"Tilli says, 'Men are nothing but sensual and they only want one thing.' And I say: 'Tilli, sometimes women too are sensual and want only that one thing.'"

A soufflé with a dash of hard liquor at its center, The Artificial Silk Girl is a sly, charming surprise; an undeservedly obscure, lesser-carat literary gem that is nonetheless priceless as a vivid peek into the lives of bohemian poverty and amoral decadence in Germany on the cusp of Hitler's dark age.

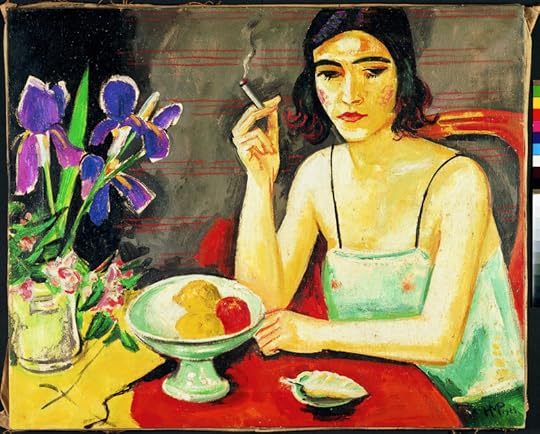

The protagonist of this odyssey is an arresting young woman, Doris, who has stolen a mink coat and gone off to Berlin with a vague notion of somehow becoming a star. Doris is vivacious and slightly ditzy, street smart and vacuous, sensitive and callous, materialistic and altruistic, and who, in everything she does, drinks in life like champagne.

She is a survivor, readily aware of the power of her charms. Men can't keep their hands off her, yet she uses that power to her advantage. After losing a steady office job in a law firm for rebuffing an amorous boss (whom she consciously plays like a fiddle), she lands a short-lived job as an extra at a theater, where she applies a devilish sense of human psychology and office politics to hilariously wreak havoc before leaving town with the hot mink on her shoulders.

Once in Berlin, she spends the last of her funds and turns to prostitution for sustenance, straddling the worlds of wealth and want. Rather than mope about her condition, Doris keeps an upbeat, dreamy outlook; dazzled by the lights, sounds, movement and possibilities of Germany's manic capital city. Berlin, for her, is one big party, and her approach is one of joie de vivre. She is the original polyamorous woman, adopting a philosophy of tit for tat; everyone wants something, and everyone transacts.

It's this attitude -- along with some explicit criticisms of the German domestic social order and marriage -- that undoubtedly got this book banned by the Nazis and its author ostracized. In fear for her life, Irmgard Keun went into hiding in Germany and elsewhere in Europe for the entirety of the war to avoid punishment. Fortunately, she survived, but was thereafter unproductive, and, sadly, refused all attempts by biographers to chronicle her amazing life until she died in 1982.

The book's style is deceptively simple, and I think deceptively is the operative word. Keun actually shows great sophistication in creating her portrait of a seemingly simple character and her naive dreams. Doris relates her tale in the first-person, ostensibly as a diary but also as material for an imagined screenplay about her life, a screenplay that will be in demand, once she is famous, of course. Doris' tale is told with staccato breathlessness, wrought as real stream-of-consciousness thought and real-time conversation; including interrupted and resumed thoughts.

One of the weird criticisms I've read about the book is that Doris is too shallow, or that her concerns are too slight to be of use to those interested in feminism or early feminist lit. But Keun is obviously smarter than her lead character. It requires great skill to "write down" to capture the voice of a girl simpler than the writer. And the book includes plenty of explicit and implicit criticisms of the patriarchy and its oft-fascist tendencies, as well as power issues in male-female relationships. Even though Doris complains about being nonpolitical throughout the book, it's clear that her everyday observations reveal the state of things and the seeds of fascism all around. Of course, Keun and her character were not third-wave feminists; expecting them to be is anachronistic and unreasonable. But Doris does represent a form of fledgling liberation, outsmarting men within the context of her limited options.

In its tone and its more surface concerns, The Artificial Silk Girl has been compared, somewhat accurately, to Sex and the City (and Doris, to Capote's Holly Golightly or Isherwood's Sally Bowles). Doris is a gal who flaunts her style and uses her wiles to survive, while seeking some kind of love or attaining some kind of goal while engaged in the flow of life. Doris mixes lovely little insights between frets about how her shoes and attire match her skin tone and hair color.

The most amazing section of the book, for me, occurs about halfway through the story, when Doris comforts an upstairs neighbor, a blind war veteran who is confined to a wheelchair and mistreated by his wife for being useless. The section is remarkable for two reasons:

1.) Up to this point in the story, Doris has not described herself physically in any clear way, though we know she is pretty and irresistible. Keun's strategy for rectifying this is ingenious. Doris is attracted to the neighbor, Herr Brenner, and allows him to stroke her silky legs while his wife is away. At the same time, Brenner asks Doris to describe herself. She starts out with a clinical description, assuming the theoretical position of a medical doctor; then, as she writes and her voice becomes more her own, her description morphs without apparent consciousness back into the first-person "I". It's bloody marvelous.

2.) Captivated by Doris' tales, Herr Brenner goads her, for page after page, to keep describing what she has seen and done in Berlin. At this point, Keun's Doris is given free reign to dish out a vivid, breathless, impressionistic kaleidoscope of Berlin nightlife. It's a beautiful passage that one could read over and over.

The only thing in the book that rang false for me pertains to some aspects of the translation. To capture the original spirit of a book and put it into proper context, it seems most correct to me to find words that serve as rough equivalents to words that would have been used in translations that would have been made at the time of publication. There are some points in the book -- not many, but enough to give me pause -- where some of the original German words have been translated into English words or phrases that seem too contemporary. At one point, for instance, Doris refers to being drunk as being "hammered," a term I think is of fairly recent origin. It's not enough to dismiss the book by a long shot, but is something to consider. There is an earlier English translation out there, somewhere, but it is not available for me to make the comparison.

Although I really think this is, at best, a four-star book, I'm rating it higher because it is in many ways a rare bird -- its voice and style are highly individual -- and because I think almost anyone can enjoy and appreciate it. It deserves to have a wider readership.

(KevinR@Ky 2016)

(*Post-review addendum:

I'm re-reading the second half of the book, and perhaps feeling less indecisive; I'm inclined to give this an unqualified five-star review).