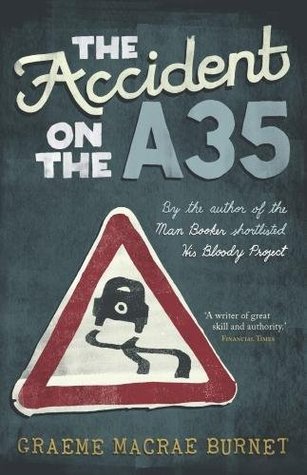

Scottish writer Graeme Macrae Burnet is my top new discovery this year, and I have now read all three of his novels, including the outstanding HIS BLOODY PROJECT, which was short-listed for the 2017 Booker Prize (and I was rooting for him to win). THE ACCIDENT ON THE A 35, like THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ADELE BUDEAU, takes place in the small French town of Saint-Louis, close to the Swiss border.

As with Adele Budeau, we learn in the Forward (and more in the Afterword) that this detective story was actually one of two outstanding manuscripts by the “acclaimed” (fictional) author, Raymond Brunet, delivered to the publisher on the day of his mother’s death. Brunet had died years earlier in a suicide, which leaves the reader wondering why these manuscripts weren’t sent until this very day. Burnet is such a tease with his crafty meta-fiction!

The lugubrious Detective Gorski is back, with an accident on his hands. The 60-ish year-old driver, Bertrand Barthelme, a successful solicitor, appears to have fallen asleep at the wheel, rolled down a slope, hit a tree, and instantly died. No mystery there, until Gorski is asked by the attractive young widow, Lucette, to look further into the accident, due to an unexplained route Bertrand took on the night in question. Gorski’s vulnerability to Lucette, like every other detail in this story, has a hand in changing the course of events. When it is apparent that a murder occurred in a neighboring town on the night of Bertrand’s death, Gorski starts making connections.

The deceased’s seventeen-year-old son, Raymond (the same name as the “author’s”), appears relieved by his father’s death. “…a certain lightness; a feeling similar to that which he experienced when the school year ended for summer, or when spring arrived and it became possible to leave the house without a winter coat.”

Raymond is a loner, but has two close friends—male and female. He’s an eccentric boy that appears to lack empathy. He prefers to read, currently preoccupied by Sartre. There does seem to be a sly NO EXIT sprinkling in the story, as this novel often explores the concept of subjectivity—looking at oneself as an object and seeing oneself as the self appears to others. “How should I react?" thinks Raymond, when told by Gorski that his father has died. “He glanced on the floor to buy time. Then he sat on the bed. That was good. That was what people did in such circumstances…” This was a boy who wasn’t guilty of a crime--except perhaps the crime of unkind thoughts.

Several of the characters periodically digress into deductive reasoning concerning present actions, and there is a consciousness—or, more accurately, self-consciousness, as they ponder the reaction of others and themselves. In this way, even small gestures or inconsequential and innocent actions take on significance. A stray look from a stranger never ceases to alarm Raymond, especially as he follows-up on an address he found in his father’s desk. This leads him to another town where he subsequently begins to act out in reckless and risky behaviors.

As the narrative moves forward, the reader witnesses a solid sense of isolation between characters, and even between characters and their immediate environment. It accentuates an existential angst that is pervasive here. Regarding Raymond’s stiff-necked father, “Even in his absence…when Raymond and his mother shared a light-hearted moment, they would restrain themselves, as if their deeds might be reported to the authorities.”

Background details of the family are revealed gradually through the tale, poignant moments and random encounters that tunnel its way toward the visceral denouement. Ongoing marital problems between Gorski and his wife, as well as unanswered questions regarding his own childhood, add a layer of motif in the vessels of the main story. The plot is lightly told while the psychological tension ratchets up.

As the reader is led back and forth through the past and present, the narrative gains ground and stimulates our curiosity subtly but surely. The book’s framework consists of small stones that gather bits of moss as they roll on, page after page. “Something HAD happened. And it happened without any exertion of will on his part. One thing had simply followed from another.”

Hauntingly atmospheric, mordantly witty, and brilliantly written, Burnet’s book will leave you with many questions of your own about the characters and events. Motivations are sublime and secondary characters are written just as skillfully as the primary ones, with a tinge of undertone that makes you pause, and with the force and nuance suggestive of a Dostoevsky novel. The dissection of small-town life is reminiscent of Karin Fossum's THE INDIAN BRIDE. This is one to read again and again. I can’t wait for the "other" manuscript to surface. I will be at the front of the queue.