What do you think?

Rate this book

296 pages, Kindle Edition

Published January 30, 2018

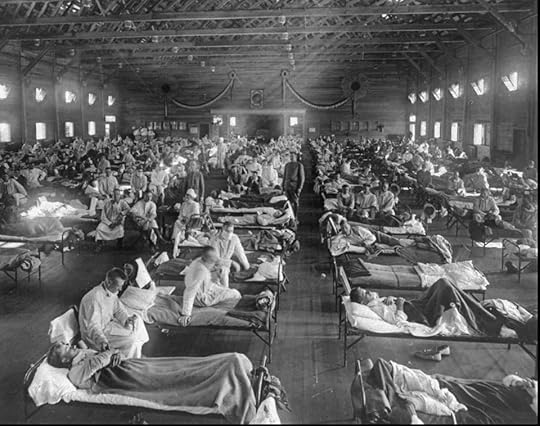

What frightened me? Certainly the prediction by Bill Gates and his team that an epidemic like the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed 50 million people could happen again today—and that in the first 200 days it could kill 33 million people. That’s almost as many people as AIDS has killed over four decades. Even scarier was the Bank of America/Merrill Lynch assessment that the threat of a global pandemic could claim more than 300 million lives and cost the global economy as much as US$3.5 trillion.There are many things to be concerned about in this world, justifiably. Terrorism, global warming, the undermining of democracy by dark forces. (The Patriots winning yet another Super Bowl) I know that we are, or certainly should be, concerned about the potential carnage that might be wrought by some lunatic (you know the one) doing something in a fit of pique over an insulting tweet, and sending considerable supplies of glowing ordnance rocketing about the planet. Millions would perish. Landscapes would be rendered uninhabitable for decades, if not centuries, if not forever. A worldwide engagement in such insanity would slaughter hundreds of millions. We have experienced large-scale human die-offs before, in wars, of course, but there are other sorts of global catastrophes (defined as events that could wipe out 10% of humanity) that could kill even more.

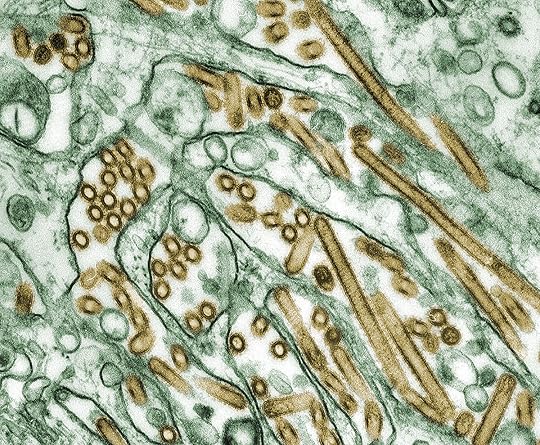

The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 may have killed as much as 5% of the world population. Some outbreaks since then infected over a third of the world’s population (e.g., pandemic influenza), whereas others killed over half of people infected (e.g., Ebola or SARS). If a disease were to emerge that was as transmissible as the flu and as lethal as Ebola, the results could be catastrophic. Fortunately, this rarely transpires, but it is possible that it could, for example with the H5N1 influenza virus. - from the Global Catastrophic Risks reportThere may not be a lot we can do about deranged leaders, other than vote them out of office, where untampered voting is an option. But there is a lot we can do to take on the growing challenges of potential epidemics and pandemics. Preventing the emergence of a global deadly pandemic afflicting vast swaths of the world’s people can save as many lives, and maybe even more lives, than averting a nuclear war. This is the point of The End of Epidemics.

Once the world woke up to the crisis, there was a generous outpouring of assistance. As the response peaked, I was consumed by nagging questions: Where will we be four or five years from now? Will the world have gone back to sleep? What’s needed to protect the world from future outbreaks? To find the answers, I explored the lessons from epidemics over the last century – smallpox, AIDS, SARS, avian flu, swine flu, Ebola, Zika – and I drew on some of the best minds, experienced professionals and committed citizen activists in global health, infectious disease, and pandemic preparedness. - from the MSH site

As with war, where common illness can take more lives than war injuries, epidemics sometimes take more lives from disruption of primary healthcare than from the epidemic itself. Because health workers are diverted to emergency response centers and health facilities are sometimes closed, epidemics can also disrupt routine public health care needs such as immunization, treatment of acute illness, and facility-based births.He looks not only at how we manage to put our hands over our ears and rattle out sound-blocking la-la-la-la-la-la noises, but takes it a step further to try to understand why we do that. He also reports on some remarkable success stories, including, over a long-term, the West coming to grips with the HIV crisis to the point where, while still a major life-threatening disease, it is now a manageable long-term condition and not an instant death-sentence. With concentrated and persistent effort progress can be made. Quick cites some other remarkable success stories in Africa that have received scant coverage in Western media. He gets specific on how much money would be needed to undertake the program he proposes, (chicken feed) and compares that with the cost of failing to do so.

in some places — including Southern California, Pennsylvania and central Texas — some hospitals have seen so many flu patients that they had to set up triage tents or turn other patients away. Local shortages of antiviral medications and flu vaccines have been reported, and the C.D.C. said patients may have to call several pharmacies to find shots or to fulfill prescriptions.