What do you think?

Rate this book

178 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1968

حيث كان يعطى للذين يتقدمون لامتحانات الدولة في الصين مطلع فقرة من فقرات كونفوشيوس، ويطلب إليهم الاستمرار في تلاوة البقية من الذاكرة. وذلك لأنهم في ذلك العصر أيضا كانوا يعتقدون ان التذكر أكثر أهمية من الفهم.

ولكن ما معنى تلك الأفضلية المعطاة للذاكرة؟

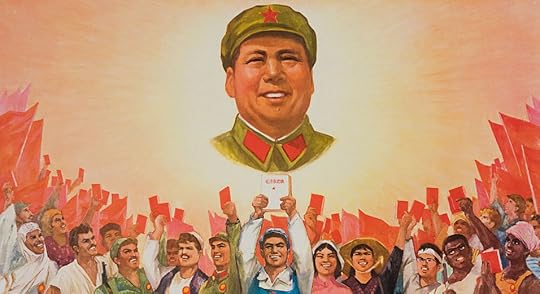

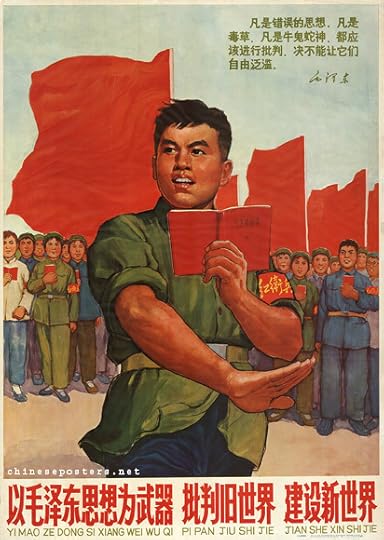

نستطيع ان نقول أن: الذاكرة تحفظ وتصون كل ما لا يستطيع ولاينبغي أن يكون موضوعا للنقد وبالتالي موضوعا للتغيير والتبديل، أو أنها عملية عقلية تضفي سلطانا على شيء لا يرغب المرء في أن يراه يفسد أو يتحطم وهي تقوم عندئذ بتحنيطه.