What do you think?

Rate this book

389 pages, Kindle Edition

First published October 3, 2017

Ella stared west. She imagined the great mountains foggy and raindamp in the distance, the blue ridges rolling away in great swells. She opened her mouth, paused for a moment, gathered the story of her life around her as she would lift the hem of a long dress before stepping across a stream. She did not think, did not stop to look at [anyone]. She simply began to speak.Events and people have a way of disappearing when they do not suit the narrative favored by those who decide what is to be allowed into our history books. Unless there are powerful interests taking on the task of sustaining that history it can fade from our consciousness. For myself, it took until college for me to have any but the most primitive clue about the labor movement in the United States, who the players were, what it had achieved, and its relevance to my life. Wiley Cash grew up in Gastonia, North Carolina, and had an awareness of his familial history in the area, but it was not until he was an adult that he learned of one historical event in particular. The idea for the The Last Ballad

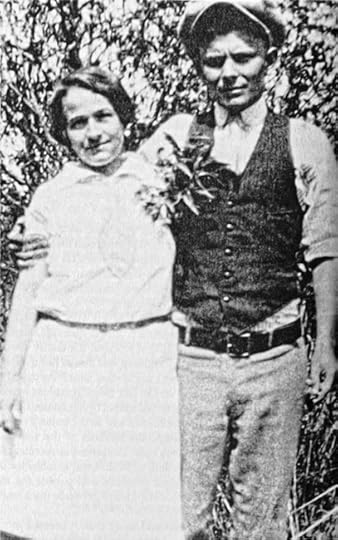

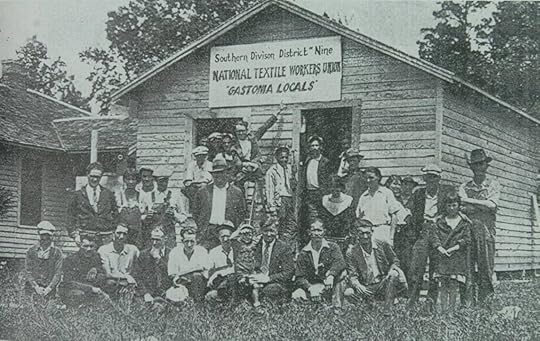

first started cooking in 2003 when I was in graduate school in Louisiana. I had never heard of the Loray Mill Strike. I asked my parents about it, and they’d never heard of it either. My mom was born in Gastonia in a mill village in 1945, and my dad in 1943, in a mill village in Shelby, and my mom’s maiden name is Wiggins. All my family came from mill people. My mom’s dad, Harry Eugene Wiggins, was living in Enoree (S.C.) in 1929 when Ella May was murdered. He would’ve known about it. But I never heard the word Loray. This story was buried. Nobody talked about it.Cash has brought it back into the light.

Women were beaten. Soldiers pressed guns to men’s heads. The strikers’ first headquarters had been destroyed by a nighttime mob. The union commissary attacked, the food stores ruined.The union tried to gain support from workers in other area mills, offering to transport folks to a planned rally. Ella had seen their leaflets, the union demands, and decided to attend.

Woody Guthrie considered her one of our nation’s best songwriters. Alan Lomax published her stark union ballads in his acclaimed collections of American folksongs. Pete Seeger recorded a version of her most famous song on a Cold War folk revival album. …Ella May Wiggins… is not well known today, [but] she was one of a handful of southern grassroots composers who combined traditional balladry with leftwing politics to forge a remarkable new song genre just prior to and during the upheaval of the Great Depression. - from the Southern Culture articleHer boyfriend even suggests she quit working at the mill and make a career out of music. But we are shown very little of this prior accomplishment. It is mostly by reference. The song she sings at the rally is what would be considered her greatest hit, The Mill Mother’s Lament, also sometimes seen as The Mother’s Lament. I included in EXTRA STUFF links to a couple of performances by other artists. There are no recordings to be had of Ella May performing her songs.

After her death, pressure from local strikers, North Carolina liberals, and national political organizations led Gaston County mill owners to reduce working hours to fifty-five per week, to improve conditions in the mills, and to extend welfare work in the textile villages. - from NCPEdiaThe Last Ballad is Wiley Cash’s strongest novel to date. He offers us insight into an important, if mostly forgotten, event in American history, a time, sadly, that has much in common with the world of the early twenty-first century. We could use more Ella Mays today. We could use more union organizing. With the nomination of an ultra-conservative senatorial candidate in Alabama, and the steady withdrawal from public life of the saner elected Republican officials, the rise of the Steve Bannons and Tea Party sorts in this country, the need to battle for labor rights has rarely been greater.

We leave our homes in the morning,

We kiss our children good-bye,

While we slave for the bosses,

Our children scream and cry.

And when we draw our money,

Our grocery bills to pay,

Not a cent to spend for clothing,

Not a cent to lay away…

And on that very evening

Our little son will say:

"I need some shoes, Mother,

And so does Sister May."

How it grieves the heart of a mother,

You everyone must know.

But we can't buy for our children,

Our wages are too low.

It is for our little children,

That seem to us so dear,

But for us nor them, dear workers,

The bosses do not care.

But understand, all workers,

Our union they do fear.

Let’s stand together, workers,

And have a union here.

this was another fabulous Traveling Sisters read with Dana, Jan, Nikki, Marie Alyce, Brenda, Lindsay, Jennifer, and NOrMA. Love how everyone brought their own personal experiences to the discussion... some of the sisters are a bit over scheduled, so I am looking forward to their thoughts! As always a pleasure to read with these ladies!