What do you think?

Rate this book

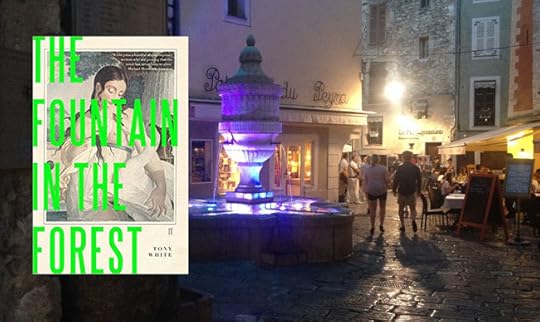

Paperback

First published January 2, 2018

The Fountain in the Forest and the two novels that follow are mapped against a specific period in UK history: a brief interregnum of ninety days (or nine revolutionary weeks, according to Sylvain Maréchal’s decimal calendar) from the end of the UK Miners’ Strike on 3 March 1985 to the Battle of the Beanfield on 1 June. Each chapter is mapped against one day in 1985, converted into the French Revolutionary Calendar, but as well as being shot through with the daily symbols from the Revolutionary Calendar, The Fountain in the Forest also uses a mandated vocabulary, i.e. a predetermined list of words that must be incorporated into the text – namely, all of the solutions to the Guardian Quick Crossword from each of those same days in 1985.Now I should acknowledge this is in an afterword, and sometimes with Oulipan novels (see my review of Sphinx) it can be ideal to start the book unaware of the constraint. Indeed, famously if perhaps apocryphally, some early reviews of the classic Oulipan work, Perec's La disparition failed to notice that it was written without the letter 'e', despite the clues such as the main character called Voyl (Vowl in the English translation, The Void). Here however, all of the publicity surrounding the book, such as the author's own crossword used to promote it, rather suggest one is expected to know in advance, and indeed the mandated words are highlighted in bold in the text as and when they occur.

Like any British policeman who had been brought up on the true-crime stories of the early twentieth century, Detective Sergeant Rex King recognised the jagged, hairy leaves and the sickly-looking yellowish and purple-veined five-pointed flowers immediately. It was henbane – Hyoscyamus niger – source of the deadly alkaloid scopolamine. This was the poison that, in 1910, the notorious ‘Doctor’ Hawley Harvey Crippen had used to kill Cora Turnerhenbane being ones of the answers to the Guardian Quick Crossword No. 4649, from Monday 4 March 1985, the others being, in order of their appearance in the novel's text, cabinet, Emma, least, cavil, prosaic, indispensable, Gallup, reason, Tuesday, night-watchman, Banda, icicles, vinegar, spice, Mark Twain, Iliad, my type, aspect, wallpaper, thrill, ebb-tide, tea-shop, geyser, Eric and enemy.

the story of the Republican calendar contains — in almost conceptually distilled form — the history of our own modern time schema, restoring to life the assumptions, hopes and blind spots about the human construction of value and meaning that remain with us today.The community in La Fontaine en Forêt also adopt the calendar, and in particular it's way that each day of the year reflects a particular aspect of rural life.

No one else had the almanac, but even if they had, no-one really understood the particular method Pythag used to calculate this. They just took his word for it, enjoying the seasonal tone and flavour of the plants and herbs, the agricultural tools and foodstuffs that were thus named. They enjoyed the way that these names harked back to a simpler, pre-industrial way of life, as well as the basically irreligious and non-hierarchical structure that this implied, in contrast to the regular calendar with its saints’ days and Sabbaths, high days and holidays.Each of the chapter's is named after one such day and the book then contains another piece of unrevealed mandated vocabulary, namely to include this within the chapter, but left for the reader to find. Some are used for character's names and others inserted similarly to the crossword answers; so, for example, the stream of thought containing the "platypus in a porn film” analogy also has, a few lines later, "as powerless as Popeye without his spinach", both in the Chapter Epinard / Spinach.