What do you think?

Rate this book

70 pages, Paperback

First published January 14, 1889

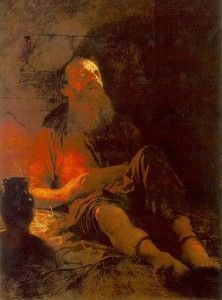

It was decided that the lawyer must undergo his imprisonment under the strictest observation, in a garden-wing of the banker's house. It was agreed that during the period he would be deprived of the right to cross the threshold, to see living people, to hear human voices, and to receive letters and newspapers. He was permitted to have a musical instrument, to read books, to write letters, to drink wine and smoke tobacco. By the agreement he could communicate, but only in silence, with the outside world through a little window specially constructed for this purpose. Everything necessary, books, music, wine, he could receive in any quantity by sending a note through the window.The plot is straightforward, but the ideas and prose elevate it to something that is well worth reading and pondering. It's a different, thoughtful kind of tale with one major twist to it that I didn't see coming. And I don't think the final resolution - for either the banker or the lawyer - is as straightforward as it may seem at first glance. George Saunders, author of Lincoln in the Bardo, says it succinctly here, in an interview where he talks about why he loves Chekhov's stories:

That’s one of my favorite things about Chekhov: his ability to embody what I call “on the other hand” thinking. He'll put something out with a great deal of certainty and beauty and passion, absolutely convincing you—and then he goes, “On the other hand,” and completely undermines it. At the end of this story you ask, “Chekhov, is happiness a blessing or a curse?” And he’s like, “Yeah, exactly.”Yeah, exactly.

There had been many clever men there, and there had been interesting conversations.