Stephen had often heard Jack say, when life at sea grew more trying than the human frame could bear, ‘that it was no use whining’

and again,

‘ Have I been plying the ocean with a parcel of Stoics all this time?’ he wondered. ‘Or in my ignorance am I myself somewhat over-timid?’

Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin continue on their circumnavigation of the globe, cca. 1812, facing inclement weather, natural disasters, pirates, political betrayals and more aboard the frigate ‘Surprise’.

Jack is the captain and Stephen the medical officer/resident spy aboard this privateer ship with a volunteer crew sent on a mission to South America to foment rebellion against Spain.

As the sixteenth book in the series and the fourth episode of this singular voyage around the world, I would not recommend it to new readers, but for old hands like me, it is one of the best instalments so far from Patrick O’Brian.

>>><<<>>><<<

We start the crossing of the Pacific right after the events of Clarissa Oakes, with the chasing of the ‘Franklin’, an American privateer ship commissioned by French agent Dutourd to colonise the Moahu islands.

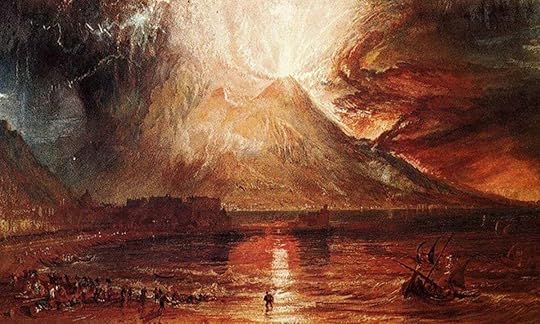

After sailing through unusually dark red seas, both ships are wrecked by firebombs in the night, with many casualties and loss of canvas and masts:

They were some distance from one another, both apparently wrecks, floating but out of control: beyond them, to windward, a newly-arisen island of black rock and cinders. It no longer shot out fire, but every now and then, with an enormous shriek, a vast jet of steam leapt from the crater, mingled with ash and volcanic gases.

An underwater volcanic explosion is just an appetizer on the menu of dangers prepared by the author for the crew of the ‘Surprise’, as they head for the coast of Peru: well armed pirates to be fought, tropical diseases, religious tensions aboard the mixed crew [‘It is remarkable,’ observed Stephen after a pause, ‘that the Surprise, with her many sects, should be such a peaceful ship.’], contrary winds fought in an open boat without water or food, icebergs to the south of Tierra del Fuego, being chased in turn by a better armed American frigate, being struck by lightning and later being stranded without a rudder in the middle of the ocean.

‘ Ah, Doctor, things is very bad,’ said Joe Plaice. ‘ I have never heard anything so dreadful as the loss of a rudder five thousand miles from land.’

As my opening quotes already pointed out, only a Stoic should set out at sea in a vessel that relies only on wind and human skill to reach destination. Captain Jack Aubrey and his loyal crew are both stoics and resourceful, while Stephen Maturin is not a shabby fighter himself, especially on land where his secret identity as a British agent often lands him in deadly perils.

‘A wind-gall to windward means rain, as you know very well,’ said Jack. ‘But a wind-gall to leeward means very dirty weather indeed. So Joe, you had better make another cast: let us eat while we can.’

>>><<<>>><<<

The main ingredients that have made me an avid follower of the ‘Surprise’ around the globe are presented in this episode with the usual panache and subtle humour of the author, still making fun of Stephen’s unfamiliarity with the jargon and of his clumsiness among ropes and wooden traps after so many years aboard ship:

Presently you will see that twin jury mainmast of hers replaced by something less horrible made up from everything you can imagine by Mr. Bentley and that valuable carpenter we rescued: upper tree, side-trees, heel-pieces, side-fishes, cheeks, front-fish and cant-pieces, all scarfed, coaked, bolted, hooped and woolded together; it will be a wonderful sight when it is finished, as solid as the Ark of the Covenant.

This nautical babble is balanced by the still fresh enthusiasm for the natural world and for the many incredible sights, plants and animals encountered, studied and preserved in the trunks of the good doctor.

‘I long to see the high Andes – tread the virgin snow, and view the condor on her nest, the puma in his lair. I do not mention the higher saxifrages.’

[He doesn’t mention it probably because this a reference to Dr. Maturin’s habit of chewing coca leaves, one more reason for him to look forward to his visit to the high Andes]

Stephen gets his wish after the ‘Surprise’ finally reaches Callao, when he is forced to flee through the high mountain passes after his plot to start a revolution in Peru is betrayed by Dutourd. The journey across the Andes is just as fascinating for me as the chapters at sea, and sometimes even more dangerous.

He ran unsteadily to the nearest. The leaves were like those of an agave, fierce-pointed and with hooked thorns all along their sides: the great spike was an ordered mass of close-packed flowers, pale yellow, thousands and thousands of them. ‘Mother of God,’ he said. After a while, ‘ It is a bromeliad.’

‘Yes, sir, said Eduardo, delighted, proprietorial. ‘We call it a puya.’

>>><<<>>><<<

Long days of crossing the ocean are also an occasion for the two friends to engage in their favourite pastime of playing classical music on cello and violin and to dabble in more philosophical discussions.

One of the subjects is slavery, something the British empire was still promoting in 1812. Patrick O’Brian, through the voice of Stephen Maturin, is not shy about his condemnation of this abominable practice, recounting a past incident in the Caribbean:

‘Why, Stephen, you are in quite a passion.’

‘So I am. It is a retrospective passion, sure, but I feel it still. Thinking of that ill-looking, flabby ornamented conceited self-complacent ignorant shallow mean-spirited cowardly young shite with absolute power over fifteen hundred blacks makes me fairly tremble even now – it moves me to grossness. I should have kicked him if ladies had not been present.’

Even more welcome for me is finally a discussion of something that has bothered me right from the first volume of the series: the fact that Jack Aubrey has no scruples about attacking civilian ships, under the most shallow excuses that they are from nations his country is at war with. I have always considered this practice no better than government sponsored piracy [indeed, I feel the same way today about the seizures of private Russian property], and I finally heard somebody say it aboard the ‘Surprise’:

‘There is something profoundly discreditable about this delight in taking other men’s property away from them by force,’ observed Stephen, tuning his long neglected ‘cello, ‘taking it away openly, legally, and being praised, caressed and even decorated for doing so. I quell, or attempt to quell, the feeling every time it raises in my bosom: which it does quite often.’

On a lighter note, the author’s delight in language has been such a trademark of the series that I am now taking it for granted, but I still chuckle when I am forced to dive for a dictionary to look up atrabilious or when I pick up the highlight tool to mark a rare moment of levity:

‘The Doctor has been choked off for being a satyr,’ said Killick to Grimble.

‘What’s a satyr?’

‘What an ignorant cove you are to be sure, Art Grimble: just ignorant, is all. A satyr is a party that talks sarcastic. Choked off something cruel, he was, and his duff taken away and eaten before his eyes.’

The ‘Surprise’ and its crew have been put through the wringer by weather and by adversaries at sea, and it has been long years since they have seen the homeland. I can sympathize with the exclamation of captain Jack Aubrey that closes this volume, even as I know there are thousands of miles still to sail before his wish would be granted:

‘Harking back to this voyage, I think it was a failure upon the whole, and a costly failure; but,’ he said laughing with joy at the thought, ‘I am so happy to be homeward-bound and I am so happy, so very happy, to be alive.’