What do you think?

Rate this book

384 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2019

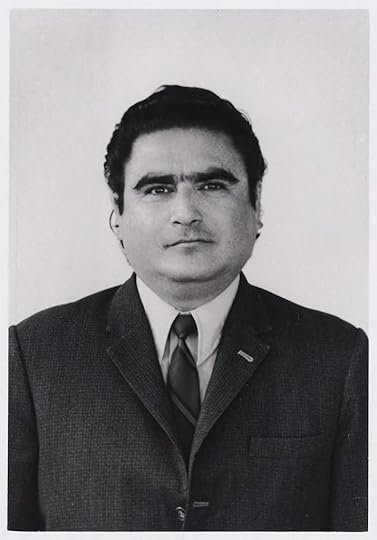

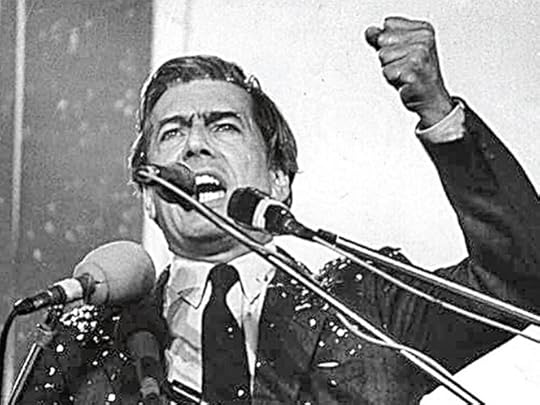

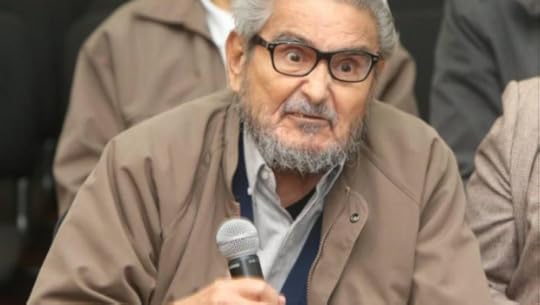

From the outside, Shining Path could appear to be an invulnerable force. A War Machine, some called it. Lurgio and his fellow fighters had no such illusions in their stone shelters. They came mostly from peasant families, a ragged band of children and teens, who had just a few rifles and not many more bullets.The book opens with a prosecutor’s visit and search of a prison cell, the occupant, nearing eighty, one Abimael Guzman, jailed for over twenty years, and destined to remain so for the rest of his dwindling days. It is a punishment deemed far too lenient by many. Guzman had led the Peruvian insurgency known as The Shining Path, (Sendero Luminoso) causing the deaths of thousands of his countrymen. All in a good cause, he still thinks. And he still dreams. But the reality is that his dream is done.

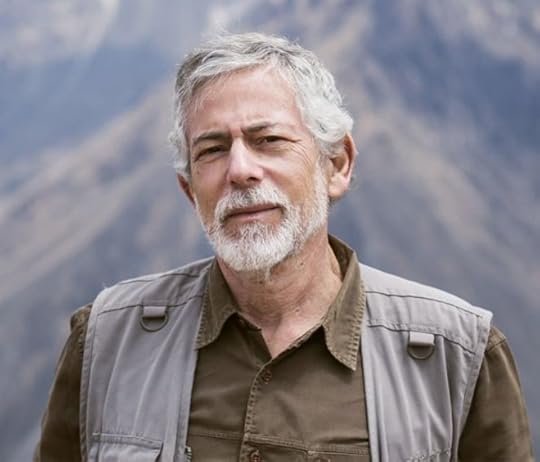

It took its name from the maxim of the founder of Peru’s first communist party, José Carlos Mariátegui: “El Marxismo-Leninismo abrirá el sendero luminoso hacia la revolución” (“Marxism-Leninism will open the shining path to revolution”) - from BritannicaOrin Starn and Miguel La Serna have written a fascinating history of the movement. In addition to timelines and major events, they take a close look at the personalities involved and offer diverse perspectives. They look at origins of the movement and motivations of the people who participated in it.

“The material can be complicated, but we tried to craft it into a story that had characters the reader might care about,” Starn said. “It was a challenge to weave this plot together. It has a Greek tragic arc. High hopes for revolution. The blood of war and then destruction and loss, with nothing achieved at all.” - from the Duke Today articleI found that the looks at Guzman and Augusta did not satisfactorily explain how such middle class people could become so godawful bloodthirsty. Augusta came from a land-holding, educated family, with no indication of fanaticism in her upbringing. Guzman had a less charmed childhood, but it does not sound horrific. He, in particular, seems to go through a metamorphosis from political leader to nutcase. I heartily recommend for your consideration the book, Tyrannical Minds, for a look at some other leaders who have seriously gone off the rails. Like most would-be despots Guzman got off on elevating his image among his followers, portraying himself as a leader on par with Mao, Lenin and Marx. He also never met a rule he was not comfortable bending or breaking to suit his own purposes. Too much praise, and too much early success clearly went to his head. But what was it in his background that made him so susceptible to the attractions of megalomania? This is a history, not a psychoanalysis, so one can be forgiven for not offering a clinical diagnosis, but it would have been quite interesting to see where he fit on the tyrannical mind scale. By the end, Guzman seemed just this side of declaring the official language of Peru to be Swedish.

Some party leaders wondered about Augusta’s death, and, if she hung herself, exactly why. Elvia Zanabria, Comrade Juana, suggested a formal investigation for the party record….Abimael refused to authorize an inquiry, which prompted the disillusioned Oscar Ramirez to question the suicide story in his own mind. Had Augusta been sick, perhaps dying from a fast-spreading cancer. Could she have been killed in some dispute over ideology and the revolution? Or because Elena and Abimael wanted out of the way to proceed with a covert love affair? It was typically self-serving, Ramirez thought, that Abimael professed his commitment to transparency and clarity, and yet rejected any party investigation into Augusta’s death. “Whenever [party norms] did not serve his personal interests, he just ignored them or pushed them aside,” Ramirez said years later.

Both Lenin and Mao displayed a considerable willingness to compromise in order to achieve revolutionary victory. Despite his diatribes against concessions and the incorrect line, the Bolshevik leader accepted the German kaiser’s help against the tsar. Mao allied with Chiang Kai-chek’s Nationalists to fight the Japanese before seizing China for himself by driving them to Taiwan…By contrast, the senderistas maintained their absolute contempt for elections and any negotiations with the government. They never developed a strategy for dealing with disaffected villagers besides trying to bludgeon them into submission. That brutality was self-defeating,,,