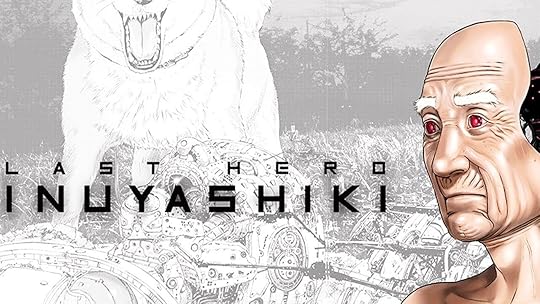

Inuyashiki by Hiroya Oku: A Flawed Yet Thought-Provoking Sci-Fi Parable

Inuyashiki is a bold and often unsettling manga that sees Hiroya Oku grappling with questions of mortality, empathy, and the digital age through the lens of science fiction. Serialized in Evening magazine between 2014 and 2017 and collected in ten volumes, the series presents a story that is at once intimate and grandiose, contemplative and violent. It has moments of brilliance but is also hampered by structural inconsistencies and tonal dissonance that keep it from reaching its full potential.

The story begins with Ichirō Inuyashiki, a 58-year-old salaryman who is socially invisible, disrespected by his family, and recently diagnosed with terminal cancer. His life changes when he is accidentally killed and resurrected by an alien force, which replaces his body with a powerful cyborg construct. In parallel, a teenage boy, Hiro Shishigami, is also transformed by the same event—but while Ichirō uses his powers to save lives, Hiro becomes a mass-murdering nihilist who treats humans as disposable. The series then follows their diverging paths, setting up an ideological conflict between selfless humanity and sociopathic detachment.

Oku's central conceit—a moral polarity between two newly empowered beings—offers a fertile ground for philosophical reflection. Ichirō’s struggle is moving and sincere. Despite his superhuman abilities, his compassion and pain feel real. Watching him use his powers to stop crimes and comfort victims lends the story its emotional anchor. Hiro, by contrast, is deeply disturbing. His acts of violence—cold, methodical, and often directed at innocent families—are graphic and hard to digest, yet they provoke urgent questions about isolation, emotional numbness, and unchecked resentment in youth.

The manga is visually strong, consistent with Oku’s signature style. He continues to use digital models for background design, lending the world a grounded, hyper-realistic texture that contrasts effectively with the fantastical events playing out in the foreground. Action scenes are kinetic and brutal, and emotional beats are amplified by expressive character work and dramatic framing.

That said, Inuyashiki suffers from tonal inconsistency. The early volumes succeed in cultivating a slow, reflective mood, but the pacing becomes erratic in the second half, with increasingly implausible plot escalations and a somewhat rushed conclusion. Hiro’s motivations—while intriguing in early chapters—never fully crystallize into a coherent psychological arc. The narrative occasionally flirts with social commentary, especially regarding media spectacle, generational apathy, and urban alienation, but these threads are often abandoned or left underexplored.

Oku also has a tendency to insert juvenile or exploitative elements—some sexualized imagery and a few adolescent gags—that clash with the otherwise mature and somber themes. While this may be part of his authorial voice, in Inuyashiki it detracts from the emotional weight of the story and undercuts its more serious philosophical ambitions.

In conclusion, Inuyashiki is a fascinating but uneven work. Its premise is powerful, its execution visually striking, and its core characters—particularly Ichirō—are handled with emotional sensitivity. But the series is held back by narrative unevenness, tonal shifts, and a reliance on shock that feels gratuitous at times. For readers who appreciate dark science fiction with moral complexity and high-concept premises, Inuyashiki remains worth reading—just don’t expect it to maintain the same focus or emotional resonance throughout.