New Orleans in 1918/1919: Jazz is on the rise, construction for the great industrial canal begins, and the city is terrorized by an ax murderer – all of these things really happened, and Nathaniel Rich mixes fact with fiction when he interweaves three narrative threads circling around those events.

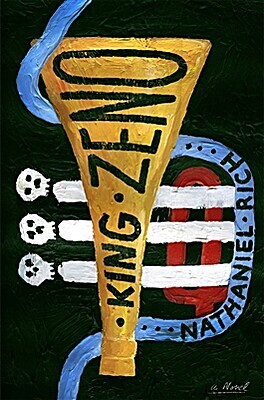

Isadore “King” Zeno is a struggling jazz musician who tries to break through as a cornet player while finding ways to provide for his family. While King Zeno is a fictional character, Rich mixes in a lot of historic references: In 1918/1919, there was indeed a particularly inventive cornet (and trumpet) player making a name for himself in New Orleans – Louis Armstrong. He played with other gifted jazz musicians like Kid Ory (the name of Zeno’s wife is Orly, and Kid Ory is also mentioned) and his idol King Oliver (who is also one of Zeno’s inspirations). Back then, Armstrong was married to his first wife Daisy Parker (Daisy is the name of Zeno’s mother-in-law). It is also correct that New Orleans jazz musicians at first mainly played in Storyville, the red light district, before more respected establishments became interested in booking them as their popularity rose.

The building of the canal is also a fascinating aspect of the story: This deep-water shipping canal connects the Mississippi to Lake Pontchartrain, and it first broke during Hurricane Betsy in 1965, and then again during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, thus flooding huge parts of the city. Rich tells the story of how the canal was built, inventing a female head of the building company who is involved in crime and corruption. He talks about the first predictions of what might happen if the canal breaks, and he finds powerful images for the plight of the black workers who dug at the construction site.

Most surprisingly, the “Axeman of New Orleans” was an actual serial killer who terrorized the city at the time, but while Rich fictionally resolves the case, the real axeman was never caught. I wanted to criticize Rich for connecting the threads of the story in the most implausible way, until I found out that the real axeman (or someone claiming to be the axeman) did in fact write the letter Rich tells us about, and unbelievably, it was published in a newspaper and did really say:

“I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have just mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it out on that specific Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.”

Until now, all of this sounds stellar, so as an alert reader, you might ask yourselves why I gave this book only three stars. While Rich manages to find some strong and haunting images, other parts are shaky and feel contrived. It is not elegant to let a person who is obviously dying declare “I am dying”, but it gets worse when this person declares multiple times that he is dying until he finally dies (and judging from what happened, he should have been dead long before that). Some characters, like the son of the construction company owner, remain one-dimensional and crude. Another example of a scene gone wrong would be when one of the policemen picks up his colleague, and then this happens:

“See I caught you eating pie.” He stuck a fat finger into the cream on Bill’s cheek and put it in his mouth. “I was shaving.”

He eats his colleague’s shaving cream? Or he would eat cream pie from his colleague’s face? No, people, he clearly wouldn’t. To add one last example, why is there randomly one singular sentence like this thrown in: “Lost in a daze, on a hazy crazy malaisy Friday.” Such playful choices made sense if Rich tried to transform jazz music into his language throughout the book, but he doesn’t.

These flaws are particularly sad because this novel has so much potential and could have been much stronger – In fact I blame the editor, not the author. An editor should have helped to manage the material and make the story and the language more consistent. Still, I can’t really hate on the text, because the story itself is great, the setting is great, and the narrative imagination that ties all threads together – logically, but also with slightly varying themes and poetic images - is also great.

This could have been absolutely amazing, but then it fell a little short. Still, I would love to read more by Nathaniel Rich.