What do you think?

Rate this book

189 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2006

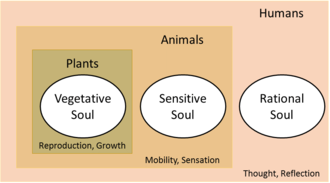

"Thought is an attribute which belongs to me: it's the only one which cannot be separated from me. I AM, I EXIST, that is for sure, however for how long? to be known, as long as the time my thought lasts"

René Descartes in: Meditationes de prima philosophia