“She seemed to hang suspended in a void; she had lost one personality without regaining another.”

Cornell Woolrich originally tried to emulate F. Scott Fitzgerald, but failing to hit it off in that line, he soon turned to detective fiction and pulp novels, which was a lucky thing in two ways because one F. Scott Fitzgerald is more than enough by half, and secondly, Woolrich’s pulp and detective stories are often top-notch. Among these, The Bride Wore Black is probably one of the best-known, not least so because François Truffaut made it into a film in 1968.

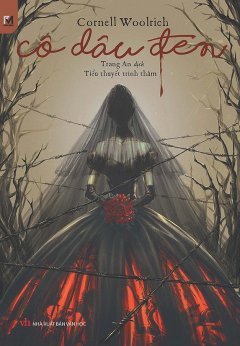

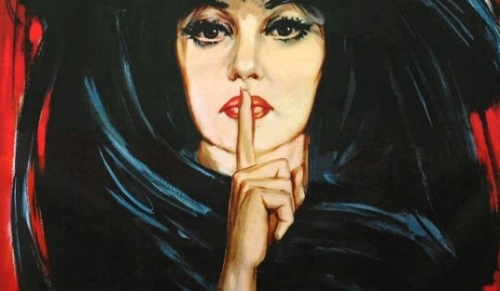

The story is relatively simple, centring on Julie Killeen, the mysterious femme fatale who sets out to kill a group of men she holds responsible for the murder of her husband on the day of their wedding, and on detective Wanger, who desperately tries to make head or tail of a series of seemingly unconnected murders and to get a few steps ahead of his quarry in order to catch her while she is trying to strike again. Julie is a remarkable woman, as protean as Alec Guinness or Lon Chaney, but better-looking, and she has a knack for anticipating in what guise she will make the most intense impression of her prospective victim. When trying to ensnare the painter Ferguson, for instance, she studies his paintings beforehand in order to know what kind of woman is most prominent in his paintings; when lulling the dreamer Mitchell, she comes as a mysteriously exotic woman, and when worming herself into the confidence of the rather respectable and unimaginative family father Moran, she slips into the role of an efficient, yet attractive young nursery school teacher. In the course of her metamorphoses, she gradually seems to lose herself, though, which might be read as a hint that her desire for revenge is eating her slowly away, a very clever turn Woolrich gives his fascinating tale of revenge, apart from the really sobering twist at the end of the tale.

Truffaut, by the way, seems to have had a good hand at making a fine kettle of fish of the novels he turned into films, which can best be seen in his adaptation of Bradbury’s dystopia Fahrenheit 451. His movie version of The Bride Wore Black paints all the male characters in the worst light possible, e.g. by making a shallow philanderer of Bliss or by turning Moran into a moron that does not shirk from making a pass at the young schoolteacher while his wife is on her visit to her supposedly dying mother, and so you do not really feel too sorry for the men his Bride kills off. This decision might be in tune with contemporary tastes and mores in that it facilitates a feminist reading of the topic, but it also takes the edge off the entire story. In the novel itself, it turns out that Julie’s victims were actually innocent, which makes the whole affair even nastier (and probably more congenial to Woolrich himself, who was a man highly dissatisfied with life and whose health and alcohol problems might have contributed considerably to strengthening a streak of bitterness in him). At the same time, even though Woolrich does not paint Julie’s victims in colours as disagreeable as Truffaut does, his novel can still be read in a feminist way in that all these men see in Julie only what they want to see in a woman, gazing at her and reading her in the light of their own desires and longings.

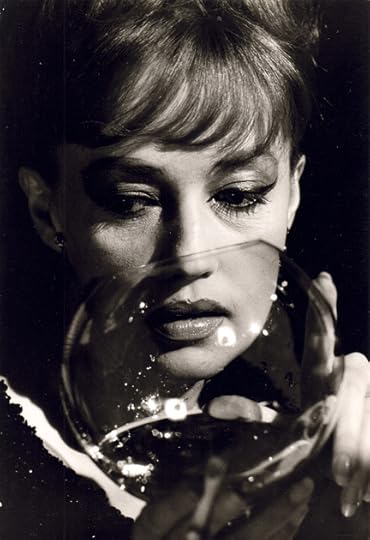

The only real advantage the movie has over the novel is the fact that the inimitable Jeanne Moreau plays the eponymous Bride. I do wonder what Woolrich would have said about this film, but when it was showing, Woolrich was already so much of a recluse due to bad health – one of his legs had had to be amputated – that he did not go to its American release.