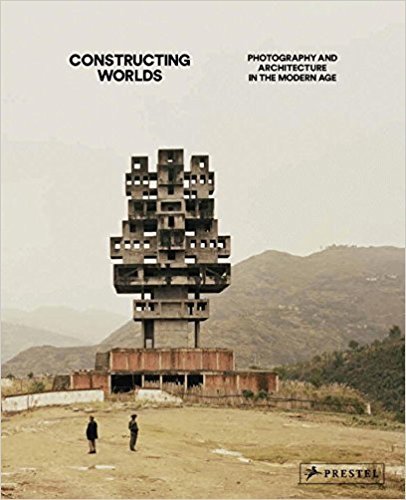

4.5 Stars!

This book shows the huge importance that photography has had and continues to have on architecture, the long running alliance between them has played a significant role in benefiting both art forms and allowing them to enjoy a wider audience.

In terms of quality and variety we are very much spoiled for choice. From many schools and many eras we get a satisfying range of photography and architecture. Berenice Abbott’s “Night View” of New York from 1932 could have been taken last night and reduces the neon lights to a landscape of smouldering coals. Her “City Arabesque” from 1938 destroys our idea of scale making you believe that you could lift up the buildings and move them around as you please. In another image, we find the tenants’ washing hanging in the air like the forlorn sails of an abandoned pirate ship.

The bland, sterility of Julius Shulman’s shots of post-war American houses, that he did for aspirational lifestyle magazines, has a chilling quality that you would normally associate more with a sci-fi dystopia. Then there are Lucien Herve’s crisp, sharp images of Le Corbusier’s work, the High Court of Justice in Chandigarh from 1955, which give the building an appearance somewhere between a giant’s workshop and a derelict warehouse.

Ed Ruscha’s aerial shots of LA parking lots which are so bewildering that they could easily be segments from an open cast mine. Then we have Bernd and Hilla Becher’s stark, brutalist monolithic water towers, which almost look primed for take-off. Many of Stephen Shore’s sun soaked shots of cities in the US, resemble scenes from some forgotten 70s/80s daytime soap opera.

Thomas Struth’s streetscapes, possess an eerie stillness, his shot of Buskoe Dong in Pyongyang from 2007 is a ghastly concrete nightmare, which takes the idea of brutalism to a terrifying extreme and really feeds into the idea of the Hermit Kingdom as one great prison. Simon Norfolk’s incriminating depiction of Afghan ruins, exposes the true cost of criminal capitalism. The honeyed light only briefly detracts from the extent of the devastation, at the hands of various murderous Russian, American and British regimes have inflicted stretching back centuries.

Guy Tillim’s crumbling apartment buildings, in Beira in Mozambique (2007) present quite an extraordinary juxtaposition against the tropical background, which looks eager to reclaim its land and Nadav Kander’s images of China’s accelerated progress, speak like smeared, moody landscapes tinged with loss and regret.

As this book so beautifully demonstrates the marriage between architecture and photography is not only a vital one, but an incredibly inventive and fruitful one which benefits all concerned. This is an absolute treat of a collection and I would recommend to anyone with the slightest interest in architecture or photography.