What do you think?

Rate this book

129 pages, Paperback

Published June 8, 2017

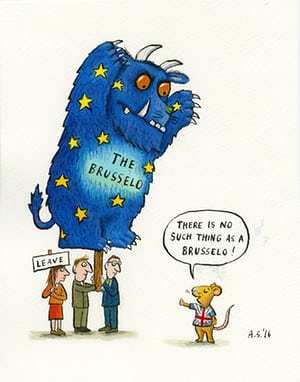

We, the undersigned, representing a range of literary arts and institutions, believe that Britain should remain within the EU. The In/Out debate often neglects arguments from culture. We maintain that an isolationist step away from Europe is a step away from our own heritage. It is a step towards an insular position antithetical to the open interchange of ideas and support that has defined European culture.even enlisting the help of the Gruffalo's illustrator:

I realized that I had been living in one part of a divided country. What fears – and what hopes – drove my fellow citizens to vote for brexit? I commissioned Anthony Cartwright to build a fictional bridge between the two Britains that opposed each other on referendum day.The author's own motivation he explained:

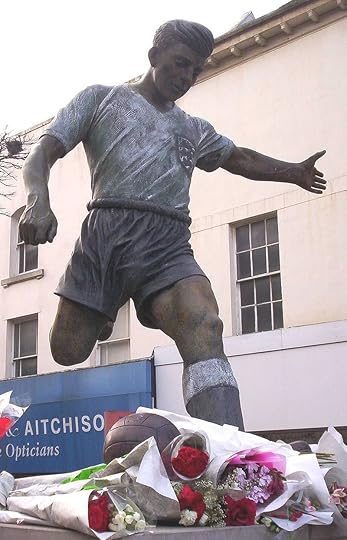

I wanted to write this book because, like many people, in the days after the referendum I felt angry. But I quickly realized that my anger was different. I was outraged at a reaction which labelled seventeen and a half million people “stupid” or “racist” or simply lacking (too poor, too old, too far away from london, too white). In the cut, I wanted to analyse the complex divisions undermining british society. We’ve been offered too many answers already, this is a story built on questionsThe Cut is set in Dudley, birthplace of Duncan Edwards, who statue features in the early pages,

She told her that her name was Ann, realised too late it was because she wanted to impress this woman, was ashamed of the way Stacey-Ann might sound to a woman like Grace. Realised the irony that she was sitting in the clinic, nineteen years old, with a baby on her lap, thrown out of her mother's house and no sign of the dad, so if anyone wanted to make judgements it wasn't her name she need worry about. And Grace gave her a card with her name on it and email and number, like that was the most natural thing in the world.However, too much was a little cliched for my taste - the Vote Leave sticker in the German car of the man wearing an Italian suit, the local UKIP branch that meet at the Indian restaurant, the colleague of Grace who spends most of his time in warzones but thinks Dudley is the biggest dump he's ever visited.

People are tired. Tired of clammed-up factory gates, but not even them any more, because look where they are working now, digging trenches to tat out the last of whatever metal was left. Tired of change, tired of the world passing by, tired of other people getting things that you and people like you had made for them, tired of being told you were no good, tired of being told that what you believed to be true was wrong, tired of being told to stop complaining, tired of being told what to eat, what to throw away, what to do and what not to do, what was right and wrong when you were always in the wrong.

“I doh think that feel like they’ve lost out. They have lost out”

“Isn’t that the same thing”

“No, thass part of the problem, thinking that it is. We’m sitting on one of the places we’ve lost [the old County Ground in Dudley, once a venue for Warwickshire matches]. You make out like it’s our problem, it’s only about how we feel. But we have los tit, it doh really matter what we feel about it. It’s a fact. You can prove it”

“What can you prove”

“The loss, actual jobs. Jobs, houses, security all them things … But maybe yome right that there’s feelings as well, of loss, of having lost”

”These people have got it coming,” he said with a feeling she found hard to understand. The man she had know for a few hours, less. She surprised herself when she noticed no wedding ring, not that it meant anything. They had talked so far of fathers and newspaper stories.

“Which people?”

“The people who write this crap.”

“It’s just a game to them, a funny game, like life’s a game. I bet the people writing these papers don’t vote to leave, I bet they live in fancy houses in London and they’ll vote to stay. They’m all doing fine, thank you very much. It’s like a double bluff.”

“Who’s playing games now?”

“You get what I mean, though?”

“I’m not sure I do. You mean that people here will vote against whatever they think the perceived elite will vote?”

“Here you go again. It ay perceived. There is an elite.”

“But some of the elite want you to vote to leave.”

“They doh mean it.”

“What do you mean, they don’t mean it?”

“I’ve told yer, it’s a game of double bluff. They’ll all argue about it. We’ll have the vote. It’ll be a vote to stay in. They’ll fix it if they need to. Then they’ll get on with whatever’s next on the agenda, all mates together again.”

“I think they mean it, and anyway, what, it’s all one big conspiracy?”

“You said it. A conspiracy of the elite, thass your word by the way, these are your own words, against the rest of us. You should write this down, put it in your film.”

“I will,” she said. She suddenly had to laugh.