What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2005

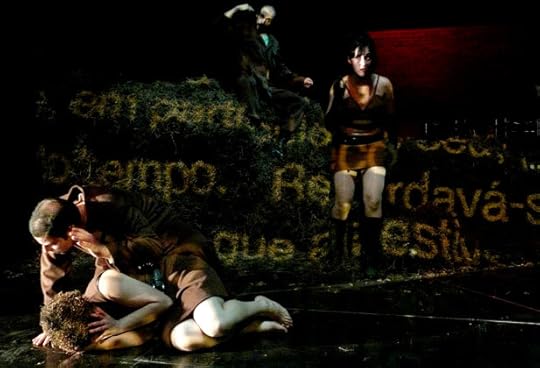

Cómo cantar un cántico del Señor en tierra extraña.Muchos de ustedes serán conscientes de que la Biblia es como el refranero, cualquier cosa que se quiera hacer o pensar en ella encontrarán una frase que la respalde. Es más, los mismos versículos pueden significar una cosa o su contraria dependiendo de quién los interprete. Justamente es lo que ocurre con este Salmo cuyo significado no puede ser más cristalino para mí, y creo que también lo es para dos de los personajes de la novela que toman el verso subrayado como una especie de mantra en sus vidas: el salmo es una exhortación para no olvidar nunca los crímenes de los que se ha sido víctima y un reclamo de venganza. O, dicho de otro modo, exhorta a las víctimas a no renunciar a ser verdugos. Así, el horror se combatiría con horror.

¡Si me olvido de ti, Jerusalén, que se me seque la mano derecha!

¡Que se me pegue la lengua al paladar si no me acuerdo de ti,

si no pongo a Jerusalén en la cumbre de mis alegrías!

Señor, toma cuenta de nuestros enemigos

cuando decían de Jerusalén: ¡Arrasadla hasta sus cimientos!

¡Capital de Babilonia, criminal,

quién pudiera pagarte los males que nos has hecho,

quién pudiera estrellar tus hijos contra las piedras!

“Un pueblo débil, es decir «sin posibilidad de poner en situación de peligro a un ejército invasor», no debería considerarse «un pueblo bondadoso», pues los hechos no se debían a una cuestión de bondad por un lado, el de las víctimas, y de maldad por el otro, el de los verdugos o los que ejecutaban el terror. Se trataba sencillamente de una cuestión de posibilidad y no de voluntad o deseo. Un pueblo débil respecto de otro podía pasar rápidamente —es decir, en términos históricos, en menos de un siglo— a ser un pueblo fuerte por haberse fortalecido durante ese periodo de tiempo o, sencillamente, por haberse acercado a un pueblo todavía más débil.”Si el horror es una consecuencia forzosa del enfrentamiento entre fortaleza y debilidad no hay responsabilidad ni culpa y, por tanto, no ha lugar para la venganza. El equilibrio de horrores se restablecerá en cuanto cambien las fortalezas relativas de los pueblos.

Hinnerk lived in constant fear of his fellow men- and yet, how many times, when he passed them on the street, had people said (and so casually... as though reciting their address or giving directions): look at that one, he has the face of a killer.

Hinnerk lowered his head so he wouldn't hear.