Sometimes when reading a book my brain makes connections that other readers might not--not because I'm an especial genius but because we all have different sets of experiences that remind us of seemingly disparate things.

A day after finishing Donald Spoto's biography of Marlene Dietrich and fixating on the extent to which she created and maintained a public image and self-image--even having Jean Louis and other costume designers and makeup artists encase her body in a flesh-colored, foam-rubber fake body to suggest an ageless physique under her sleek stage costumes--I could not help but be reminded of Joris-Karl Huysmanns fin de sicle masterpiece, A Rebours (Against Nature), in which the male protagonist, Des Esseintes, secludes himself to create an environment of complete aesthetic artifice. Dietrich spent an entire lifetime doing that very thing to herself, creating an artificial image so inviolate that her own sense of reality and identity become submerged into it. Once Dietrich no longer felt able maintain the artificial image of eternal youth and sexuality, she withdrew from the world. It's as if Dietrich came to believe that her value as a person and her talent had evaporated once she felt unworthy of being seen.

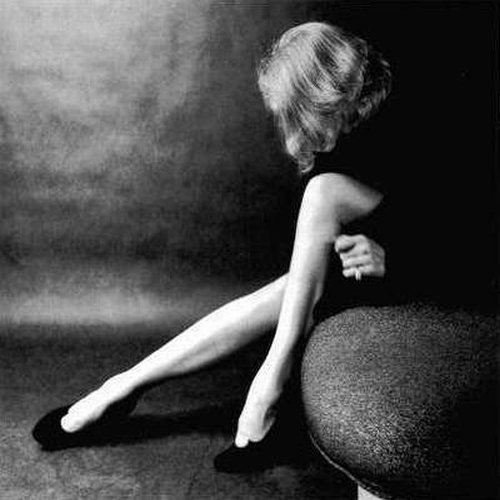

As the creator of an artificial image, Dietrich had it all over Lady Gaga and Madonna. Spoto's book is best when it examines how Dietrich sculpted that image, how it evolved and overtook whatever other identity she may have had. Dietrich was a force of nature, a woman of incredible discipline, and authority--steamrolling her way to fame and fortune often through sheer force of will and personality. Her singing and acting talents were limited; her legendary looks owed a great deal to creative lighting, camera angles and makeup. And for the rest of her showbiz career she often became her own director in order to sustain her "brand", telling her ostensible auteur bosses how she would be photographed and posed--or else.

In a small role, Dietrich had the most memorable line in Orson Welles' masterful 1958 movie, Touch of Evil when, in considering the checkered career of a friend-- a corrupt police detective (played by Welles) who was a hero to some and a pox on law enforcement to others--she coolly asks: "What can you say about a man? What does it matter what you say about people?"

Dietrich felt the same way about the facts when it came to herself; to her it was the fiction that mattered. This book asks: What can you say about Marlene Dietrich? Spoto, to his credit, stops short of telling us *who* Marlene Dietrich was, since in many ways she was as elusive as the blase characters who defined her screen image. All of us are contradictory and explicable, but because we don't exist in the celebrity fishbowl or attract massive attention to ourselves we somehow believe ourselves to be "normal" or average people. Dietrich was vain, sexually driven, struck by moments of humility and charity, etc.--in other words, she was what we all are, just on a grander scale.

She did manage to defy convention in ways that even today would perturb many of the insufferable prigs who'd like to make bedroom inspection mandatory for consenting adults (she was very much into casual sex with women and men, and pulled off the nearly impossible feat of remaining on friendly terms with most of her ex-lovers). She was fiercely independent in ways that earned both admiration and scorn. Dietrich's actions and motivations were contradictory, selfish and often childish. And just when you think you hate her, she does something marvelous and admirable. At the height of her beauty and popularity she was the world's most glamorous and highest-paid woman. At the same time, she loved being a traditional German hausfrau, cooking classic mittle Euro fare or scrubbing the floors for those she chose to dote over at any given moment. Dietrich's very Germanic obsession with cleanliness seemed to be another of her ways of maintaining the orderliness and artifice of her life, but also was a way of controlling others and, as Spoto suggests, was a kind of penance for some of the guilt she accumulated during her life for the casually cruel way she often treated friends and loved ones.

Along the way, there is plenty of name-dropping, and the bisexual star's bedroom partners included a gallery of lesser known women and famous men, including John Wayne, George Raft, Jean Gabin, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Erich Maria Remarque, Gary Cooper, Josef von Sternberg, John Gilbert, Clark Gable, Maurice Chevalier, Frank Sinatra, Kirk Douglas, Eddie Fisher, Mike Todd, Raf Vallone, Burt Bacharach and Yul Brynner. An affair also is alleged with General George Patton during Dietrich's admirably grueling USO stint during World War II, though at least one Patton biography I have on hand, by Stanley Hirshson, denies this.

There are some factual errors in the book, the worst being an attribution of the 1924 classic, The Last Laugh to director G.W. Pabst instead of to F.W. Murnau. For a star biographer and film expert of Spoto's calibre this seems an egregious rookie mistake. In another passage he seems to suggest that American howitzers destroyed the monastery and town of Cassino during the time Dietrich was entertaining troops in Italy. This is a woefully erroneous statement, as it was primarily bombers and a combination of weaponry that leveled the buildings.

Otherwise, Spoto has done good research, and tells us the facts of Dietrich's life, surmises about her motivations when the facts and circumstances warrant, and analyzes the films very well to show us the life-imitates-art parallels. It's a solid and very readable effort and answers probably all that I would want to know about the screen legend.