What do you think?

Rate this book

168 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1950

JIRO

You really are pretty. But if you strip away the skin, what have you got but a skull?

BEAUTY

You're horrid. I've never thought about such a thing. (She touches her face.)

JIRO

Do you suppose that some skulls rank as beauties among their kind?

BEAUTY

I imagine so. Some must, I'm sure.

JIRO

What extraordinary confidence! But when I was kissed just now I knew that underneath your cheeks your bones were laughing.

BEAUTY

If my face laughs the bones laugh too.

JIRO

Is that what you have to say for yourself? You should say when your face laughs your bones are laughing. That's for sure. But the bones of your face laugh also when your face is crying. The bones say: "Laugh if you want. Cry if you want. Our turn will be coming soon."

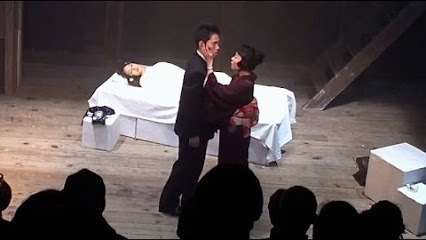

JITSUKO

I have only known Hanako since she lost her mind. That has made her supremely beautiful. The commonplace dreams she had when she was sane have now been completely purified and have become precious, strange jewels that lie beyond your comprehension.

YOSHIO

Say what you will, flesh is in those dreams.