‘A Vivid Waiting’

Is the phrase Ezra Pound employed to describe a story from James Joyce’s ‘Dubliners’ (1914) which he thought ‘something better than a story’ (Berryman, J. 1949) and an apt way to describe the experience of reading Pound’s ‘Cathay’ (1915). Something better than a translation, ‘Cathay’ gives us pause to reflect on what constitutes poetry’s general appeal. How is it that Pound, universally recognised as a great poet, often proves so difficult to read? Even in ‘Cathay’, where brevity and crisp imagist logic means that a reader can grasp the whole with barely a glance at the endnotes, there’s a certain stark dullness to what’s spelled out. The battles and the carousing are in the past, the danger and the loss is in the future, and the reader is left weirdly bell-jarred inside an air-tight present without any obvious sources of momentum.

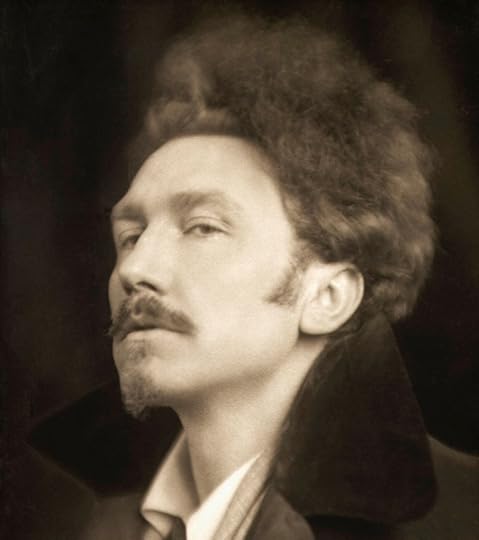

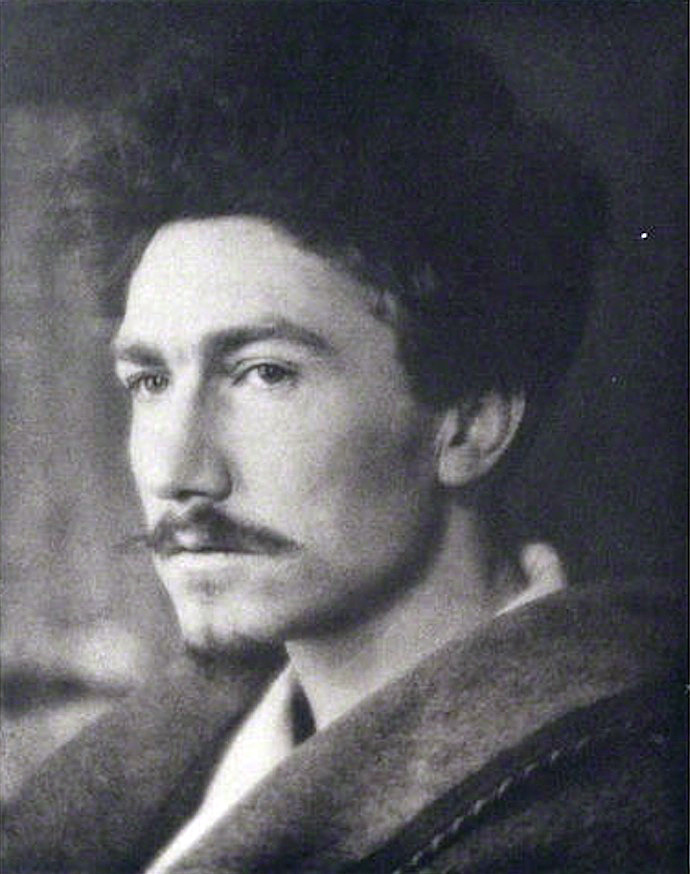

Encountering Pound for the first time as a teenager, I struggled to suspend my disbelief. Is Pound’s universal recognition a strange case of the emperor’s new words? Was Pound’s immense prestige only a result of a critical cabal bent on justifying their own expertise, when actually it’s just a matter of preferring one set of subjective word-choices over another? The suspicion that poetry was a racket spontaneously evolving from the shared likes and dislikes of a small academic elite didn’t make me feel cheated so much as disappointed: that great poems might not magically catapult you into the ecstasies of the imagination a sour lesson to learn. Nevertheless, I resolved to study the mechanism of leverage: I could be wrong.

‘Cathay’ is the medieval name for what we now know as northern China, and the title immediately signals Pound’s understanding of translation as something thoroughly dependent upon a translator’s worldview. This dependence is particularly acute here given that Pound knew very little Chinese and 'Cathay’ could better be described as a collaboration between Ernest Fenollosa’s basic word-for-character ‘crib’ and Pound’s subsequent re-envisaging of the Chinese classical sources. According to Kazuhito Hayashi, Pound’s distinctive style can be observed in his use of syntactical links and conjunctions which generate metaphysical depths not present in the originals. In ‘Poem by the Bridge of Ten-Shin’ the standard translation would have the seventh and eighth lines read:

‘Today’s men are not those of yesterday

Year after year they hang around on the bridge’ (cited in Hayashi, K, 1972)

Pound’s translation sharpens this image through adding conjunctions into a kind of spectral haunting:

‘But today’s men are not the men of the old days

Though they hang in the same way over the bridgerail’

In Pound's rendering, not only do we get an ominous image in the ambiguity of today’s men hanging ‘over’ the metallic ‘bridgerail’, but there’s also a sense that the shades of dead men are dissatisfied with those of the living. Allegedly, traditional Chinese poetry is often hard for western readers to appreciate because it is largely organised through subject matter and motifs rather than the supposedly heroic narrative arcs of western film and drama; however, with a little sketching in of the viewpoint, its implied emotional content can be brought forward. Pound claims that with ‘careful examination, [in a classical Chinese poem] we find that that everything is there, not merely by "suggestion", but by a sort of mathematical process of reduction. [Simply] consider what circumstances would be needed to produce just the words of the poem. You can play Conan Doyle if you like.' [1919]

Pound’s detective work in ‘Cathay’ results in a kind of gleaming eye-witness testimony without the melodrama or chinoiserie. Pound, the great American poet-scholar living in self-imposed exile in old Europe is also suitably placed to convey how great distances make human relationships more fraught, as described in the original poems, where a trip to a far-away market might mean one never returned. Much of ‘Cathay’ derives from the single author, Li Po, who was an itinerant court poet, whose life, if not his poetry, failed to live up to its promise of worldly success. One of the most charming elements of his poetry is his ability to marvel at wealth and opulence from a distance regardless, or perhaps because of, his own impoverishment. It is this lack of envy or reproach for his present circumstances which is arguably a key source of dignity in both Li Po and Pound’s poetry. It is as if they can enjoy the fine artifacts of civilization, whether these be ‘red jade cups’ or ‘food well set on a blue jeweled table’, through their lucid reconstruction in poetry: imagine yourself a beggar and be prepared to see a beautiful young noble woman emerge in green and purple silks, or consider those Chinese soldiers there, who wallow gracefully in their doomed fates without false notes of bravery. As soldiers the world over understand, ��Loyalty is hard to explain.’ Li Po, who struggled for patronage and covered great stretches of China on foot is a great cipher for Pound himself. All Pound need do is sample the right lines and add his lyrical inflections and he has an original timeless poem of his own. 'Cathay' will also come to serve as a model for the brilliant free-translations of Jack Spicer’s ‘Lorca’ and Stephen Rodefer’s work with ‘Villon’, where they adopt the guise of these poets as dramatic personae.

Consequently, as an expression of Pound’s world, ‘Cathay’ is not isolated from his dangerous political views. There’s a feudal governance at work in the background logic of these poems which espouses rank and wise judgement and implies all is well so long as wicked individuals don’t grow corrupt. Basically, it's a mix of Confucianism with a hint of Catholic damnation misapplied. Traditionally, defending Pound’s value as a poet has meant either a) bracketing out the politics as much as possible as an unfortunate and unnecessary addenda to otherwise technically brilliant and thoughtful poetry, or b) downplaying their virulence to a few explicit statements in the Cantos and trusting that they are caused by attributing economic unfairness to the malicious workings of an over-racialised elite. Besides, hadn’t Pound made a deathbed retraction of his fulminations against the Jewish coded ‘ursura’ in favour of a more Christian universal ‘avarice’ as the source of all evil?

Whereas the former attempt at reconciliation fails insofar as his poetry's critical animus is a large part of its dramatic content, the latter fails through ignoring what’s extant: listening to Pound’s WWII radio broadcasts will cure anyone of the illusion that Pound’s antisemitism was temporary and incidental. Rabid antisemitism is, undeniably, fundamental for his worldview as presented in the major late works, and in this regard, they bring into peculiar relief Walter Benjamin’s remark that ‘there is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism’. Pound’s poetry is the drama of a great writer whose flashes of terrific insight and wonder, as evident in ‘Cathay’, will not prevent him from unraveling a dreadful logic whose rhetoric he helped to fashion and thereby facilitate possibly the worst expression of human barbarism to date. Coming to terms with a worldview radically different from your own, however, requires a certain dignified patience which is a hallmark of civilization. Morality, on the other hand, comes from elsewhere.