“On a warm summer night in 1947, the largest empire the world has ever seen did something no empire had done before. It gave up. The British Empire did not decline, it simply fell; and it fell proudly and majestically on its own sword. It was not forced out by revolution, nor defeated by a greater rival in battle. Its leaders did not tire or weaken. Its culture was strong and vibrant. Recently it had been victorious in the century’s definitive war. When midnight struck in Delhi on the night of 14 August 1947, a new, free Indian nation was born. In London, the time was 8:30 p.m. The world’s capital could enjoy another hour or two of a warm summer evening before the sun literally and finally set on the British Empire…”

- Alex von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire

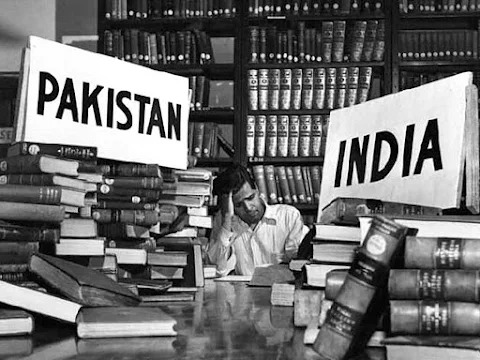

At the midnight hour of August 15, 1947, two new nations were born, and 400 million people – former subjects of the British Empire – gained their independence. It was a remarkable moment in world history, and the highpoint of a remarkable anticolonial movement that used relentless moral pressure to attain its ends.

The achievement, however, was marred by explosive acts of violence both before and after the so-called “partition” that created Pakistan and India. Millions of Muslims left India, while millions of Hindus and Sikhs left Pakistan (which was divided into two halves, its eastern portion later becoming Bangladesh). During these massive population exchanges, there were riots, thefts, beatings, sexual assaults, and countless deaths, with the final tally of fatalities typically set at a million.

This is a hugely complex tale of tragedy in the midst of triumph, one that would take several volumes to properly address. In Indian Summer, Alex von Tunzelmann manages to distill it to 318 sharply-written pages of text. To do this, she takes a top-down approach, and runs the narrative through a small handful of marvelously-sketched characters, focusing on intimate moments rather than the grand sweep of events.

***

Three people in particular form the core of Indian Summer. The first is Louis “Dickie” Mountbatten, a pomp-loving British naval officer of limited ability, who nevertheless parlayed his closeness with the Royal family into prominent postings, including the last Viceroy and first Governor-General of India.

The second is his wife, Edwina, a fantastically wealthy woman who – until setting off to India with her husband – was known mostly for her extramarital affairs, which Dickie condoned in a very English way. Later, she rose to the occasion and did her best to help partition’s victims.

The third is Jawaharlal Nehru, a leader in the Indian nationalist movement, and India’s first prime minister following independence. A fascinating figure, a proponent of secularism and democracy, it is his relationship with Edwina Mountbatten that provides the book its beating heart. Though von Tunzelmann does not venture whether their relationship was platonic or sexual, it was undoubtedly intense, their surviving letters speaking to a vivid connection.

Beyond this trifecta, von Tunzelmann also pays close attention to Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the father of Pakistan; Mohandas Gandhi, the leader of a massive nonviolent resistance to British rule; Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Jawaharlal (and no relation to the Mahatma), who later took her own turn as a controversial prime minister, after which she was assassinated by her own bodyguards; and Winston Churchill, portrayed as a bitter relic of imperialism.

Von Tunzelmann is generous and empathetic in her portrayals, and perceptive in her conclusions. Gandhi, for instance, has transcended his humanity, and become more a symbol than a man, his very name synonymous with peace and goodness. Despite working within a confined page count, though, von Tunzelmann does an excellent job placing him back into his historical context, discussing not just his righteousness – especially his last fasts – but his occasional tactical mistakes, including quarrels with Nehru that had considerable consequences.

***

Indian Summer is a popular history, not an academic work. It strives for accessibility. Even if you have read nothing of India’s expansive history before, von Tunzelmann has you covered. She presents a brisk outline of British rule; introduces the major players, including their backgrounds; and then follows them through the tumult, as they make their calculations, argue their points, and decide the fate of a subcontinent.

Telling a big story in a concise way requires a lot of simplification. The politics, the boundary disputes, the divisions within each division, are all mind boggling. Von Tunzelmann gives you the end-results, though she often only summarizes the pathways leading there. Mostly, she is interested in the people, especially Jawaharlal, Edwina, and Dickie.

***

Before picking this up, I had never heard of von Tunzelmann. If I’m honest, her name sounded made-up, and her dust-jacket bio presented no evidence that she is an expert in Indian history. Indeed, it said only that she went to college, and that this was her first book.

Having done a bit more research, it appears that von Tunzelmann is part of a new wave of youngish, “cool” British historians, such as Dan Jones and James Holland. Often blue-haired in pictures, she has since written a couple other books, and a screenplay to boot.

Von Tunzelmann’s prose style is exceptionally readable, filled with vivid passages, finely-set scenes, and an occasional dash of mordant wit. Not being an expert in this area, I can’t speak to her use of sources, other than to note that she relies heavily on personal correspondence. She writes with deep feeling, which allows her to land some emotional blows. But there is also a strange reticence, times when it feels like von Tunzelmann is holding back. She does not make any attempt to explore the burning did-they-or-didn’t-they question of Edwina and Jawaharlal. Similarly, von Tunzelmann does not address the child abuse allegations against Dickie that have arisen in recent years (allegations that have dogged other British officers, and which have their genesis in a tabloid).

It occasionally seems that after devoting herself to these people, von Tunzelmann is trying to protect them. It is also possible that she has elevated the importance of certain of these figures beyond what they deserve. Edwina, for example, is given a starring role in events, whereas in Ramachandra Guha’s 900-page volume on Gandhi, Edwina appears only once by name.

***

When writing about history, there is always a tension between particular acts and impersonal forces. Generally, more “serious” or academic-minded historians prefer to study the larger factors, those beyond the control of any one person. Popular historians, meanwhile, like to identify those moments when everything seems to hinge on a single decision or a single action undertaken by a fallible man or woman.

Von Tunzelmann clearly falls into the latter category. As history, Indian Summer is streamlined, deeper than a mere recapitulation, but still only scratching the surface. As drama, though, this is exceptional, featuring flawed but mostly-well-meaning individuals trying to navigate a transition of power, the likes of which had never occurred before. More than that, in Jawaharlal Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten, von Tunzelmann has created a beautiful portrait of an unusual, lasting, and passionate friendship.