What do you think?

Rate this book

752 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2012

I know quite well that, internationally, there is a very dark view of 6/4. The terrible images associated with it[1] have left a deep mark on public opinion. I also know that here, in China, those events caused great suffering. Lives were shattered, some even lost. [2] I know all that.I have quoted this in full to rip the bandage off the only festering sore in the entire work. Consider yourself now inoculated and free to proceed to enjoy the remaining 690 pages, where you will find first-person storytelling taking precedence over direct address to show-and-tell rather than whitewash-and-sidestep China’s remarkable, painful, prideful recent history. (To engage with those who think I doth protest too much, I claim there’s not a single sentence in the above lengthy passage that doesn’t have something glaringly wrong about it – I have marked 10, and hidden my objections under the spoiler box.)

But the truth is, like almost all my countrymen, my mind is occupied with so many other things I find even more important.[3] Partly because all that happened twenty years ago, and I have a habit of putting behind me parts of the past that are liable to make me uncomfortable.[4] Also because I didn’t personally suffer as a result… and partly because I’m convinced that, above all, China needs order and stability to develop. The rest is secondary, in my view.[5]

I know that might seem shocking, especially to Westerners, whose primary discourse is fundamentally different. This isn’t just me taking up some official line on my own.[6] No -- it’s a deeply rooted feeling many Chinese share, I think.[7] A feeling forged in elementary school,[8] where we learned of all the hardships and humiliations our country has had to suffer throughout the 20th Century: invasion, plunder, “unequal treaties,” internal divisions, battles among warlords. A feeling that has only grown stronger as, over the years, I lived history myself: the Cultural Revolution, which I remember so clearly… all my fellow countrymen who, year after year, fled their homeland.[9]

Those who know or can understand our misfortune must also be able to understand my profound desire for order and stability, in which I await our growth and rebirth. That said, everyone’s entitled to an opinion. Some might, for instance, object that human rights come before the need to develop. I’ll leave that debate to the generations to come -- those who won’t have known the indescribable torments we suffered for far too long. [10] (pp. 488-9)

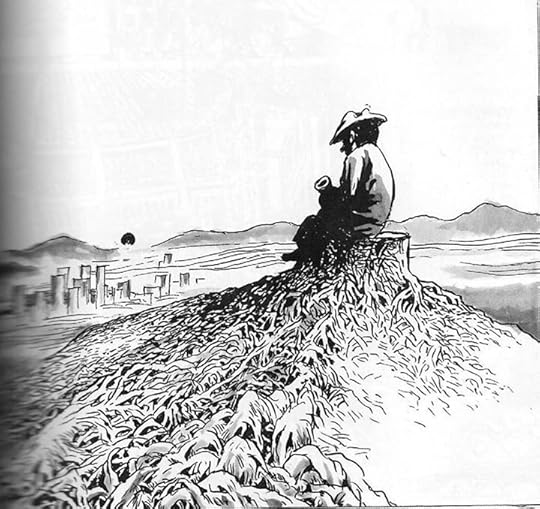

This image could be read as repentance given that at its first appearance on page 131, Kunwu is reflecting on his own destructive part in the Cultural Revolution: “Like many others, I try not to look back too often, to let memory tug me down the slope of remorse. But in truth, he who once, with the insouciance of youth, destroyed so many wonders would give so much today to find just a few of those marvelous objects intact, bearers of our history…” Yeah, well, we all have our regrets.

This image could be read as repentance given that at its first appearance on page 131, Kunwu is reflecting on his own destructive part in the Cultural Revolution: “Like many others, I try not to look back too often, to let memory tug me down the slope of remorse. But in truth, he who once, with the insouciance of youth, destroyed so many wonders would give so much today to find just a few of those marvelous objects intact, bearers of our history…” Yeah, well, we all have our regrets.

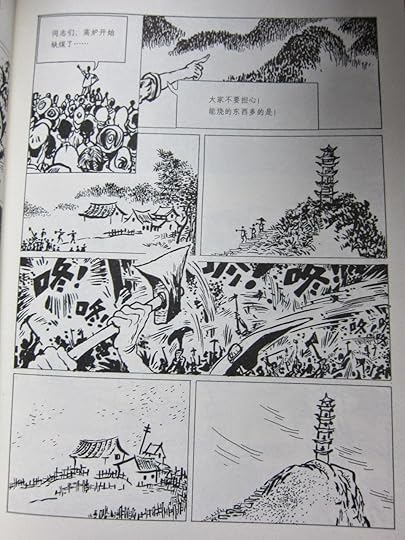

The Question and the Answer of the BirdHmmm. Maybe it was better in the original Mandarin? Maybe not. “Lots of us are wondering if he hasn’t lost his marbles!” is the reaction of one comrade (quickly shushed). Yet whether a moment of public clarity or senility, Zedong would be dead within the year. Likewise, the oppressive Cultural Revolution would end shortly after a coup led to the arrest of Mao’s wife (Jiang Qing) and three others for perpetrating the madness. Whether the Gang of Four were scapegoats needed to justify a sea-change in state policy sans apology or legitimately to blame, the impact was immediate and dramatic with loved ones reunited, burgeoning paranoia relaxed, and all of China breathing an enormous sigh of relief. (I’m guessing the Gang bore some legitimate culpability; it takes serious gumption to take on the widow of your holy founder – Jiang Qing could not have been all that beloved.)

The Roc, soaring ninety thousand li,

The blue sky on his back,

His gaze sweeping the ground.

There’s still plenty to eat,

Potatoes piping hot,

We’re adding the beef just now.

No point farting!

The party had previously promised its constituents an “iron bowl,” guaranteed employment and housing. You went where you were sent, a system which traded productivity and free will for security and stability. The new regime they called the “clay bowl,” and there were presumably many who looked on with more than a little anxiety that they would be left behind.

The party had previously promised its constituents an “iron bowl,” guaranteed employment and housing. You went where you were sent, a system which traded productivity and free will for security and stability. The new regime they called the “clay bowl,” and there were presumably many who looked on with more than a little anxiety that they would be left behind.