What do you think?

Rate this book

416 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2008

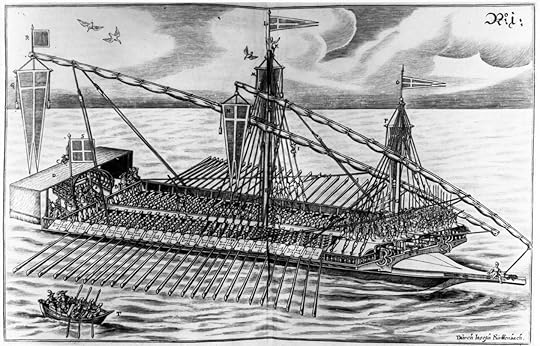

Period warship. 3–5 cannon in the bow, 1–2 in the stern; dozens of onboard naval infantry armed with period and medieval weaponry (swordmen, pikemen, arquebusiers, bowmen, crossbowmen); 20–30 banks of oars (port and starboard) with up to eight rowers per oar (hundreds of rowers); and auxiliary lateen sails.

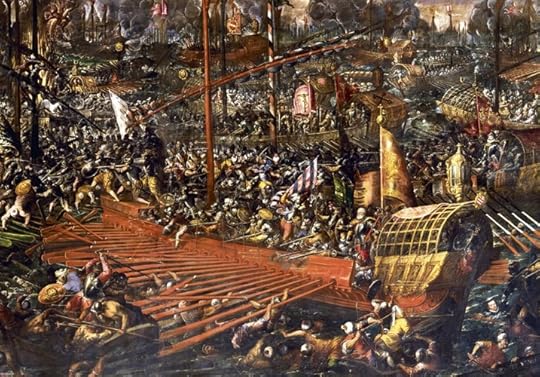

Period warship. 3–5 cannon in the bow, 1–2 in the stern; dozens of onboard naval infantry armed with period and medieval weaponry (swordmen, pikemen, arquebusiers, bowmen, crossbowmen); 20–30 banks of oars (port and starboard) with up to eight rowers per oar (hundreds of rowers); and auxiliary lateen sails.“... continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life ofCrowley wrote this book to describe the Ottoman Empire’s drive to control the Mediterranean—an Islamic form of Manifest Destiny. It grew from a long war of commerce raiding and slave-taking between Christians and Muslims starting from the Ottoman conquest of Byzantium and the collapse of the Crusader States. Most naval operations supported amphibious assaults to seize island bastions and coastal strongholds. These operations often devolved into months-long sieges. Siege warfare, in this late-medieval era, had changed little since antiquity except for the adoption of cannon and firearms and with the traditional medieval fortification giving way to the trace italienne , developed to resist artillery.mana galley slave was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” — (Paraphrasing) Thomas Hobbes

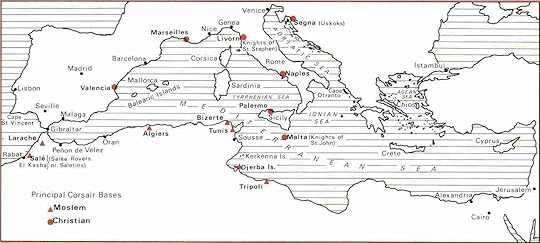

Mediterranean Corsair Strongholds, mid-1500s

Mediterranean Corsair Strongholds, mid-1500s