers may constitute a slur, but it becomes more understandable when one reads about Crazy Horse’s singularity as a commander. Custer acted foolishly, attacking with an exhausted and outnumbered (though not outgunned) compliment, but how was he to know a military genius was helping to direct the Sioux? I’m sure to Custer a two-pronged flanking attack on an encampment of people who weren’t likely to stand and fight seemed a sophisticated enough tactic. The elegance and patience Crazy Horse demonstrated in flanking Custer’s flanking attack were rare virtues among both Indian and white leaders. I think it right for Ambrose to maintain that the failure of Custer’s plan wasn’t a foregone conclusion; everything depended on his opponent’s reaction, and by that opponent Custer was simply out-generaled.

When Ambrose and Connell tell the same story, Connell is the more captivating narrator. But Ambrose tells quite a few stories Connell doesn't, goes into more depth about some things (Ambrose's chapter "Custer at West Point" is at points as funny as Lucky Jim), and besides Custer's strange personality emerges from any style of storytelling. An eccentric, Custer is at the same time profoundly representative of nineteenth century America, a fascinating gateway into the social and cultural making of Americans. I love his paradox: though in the murderous vanguard of America's settling of the continent, he was, for many important reasons (reckless individuality; career-long, almost reflexive insubordiantion; self-fashioning as an freebooting hunter-explorer, a type of selfhood, Ambrose writes, that white Americans owe to Indians), incapable of living in the settled society he was helping to extend:

Officers in the Indian-fighting Army after the Civil War were often heard to say that they much preferred the wild Indians to the tame ones, or that if they were Indians, they would most certainly be out with the hostiles, not drunk on the reservation. Custer expressed such sentiments frequently. These same officers took the lead in making certain that there were no more wild Indians.

As R.P. Blackmur pointed out, being mundanely out of step with the society around him doesn't keep a man from reflecting the wholeness of its contradictions.