What do you think?

Rate this book

50 pages, Paperback

First published November 9, 1957

“I’ve seriously considered—I’ve very seriously thought about—throwing the whole thing up. This business of being a successful actor. What’s the point, if it doesn’t evolve into anything?”

This box set of the 50 books in the new Penguin Modern series celebrates the pioneering spirit of the Penguin Modern Classics list and its iconic authors. Including avant-garde essays, radical polemics, newly translated poetry and great fiction, here are brilliant and diverse voices from across the globe. Ground-breaking and original in their day, their words still have the power to move, challenge and inspire.

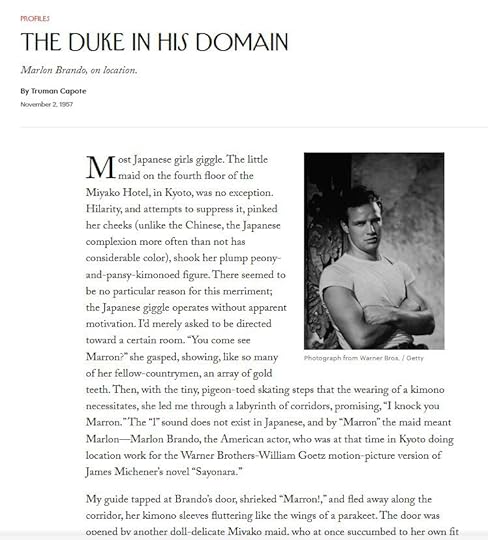

“Of course,” he said hesitantly, as if he were slowly turning over a coin to study the side that seemed to be shinier, “you can’t always be a failure. Not and survive. Van Gogh! There’s an example of what can happen when a person never receives any recognition.”The Duke in His Domain is a newspaper article published in 1957 in The New Yorker. In 1956, Truman visited the American film legend Marlon Brando in Kyoto, where he was just filming Sayonara. I knew next to nothing about Brando, apart from the fact that fucking Mike Pence named his pet rabbit after him (thank you, John Oliver!), but after reading Truman’s portrait of him I cannot help but be intrigued. If you look past all of their masculine bullshit and their fetishisation of Japanese culture and women (and believe me there’s a lot of that in here, so you kind of have to close both eyes, both ears and basically throw the whole book away…), you get some very genuine moments of tenderness and vulnerability.

“All right, you’re a success. At last you’re accepted, you’re welcome everywhere. But that’s it, that’s all there is to it, it doesn’t lead anywhere. You’re just sitting on a pile of candy gathering thick layers of—of crust.”Marlon Brando, judging by Truman’s take on him, seems to be quite the walking cliché. He’s a Hollywood beau who isn’t able to deal with his fame. He thinks that most of the movies he starred in are pointless and he feels like he’s wasting his life; he wants to produce something thoughtful and important, something that will bring peace to this world. Alrighty, good luck with that. He also had a tragic childhood, the whole “from rags to riches”-spiel, add an abusive father and a mother who chose alcohol over him to the mix, and you get the pciture. It’s all quite tragic, and Truman wants the reader to feel sorry for him. I personally couldn’t be bothered but it might have worked on his readers back in the day.

“I can’t. Love anyone. I can’t trust anyone enough to give myself to them. But I’m ready. I want it. And I may, I’m almost on the point, I’ve really got to . . .” His eyes narrowed, but his tone, far from being intense, was indifferent, dully objective, as though he were discussing some character in a play—a part he was weary of portraying yet was trapped in by contract.I know all of this is subjective but when I read the paragraph above and I cannot help but squeal a little bit. It’s that good.

It was then that I saw Brando. Sixty feet tall, with a head as huge as the greatest Buddha’s, there he was, in comic-paper colors, on a sign above a theatre that advertised “The Teahouse of the August Moon.” Rather Buddhalike, too, was his pose, for he was depicted in a squatting position, a serene smile on a face that glistened in the rain and the light of a street lamp. A deity, yes; but, more than that, really, just a young man sitting on a pile of candy.Oh Truman, you never fail to disappoint me.