What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1984

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08kttjw

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08kttjw

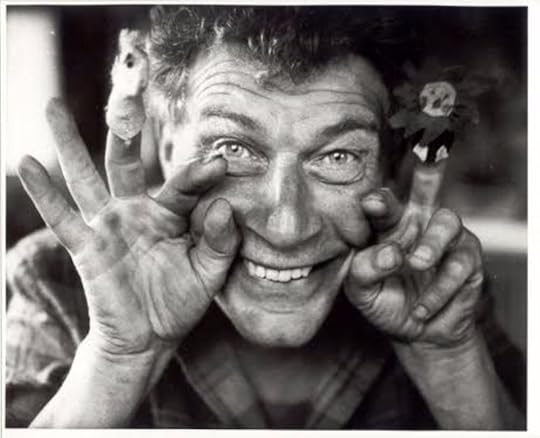

Today we meet Berger in his beloved Haute-Savoie mountains, as he crosses the frontier into Italy and begins a rumination on human conceptions of time, memory, poetry and art, specifically the paintings of Rembrandt.

Today we meet Berger in his beloved Haute-Savoie mountains, as he crosses the frontier into Italy and begins a rumination on human conceptions of time, memory, poetry and art, specifically the paintings of Rembrandt. Berger meditates on art, love and mortality - specifically how paintings depict time and how we understand the physical landscape around us, illustrated by sketches from the islands of Scotland and Berger's beloved Haute-Savoie mountains.

Berger meditates on art, love and mortality - specifically how paintings depict time and how we understand the physical landscape around us, illustrated by sketches from the islands of Scotland and Berger's beloved Haute-Savoie mountains. Berger explores the psychic impact of mass migration and how, once lost, the sense of a true home can rarely be regained.

Berger explores the psychic impact of mass migration and how, once lost, the sense of a true home can rarely be regained.  Berger considered the twentieth century "the century of banishment" and today he continues his exploration on the psychic impact of mass migration where for migrants home is no longer a dwelling place but the untold story of a life being lived.

Berger considered the twentieth century "the century of banishment" and today he continues his exploration on the psychic impact of mass migration where for migrants home is no longer a dwelling place but the untold story of a life being lived. Berger explores the work of his favourite painter, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Berger explores the work of his favourite painter, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio."The boon of language is not tenderness. All that it holds, it holds with exactitude and without pity, even a term of endearment; the word is impartial: the usage is all. The boon of language is that potentially it is complete, it has the potentiality of holding with words the totality of human experience—everything that has occurred and everything that may occur. It even allows space for the unspeakable. In this sense one can say of language that it is potentially the only human home, the only dwelling place that cannot be hostile to man." (95)That very last paragraph, though.

Perhaps it did not have to travel far; the distance between your voice and my ear was infinitesimal. But reality should never be confused with scale, it is only scale that has degrees.Or see his meditations on emigration, which are heavy with truth:

Emigration does not only involve leaving behind, crossing water, living among strangers, but, also, undoing the very meaning of the world and – at its most extreme – abandoning oneself to the unreal which is the absurd.Simple, clear, and movingly compassionate.

Emigration, when it is not enforced at gunpoint, may of course be prompted by hope as well as desperation. [...] The poverty of the village may appear more absurd than the crimes of the metropolis. To live and die amongst foreigners may seem less absurd than to live persecuted by one's fellow countrymen. All this can be true. But to emigrate is always to dismantle the centre of the world, and so to move into a lost, disoriented one of fragments.

‘—Lying on our backs, we look up at the night sky. This is where stories began, under the aegis of that multitude of stars which at night filch certitudes and sometimes return them as faith. Those who first invented and then named the constellations were storytellers. Tracing an imaginary line between a cluster of stars gave them an image and an identity. The stars threaded on that line were like events threaded on a narrative. Imagining the constellations did not of course change the stars, nor did it change the black emptiness that surrounds them. What changed was the way people read the night sky.’

‘Poetry makes language care because it renders everything intimate. This intimacy is the result of the poem’s labour, the result of the bringing-together-into-intimacy of every act and noun and event and perspective to which the poem refers. There is often nothing more substantial to place against the cruelty and indifference of the world than this caring.’

‘In reality we are always between two times: that of the body and that of consciousness. Hence the distinction made in all other cultures between body and soul. The soul is first, and above all, the locus of another time.’

‘Supposing that the universe is an expanding universe, its maximum diameter, the limit of its possible extension, has been calculated as being 25,000 million light years. One light year is 5.8784 × 1012 miles. Such an extension is beyond our imagination because of the terms in which it is expressed. There is a double separation: that of the statement and that of the numerical isolation. Elsewhere—in our hearts—we learn the proposition that the force by which space was created may have been an alternating force of expulsion and attraction, extension and passion. This is why, in every language, love is found quoting the stars. But it is also why every cosmology returns to sexuality. The “cosmic egg” of modern physics and the proposed single original substance of ylem—of which one cubic centimeter would weigh, 1,000,000,000,000 kg, and from which all other matter was born—are variants of a theme to be found in most creation myths. Only the nouns change.’

‘All theories about origin are either naive or despairing, from Genesis to Darwin. Yet perhaps one misunderstands their purpose. All origins are unattainable—just as, on a personal scale, it is impossible to imagine a self before conception. Theories of origin are attempts to explain our ongoing relation to the so-evident energy of the universe around us. The energy of our consciousness in all its concentration is continually trying to define itself by and against the energy of the universe in all its incomprehensible extension. Every form of interrogation of the stars has been about this, and every theory of origin is a story invented to describe the experience of being here. In the beginning was the creator. What followed—if there was to be any story at all—was deployment, extension, space, separateness. Ma femme.’

‘To break the silence of events, to speak of experience however bitter or lacerating, to put into words, is to discover the hope that these words may be heard, and that when heard, the events will be judged. This hope is of course at the origin of prayer, and prayer—as well as labor—was probably at the origin of speech itself. Of all uses of language, it is poetry that preserves most purely the memory of this origin.’

‘What reconciles me to my own death more than anything else is the image of a place—It is strange that this image of our proximity, concerning as it does mere phosphate of calcium, should bestow a sense of peace. Yet it does. With you I can imagine a place where to be phosphate of calcium is enough.’