What do you think?

Rate this book

304 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2017

در پایان هر سه سال، تمامی دهیکِ محصول آن سالِ خود را بیاورید و در شهرهایتان ذخیره کنید، تا لاویان که آنان را چون شما نصیب و میراثی [از زمین کنعان] نیست، و غریبان و یتیمان و بیوه زنانی که در شهرهای شمایند، بیایند و بخورند و سیر شوند.

تثنیه ۱۴: ۲۸-۲۹

جمع کلّ لاویان سرشماری شده که موسی آنان را به فرمان یهوه برحسب قبایل شمرد، رقم ذکور از سنّ یک ماه به بالا، ۲۲هزار تن بود.

اعداد ۳: ۳۹

دختر فرعون او را به فرزندی گرفت، و وی را موسی نامید چرا که میگفت «او را از آب برگرفتم».

خروج ۲: ۹

قوم خود را خواهی آورد و بر کوه میراث خود مستقر خواهی کرد

مکانی که، ای یهوه، که آن را مسکن خود ساختی

مَقدِسی که، ای خداوند، دستانت ساخته است.

خروج ۱۵: ۱۷

در باب لاوی گفت:

پس از آن که او را در مسّه آزمودی

و در آبهای مریبه با او مجادله کردی...

تثنیه ۳۳: ۸

یهوه از سینا آمد

و از سِعیر بر آنان طلوع فرمود.

او از کوه فاران درخشید.

و از نزد کرورهای قُدسیان آمد.

تثنیه ۳۳: ۲

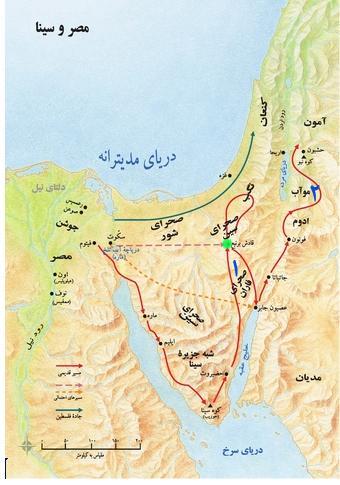

•Israelites would not have motive to say they were descended from slaves.From the above Friedman concludes that the exodus involved a small number, and that this group were what became the Levite tribe. In the writing of their stories there was an introduction and merger of Yahweh with El, and that merger was a crucial step in the formation of monotheism.

• There’s no motive to not be indigenous residents of their land.

• Levite priests have Egyptian names.

• Moses is an Egyptian name.

• Father-in-law of Moses was a Midianite priest.

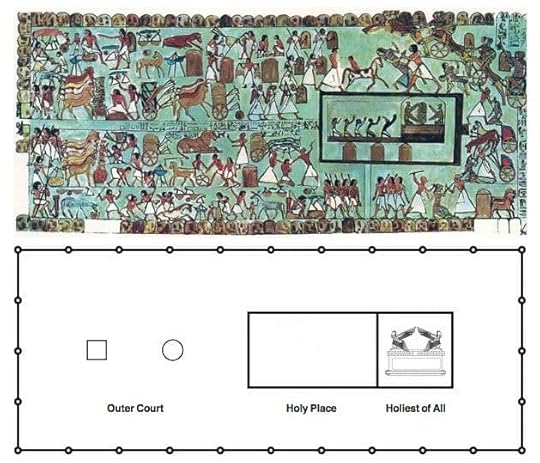

• Architectural match between Israeli Tabernacle with the battle tent of Rameses II.

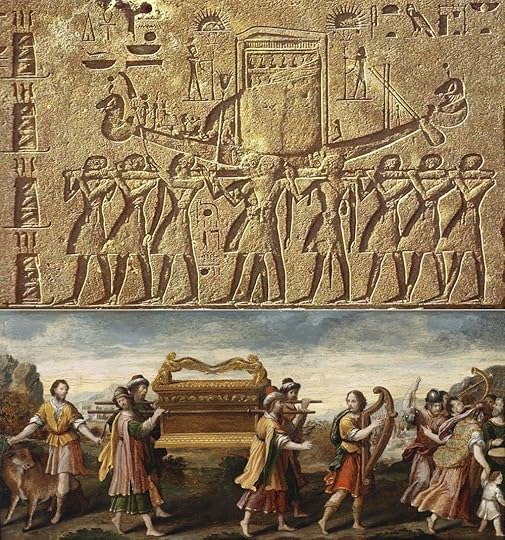

• Arch of the Covenant and the Egyptian bark are similar in design.

• Circumcision was an Egyptian practice.

• Circumcision is mentioned only in the E, P, and D (Levite) sources.

• 52 references to being good to aliens in the Pentateuch.

• Over 200 references in Pentateuch of “because we were aliens in Egypt.”

• Historical evidence of four hundred years of the presence of Western Semites as aliens in Egypt.

• E and P sources indicate God’s name is unknown prior to exodus story.

The idea of monotheism may have been in the air in Egypt after the demise of Pharaoh Akhenaten's religion of Aten. The majority of Egypt's population may have rejected that idea. A minority may have been attracted to it. The Levite community that left Egypt may have been led by an Egyptian man Moses, who was attracted to that one-God idea, and when they arrived at Midian he married a priest's daughter and learned of the god Yahweh, whom he identified as the one God. Or the Levites may have left Egypt and then met a Midianite man, Moses, and were attracted to identify his God Yahweh as the one God. Or maybe Moses and/or the Levites found the idea of one God on their own, and they were then influenced either by the Egyptian monotheism in the air or by the Midianite faith of Yahweh. We can arrange these puzzle pieces in a number of possible ways. The bottom line, though, one way or another, is that the Levites had spent time in both Egypt and Midian, their God was Yahweh, and then they came to Israel.Concluding chapters of the book address some textual issues such as those indicating that El had a female consort at one time, that earlier gods needed to die, and that God sometimes speaks in plural. The book also contains some textual exegesis defending the ethical concept that, "Love your Neighbor," applies to strangers, not just other Jews.