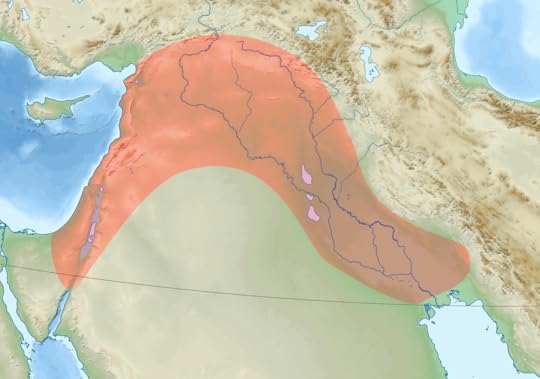

A good introduction to Mesopotamian history, but it comes with some caveats. Look for instance at this: “Into this relatively uniform, mostly undifferentiated, largely homogeneous world of subsistence farmers and peasant hamlets, the idea of civilization was born: in a single place, at a single time. From there and from then the concept spread at remarkable speed to conquer the world.”. Now look, such a text makes my hair stand on end: Kriwaczek is talking about the southern Mesopotamian city of Eridu, which he presents as the place where everything started 5,000 years ago. This is ridiculous of course. Eridu certainly was a remarkable place where the urbanist revolution and the active application of writing is very demonstrable on the basis of archaeological finds. But at the same time there were many other places in present-day southern Iraq where similar historical developments took place. And besides, all this was preceded by several millennia, in the wider area called the Fertile Crescent, where increasingly complex forms of agriculture (and irrigation), artisanal production, urbanization, and trade developed. Also, the portrayal of Eridu as the center from which the rest of the world learned about civilization is completely out of the loop, and in a way western-centrist. It is one of the great weaknesses of this book. Kriwaczek even claims that Mesopotamia is the beginning of everything, an “explosion of creativity” to which Western civilization (there’s that centrism again) has barely added anything.

And Kriwaczek engages in other exaggerations, such as his stress on the great continuity in the very long history of Mesopotamia: “Throughout all that time (…) Mesopotamia preserved a single civilization, using one unique system of writing, cuneiform, from beginning to end; and with a single, continuously evolving literary, artistic, iconographic, mathematical, scientific, and religious tradition.” Now, there certainly is a remarkable continuity, but within that long span of almost 3 millennia there also is quite a bit of evolution and diversity. I think the author here wanted to be a little too didactic. Take, for instance, his depiction of the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur (2100-2000 bce) as an outright communist regime. This not only is absurdly anachronistic, but this way he also ignores the distortion that plagues the source material of all Mesopotamian history (namely the quantitative over-representation of the extensive bureaucratic archives of palaces and temples). Just one other default: his presentation of Hebrew monotheism as a logical continuation of a trend that already started on the Assyrian-Babylonian side is controversial to say the least (based on a single hypothetical study).

And yet there are also curiously positive aspects to Kriwaczek's coarse brush. Repeatedly, his bold statements can be called enticing. His view of the development of culture and civilization as an eternal, dynamic struggle between conservatives and progressives, for example, is quite inspiring: “The actual story would have to allow for the everlasting conflict between progressives and conservatives, between the forward and backward looking, between those who propose 'let's do something new' and those who think 'the old ways are best', those who say 'let's improve this' and those who think 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it'. No great shift in culture ever took place without such a contest.”

In the same vein, I also appreciated the insight of the drastic step that was the development of a real empire: “Now you are no longer leader merely of your own people but of a mixed multitude. To take that step demands a new way of seeing yourself, one that underplays your particular origin and your service to your particular god, and that makes much more of your individual and personal qualities, irrespective of your original language or culture. To be an emperor, in other words, is to be out on your own, no longer among your own kind. That demands a certain kind of heroic self-sufficiency.”

And Kriwaczek also made it clear to me how the production of bronze weaponry started not only a military, but also a social and cultural revolution, namely through the emergence of heroic heroism: “Armed with swords, warriors no longer form an indistinguishable mass, but each stands out as an individual fighter, placing himself a pace or so from his opponent and, rather than grappling hand to hand, or laying about him like a wild beast with club or axe, he skillfully trades precisely aimed and calculated thrusts, parries, lunges and ripostes. Fighting like this can be, and long has been, treated as an art with its own aesthetic.”

As such, for the first time, the individual came to the fore as a decisive element in the ins and outs of human life: “The age of Sargon and Naram-Sin switched the focus to the human world, and introduced a new conception of the meaning of the universe: one that made people rather than gods the principal subjects of the Mesopotamian story. Humanity was now in control. Men – and women – became rulers of their own destiny. To be sure, people were still pious, still presented sacrifices to the temples, offered the libations, performed the rites, invoked the gods' names at every opportunity. But the piety of the age now had a quite different flavor.”

Finally, there is Kriwaczek's fundamental consideration of the phenomenon of human civilization. He rightly states that it was based on a form of hubris from the start: “This was a revolutionary moment in human history. The incomers were consciously aiming at nothing less than changing the world. They were the very first to adopt the principle that has driven progress and advancement throughout history, and still motivates most of us in modern times: the conviction that it is humanity's right, its mission and its destiny to transform and improve on nature and become her master.” As Kriwaczek rightly writes, this form of hubris now threatens humanity itself.

All in all, therefore, this is a thoroughly grounded book, but one with both enticing and undue views.