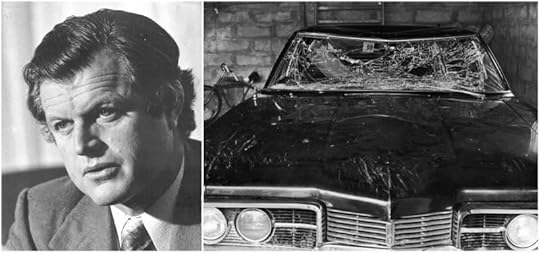

This book's original title, "Senatorial Privilege," better conveys Damore's basic thesis about Chappaquiddick: Ted Kennedy got away with manslaughter by being a Kennedy. His account is thorough, disturbing, and overflowing with passionate indignation. It's hard not to find Damore's anger infectious.

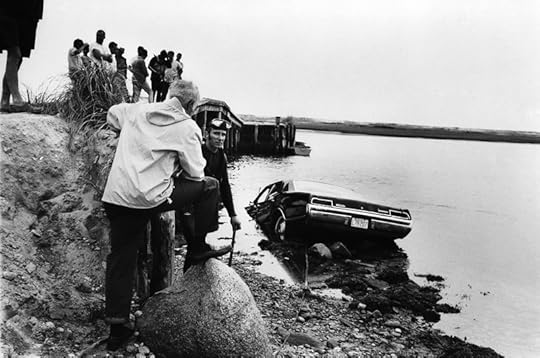

The most damning thing here is probably the timeline. Kennedy says he left the party at 11:15pm with Mary Jo Kopechne in order to take her back to the hotel by ferry. But Mary Jo hadn't told the other Boiler Room Girls at the party-- who shared her hotel room-- that she was leaving, nor did she bring her purse or room key. Implicitly, Kennedy's whole story hinges on the crucial fact that the ferry stopped running at 12am; if the incident happened later than that, he didn't have any (non-scandalous) justification for driving around at night with a beautiful young woman who wasn't his wife. But at 12:40am, a deputy in a marked car saw Kennedy's Oldsmobile driving down a dirt road to a cemetery with a male driver and a female passenger. The deputy approached the sedan, but the Oldsmobile raced away toward Dike Bridge (where it was later found flipped and submerged in the water, with Mary Jo's body inside). There's good reason, meticulously reconstructed here, to believe that Kennedy was drunk when he fled from the deputy. Regardless, the deputy's testimony puts the car's submersion at about 12:45am. Kennedy returned to the party on foot after the crash. Gargan, Kennedy, and Paul Markham went to the scene and unsuccessfully tried to get Mary Jo from the car (they couldn't because the tides were strong at that time). According to Joe Gargan's inquest testimony, they tried for 45 minutes, stopping after 2am. By 2:30am, Kennedy was back at the hotel in dry clothes, arguably trying to set up an alibi.

Damore ruthlessly exposes the inconsistencies in Kennedy's account(s), but he doesn't speculate too much about what Kennedy and Mary Jo might have been up to if not trying to make the ferry. He's respectful of Mary Jo and spends significant time trying to establish that-- whatever happened that night-- she was more than just a "secretary" or an unmarried blond who wasn't wearing underwear (as many reports seem to summarize her). He even includes comments from her parents about how "an examination" showed she was "a maiden lady." (Why your parents would have such an examination done on you in your late 20s is another question.) He's fairly easy on the secondary characters, too, particularly Gargan and Markham. Both knew about Mary Jo's death before the police, but didn't call anyone because Kennedy promised he would take care of it himself-- an omission that has resulted in much criticism against them personally. Still, Damore obviously believes that the car's submersion created an air bubble in which Mary Jo lived for some time, and he presents quite a bit of convincing evidence that she could've been saved if help had been timely sought; she had time after the crash to crawl into the back seat of the car and adopt a pose consistent with trying to breathe the last from a diminishing pocket of air, and she died of drowning rather than any impact injuries. The diver who ultimately retrieved her body did so in mere minutes, and has always insisted that he could've saved her if he'd been called right away. As it was, Kennedy didn't report the crash until the next morning, after it had already been discovered. (Again, Damore offers some damning evidence that Kennedy intended to blame Mary Jo for the crash by pretending he hadn't been in the car, or that he hoped Gargan or someone else might take the blame for him.)

It's clear that Damore had access to many witnesses close to the case, including Gargan, and he exposes angles that appear to have been new at the time of publishing (for example, that Kennedy had a mole in the DA's office and knew all the inquest questions in advance). It might be fair to say that Damore's anger here stems more from Kennedy's crass arm-twisting and (largely successful) attempts to thwart the criminal-justice system than from his initial conduct. As we read, e.g., that Kennedy paid for the Boiler Room Girls' attorney, who in turn constructed the girls' inquest testimony to corroborate Kennedy's and each other's to the point of unbelievability, that frustration makes sense.

The book closes with a brief analysis of Chappaquiddick's effect on Kennedy's political career. Damore concludes, I think with the majority of commentators, that it was catastrophic to his presidential aspirations. That didn't interest me as much as the legal/criminal aspects of the case, but it seems to have been Damore's way of softening the blow of his thesis-- a way of saying that Kennedy suffered some repercussions, even if he evaded a manslaughter conviction. It's easy to see why this book caused such a sensation in 1988, when it first came out. Even now, it contains a lot of information about the incident that I'd never heard before and found shocking. (Not that I considered myself an expert, by any means; I had a skimmed-the-Wikipedia-article level of knowledge prior to reading this.) It shows a little more authorial emotion than I typically like in my nonfiction, but it's certainly a fast and interesting read.