"There was no point in trying to get him to say more. He had made his sacrifice to the Memory Monster."

Wow. I wasn’t prepared for this. I knew only the basics of the plot: a young Israeli man doing graduate work on the Holocaust is offered, by the director of Yad Vashem (the Israeli Holocaust museum), a job as a tour guide of the concentration camps in Poland. As the book opens, he has lost the job and is writing the director a letter trying to explain himself.

The book blew me away. Intellectually, emotionally, psychologically. There are many, many books about the horrors of the Shoah (the Hebrew term for the Holocaust), some realistic, others less so. As Dara Horn observed in her latest book, many of these works trivialize the horror, turning the Holocaust into some kind of morality tale. Others tell the story more realistically in graphic, shocking detail and leave the reader shaken, wondering How and Why it happened.

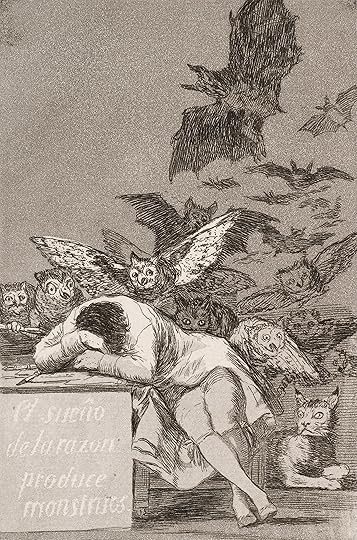

These same questions and details are in "The Memory Monster" too, but in a very different way. Not chronologically, but as the narrator describes the tours he gave -- what he talked about, what questions he asked and was asked, what he was feeling. How do I explain what “The Memory Monster” is? Think about what the Holocaust has become in our minds. Not in terms of what happened, who did what, and so on, but as a massive hole in the heart of the Western world, a dark vortex of meaning and meaninglessness. Think too of the many ways in which we've processed it, responded to it: With anger, sorrow, hatred, fear, disbelief. How it challenges our notions about human nature. Prompts us to clench our fists and say “Never Again." Makes us believe that God is dead or maybe never existed in the first place. Raises unsettling questions about Evil in the world. Compels us to think about what we would have done had we been alive back then. Would we have risked our lives, the lives of our loved ones, to save strangers?

Now put all these questions together but keeping mind that the narrator is Israeli (as is the author) and he's writing to an Israeli official, and you have a sense of what “The Memory Monster” is.

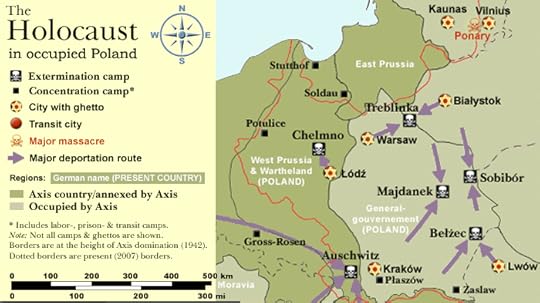

The tours the narrator gives are for Israeli high school students, members of the IDF, American tourists, and even Israeli ministers. He's very good at the job. He knows all the places, has memorized the names, can even identify faces in photographs from the time. The tours keep him away from his family for months at a time, but he is in high demand and this is how he earns his living. As he tells his tour group how the camps worked, we learn a lot of history but we are inside his head (or at least his letter) and our attention is drawn to him as teller of the story. Over the course of the book we watch him change, going from not-quite-detachment to something dark and volatile. He gets frustrated, impatient, angry, says things he shouldn’t, has moments when he believes he is himself a prisoner at Birkenau. He becomes consumed by his subject. His letter to the director, his words to the students -- taken as a whole, they bring up almost all the questions the Shoah evokes. Not in any analytical manner or as questions and answers, but as part of a narrative of self-report. Through him we hear what the students are thinking and saying, what teachers say to him during and after. What he feels as he describes the Selektions (where Jews are released from railroad cattle cars and sent left or right, to die at once or to die slowly) and looks up to see the students looking at their iPhones. Or when his lecture to a busload of American tourists about the special Nazi killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) is interrupted by one of them calling out to a friend, “Check it out, there’s an IKEA here.”

The complexities of our responses to the Holocaust are held before our eyes for inspection, often in a surprising manner. An example: For all that Nazis are in our minds the epitomes of Evil, the narrator observes that "it is hard for us to hate people like the Germans. Look at photos from the war. Let’s call a spade a spade: they looked totally cool in those uniforms, on their bikes, at ease, like male models on billboards.” He even does an experiment where he Photoshops the SS insignias from a picture of Reinhard Heydrich and has the students say what they think of this unidentified man. ("He's hot," he hears one girl say.) Later we learn that the Israeli officers he meets often feel the same way: "These officers had no hatred for the Germans either. In their speeches, the murderers had no image or language. They’d just dropped out of heaven." The narrator remarks, almost as an afterthought, “We’ll never forgive the Arabs for the way they look, with their stubble and their brown pants that go wide at the bottom.”

As a tour guide, we learn, he was instructed never to use demeaning phrases like ‘lambs to slaughter’ and he scrupulously adheres to the rule. More than once, though, he overhears students belittling these Jews because they “weren’t able to protect their wives and children, collaborated with the murderers, they weren’t real men, didn’t know how to hit back, cowards, softies, letting the Arabs have their way.” Incidents like this lead resonate with particular power today. Many people have asked why the victims didn't resist, but students saying this couch the question in particularly Israeli terms: as Mizrahi (i.e., Middle Eastern) vs Ashkenazi (East European) Jews, revealing a fissure in Israeli culture. More unsettling than this exchange is when one Israeli student remarks, “I think that in order to survive we need to be a little bit Nazi, too.”

A bit of chaos ensued. Not too much, though. He was just saying to adults what they usually only say among themselves. The teacher pretended to be shocked, waiting for me to respond, to do their dirty work for them, to take care of this monster that they and their parents had nurtured… “That we have to be able to kill mercilessly,” he said. “We don’t stand a chance if we’re too soft.” A few of them voiced some meek protest, nothing more. “But you’re not talking about killing innocent people,” the principal clarified. The boy thought for a moment, calculated, taking his time… Then he said, “Sometimes there’s no choice but to hurt civilians, too. It’s hard to distinguish civilians from terrorists. A boy who’s just a boy today could become a terrorist tomorrow. This is, after all, a war of survival. It’s us or them. We won’t let this happen to us again.” Can any reader see this exchange without feeling something, wondering what he or she might have said? Add to this the fact that, as the narrator tells us, the students commonly get together after the tour, wrap themselves in Israeli flags (as if they are prayer shawls), and recite prayers.

There's more to the book than the tours. The narrator, so widely respected for his breadth and depth of knowledge, is hired to advise a software company as they develop a program designed to give an accurate picture of what the camps looked like and how they operated. It is only after a few rounds of back and forth with the developers that he realizes the program is not a teaching tool but a game. (Such games do in fact exist.) Adding a further level to the questions raised by the book, author Yishai Sarid has the narrator try the game himself and then write about it in his letter to the head of Yad Vashem: “I played the part of a Jew, then of a German… The characters were almost three-dimensional. I had wondered if they’d sent you [i.e., the director] that version too, if you had also loaded corpses into the crematorium… I couldn’t stop—their game was so wonderfully terrible.”

Later he is retained by an Israeli ministry to help stage a mock “rescue” of the camp Jews: “…a combined IDF force would be landing in helicopters at the chosen site, deploying and in fact taking it over, followed by a ceremony, speeches, songs, the entire program.” What are we meant to make of this? Is a worthy testament to survival, to the empowerment of the Jewish people? Or perhaps the opposite, something trivial and a bit pathetic. (This particular kind of thing hasn't happened in the real world, but Israel fighter jets have done flyovers above the camps.)

I found the book most powerful when the narrator confronts us with the really big questions, like God and the Holocaust. (“God wasn’t there, of that I was sure, and if He was, then He was a shit God, our Shitty Father, a great big shit"). Or when he tries to explain to students why camp prisoners were willing to become Capos and Sonderkommandos. He explains "the animalistic urge to survive at any cost," adding that even Soviet soldiers who were taken as prisoner rarely rebelled. "I would have done the same,” I told them, “and you probably would have, too. We would have all carried bodies from the gas chambers to the crematorium, pulling gold teeth from their mouths, shearing their hair to feed it into the fire if it meant staying alive one more day.

He asks touring IDF officers: If you had been serving in the German military at the time, say in the armored corps or in airplane maintenance or in personnel management or in the electronic intelligence bunker, and your beloved homeland was at war with its enemies on all borders, would you have defected if you’d found out that somewhere far off, in the east, people were doing this kind of dirty work? I guess not. I know I wouldn’t.

Students too: “Who among you would have rescued a strange, filthy boy who knocked on your door at night, putting your own life and the lives of your children at risk?” I asked them in our nightly session at the hotel. Silence. Then whispering. Their brains ground through the options. How to get out of this? “He isn’t one of your people,” I reminded them. “He’s of a different faith. You don’t even know him. You have no obligation toward him, other than being humans.” A few raised their hands. “Would you die for him?” I persisted. “Would you risk having your home set on fire with you and your children inside?” At this point the hands usually came down. How does a reader see scenes like these without asking the same questions of himself?

“The Memory Monster” provides no answers because none exist, it just puts the questions before us and invites us to wrestle with them. Not in any pedantic or abstract way, but as a story about people trying in their own ways to process events that are ultimately incomprehensible. One other key thing about the book is so prominently before our eyes, it seems to me, that we're likely to see right past it: the book is in some way itself a tour, although instead of visiting the physical sites of the Holocaust we are being asked to examine the complicated mental landscape it occupies in our thoughts and memory. I found myself uncertain how I felt about the narrator at different points of the novel. Sometimes I felt empathy, at other times revulsion. I don't believe it's possible not to put oneself in the tour guide's place, even if only to reject his words. posing the questions obliges the reader to wrestle with them too, which puts him in a difficult place emotionally, morally. Really, I can't help but think this discomfort is exactly what the author was aiming for.