There is a saying that goes: "Everyone is fighting a battle that you cannot see."

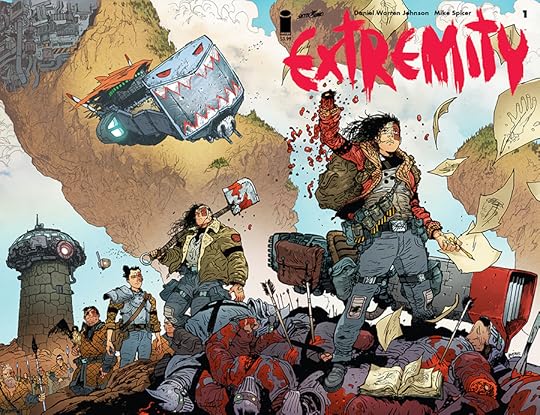

The anguish, the grief, and the heartbreak muzzled by those battles unseen tend to simmer and scar if left on their own. Whether in times of war or peace, conflict or bliss, the bane of a humanity whose awareness borders on the sacrosanct is its tendency to believe it (humanity) is (or deserves to be) better than human. EXTREMITY culls the pitiful ambitions of the downtrodden, and in the place of pity assembles a thirst for revenge so deeply mired that it is a wonder how any of these characters survive until the final panel.

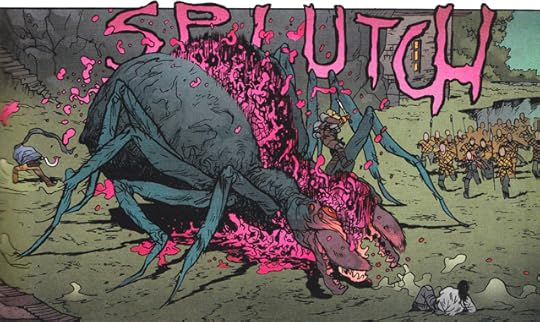

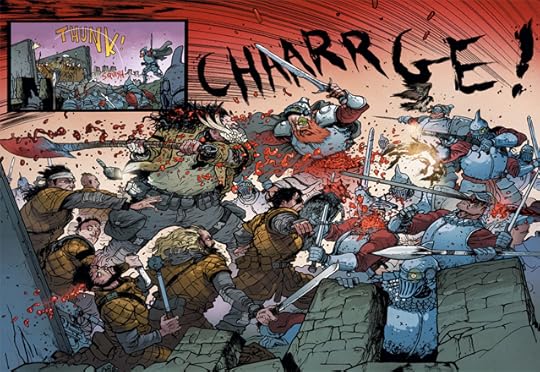

Thea of the Roto Clan is lost. Her father's war has pushed her and her brother, Rollo, to the outskirts. Does father care anymore? Is he so blinded by rage that his family no longer matters? With cannon balls sailing overhead, bloody swords salting the sullen earth, and the echoic cries of aged soldiers as they yearn for the warmth of their own families, long dead, Thea wonders of what use she, an "artist," can be in a world so thoroughly soaked, choked, and bewitched by blood.

Such is the way of EXTREMITY. Such are the internal conflicts of Thea, who endeavors to justify the hate she feels; of Rollo, who simply wants a friend; of Annora, Princess of the Paznina, who yearns for her mother's love; of Meshiba, a deserter-turned-protector-of-the-innocent . . . War and anguish darken the skies for these and other characters, but it's up to these characters, and no one else, to determine whether the sun has set for good or if it dares to rise and test its mettle one last time.

Daniel Warren Johnson has crafted an epic, this one already knows. But has he also crafted an epic with a heart questing to revoke the ties that bind humanity to its darkest inclinations? That's a tough story to write (and an even tougher story to write convincingly). And yet, the result is a comic book whose narrative rhythm, characterization, visual dynamism, and thematic consistency refuse to flinch in the face of mounting conflict. This is one amazing book.

It is, however, easy to feel bitter (or bittersweet) about a book like this. Very little occurs in a way one wants or expects for the characters. Thea's impatience and regret threaten to consume her compassion. Rollo's intellect threatens to consume and beguile his diligence. And then there's Meshiba, a big-bodied woman of color with a physical disability who steps up to lead a wayward people who have abandoned their tribal conflict. Meshiba is soft-spoken, easy-to-forgive, and noble; but only because she has already lived a life consumed with feverish pride (and discarded it). "Our way is not perfect," she says. "But we try."

EXTREMITY is a terrible storm on a beautiful beach, a disease of carrion on the hide of a newborn, the hammering of a rusted nail with a malformed fist.

There is only hope in the hope one carves for oneself.