What do you think?

Rate this book

ebook

First published January 1, 2012

"Whoso findeth," his friend congratulated him at his wedding fifty-two years before, and this finding continues today—find: the wisdom in the Torah, a good wife, a peaceful life, down to the last shovelful of earth on the coffin; find: a death easy as a kiss, "like the kiss with which the Lord awoke Adam to life," he blew breath into his nose, and one day, if you're lucky, he'll gently, lightly kiss it away again.Sure, she could have said this more simply, but the intricacy of its fragmentation and repetitions are the essence of what might be called Erpenbeck's high style. It is even more resonant in the German;* the main reason why I abandoned my first reading is that I was aware of so many other layers of reference beneath the surface that I feared I was missing. So kudos to translator Susan Bernofsky for retaining so much of the poetry, and not trying to turn everything into prose. Not that Erpenbeck's "prose" level is to be sneezed at either. She has a way of writing with devastating simplicity, as in the following, a complete chapter, set as a kind of epilogue to Book II:

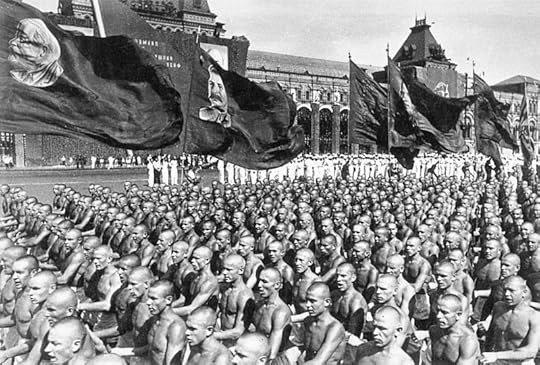

In 1944 in a small forest of birch trees, a notebook filled with handwritten diary entries will fall to the ground when a sentry uses his rifle butt to push a young woman to the ground, and she tries to protect herself with arms she had previously been using to clutch the notebook to her chest. The book will fall in the mud, and the woman will not be able to return to pick it up again. For a while the book will remain lying there, wind and rain will turn its pages, footsteps will pass over it, until all the secrets written there are the same color as the mud.Much of the success of Erpenbeck's breakout novel Visitation came from the balance of these two styles: the poetic invocation of a Brandenburg lake over decades, centuries, and aeons, and the simple account of the brief lives led in a house on its shores. The End of Days attempts much the same thing; it is also an account of an entire century of German history, told through sharply characterized vignettes. So is this latest novel as good as its predecessor? I would have to say not quite. While it mesmerized me with its poetic vision and infolded layers of narrative, I missed the balance of the earlier book; I was intrigued, but seldom devastated. In particular, the lethal absurdity of Soviet bureaucracy which constitutes the whole of Book III first confused and then annoyed me, as communist dialectic tends to do. I was glad to return to a saner world in Book IV.

Finden und finden," hat ihm sein Freund bei der Hochzeit gewünscht, zweiundsiebzig Jahre zuvor, und so dauert das Finden bis heute an, finden, die Weisheit in der Tora, finden, eine gute Frau, finden, ein friedliches Leben bis zur letzten Schaufel Erde, die auf den Leichnam geworfen wird, finden, einen Tod, der leicht ist wie ein Kuss, "wie der Kuss, mit den der Herr Adam zum Leben erweckt hat," Atem hat er ihm durch die Nase geblasen, und küsst den Atem, wenn man Glück hat, eines Tages sanft und leicht wieder fort.The repetitions of the words finden, Kuss, and Atem show Erpenbeck's poetic bent better than anything else. Also the easy flowing of one idea into another, almost regardless of syntax, with nothing stronger than a comma. Looking at this again, I can't help feeling that Susan Bernofsky may have overpunctuated her translation, trying to give logical structure to something that is merely intended as a free sequence of thoughts. Perhaps something like the following?

Find and find, his friend wished him at his wedding, seventy-two years earlier, and the finding continues to this day, find, wisdom in the Torah, find, a good wife, find, a peaceful life until the last shovelful of earth is tossed on the corpse, find, a death as easy as a kiss, the breath with which the Lord waked Adam to life, the breath that he blew into his nostrils, and the breath that, if one is lucky, he will one day kiss softly and gently away. [translation mine]