What do you think?

Rate this book

526 pages, Kindle Edition

First published November 11, 2015

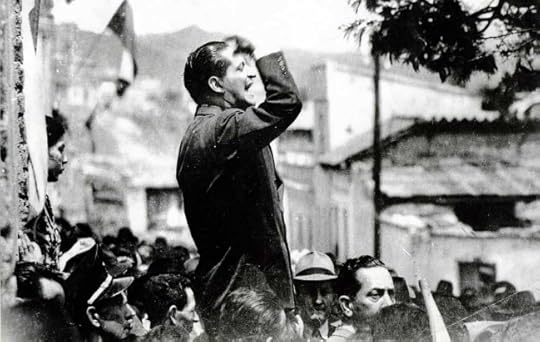

He waited for the last group of uniformed schoolchildren to leave before going up to the second floor, where a glass case protected the suit Gaitán was wearing on the day of his assassination, and then he began to shatter the thick glass with a knuckle-duster. He managed to put his hand on the shoulder of the midnight-blue jacket, but he didn’t have time for anything else: the second-floor guard, alerted by the crash, was pointing his pistol at him.

Conspiracy theories are like creepers, Vásquez, they grab on to whatever they can to climb up and keep growing until someone takes away what sustains them.

“Feelings of humiliation, resentment, sexual dissatisfaction, inferiority complexes: there you have the engines of history, my dear patient. Right now someone is making a decision that affects you and me, and they’re making it for reasons like these: to harm an enemy, to get revenge for an affront, to impress a woman and sleep with her. That’s how the world works.”

“A fanatic is a person who’s only good for one thing in this life, who discovers what that thing is and devotes all his time to it, down to the last second. That thing interests him for some special reason. Because he can do something with it, because it helps him to get money, or power, or a woman, or several women, or to feel better with himself, to feed his ego, to earn his path to heaven, to change the world.”

„În politică, nimic nu se petrece întîmplător“... Fraza îi încîntă pe adepții teoriilor conspirative, poate pentru că vine de la un om care de-a lungul timpului a hotărît atît de multe (adică nu a lăsat loc cauzalității sau întîmplării). Dar ceea ce conține în esenţă, dacă te apropii de adîncimile ei fetide, este suficient ca să-l înfricoșeze chiar și pe cel mai curajos dintre noi, pentru că fraza aceasta face praf și pulbere una dintre puținele certitudini pe care ne bazăm viața: că nenorocirile, ororile, durerea și suferința sînt imprevizibile și inevitabile, iar dacă cineva le poate prevedea sau cunoaște va face tot posibilul să le evite” (pp.480-481).

...there are truths that don't happen in those places, truths that nobody writes down because they're invisible. There are millions of things that happen in special places... they are places that are not within the reach of historians or journalists. They are not invented places... they are not fictions, they are very real: as real as anything told in the newspapers. But they don't survive. They stay there, without anybody to tell them.

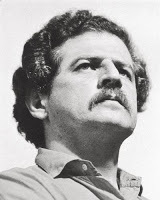

Well, the reason had to do with the circumstances in which the novel was born. I met this surgeon who invited me to his place and showed me the human remains - right? - a vertebra that belonged to Jorge Eliécer Gaitán and then a part of the skull that belonged to Rafael Uribe Uribe. This happened in September of 2005. That was the same moment in my life in which my twin daughters were being born in Colombia - in Bogota. Now, they were born very prematurely - at 6 1/2 months - which is a complicated situation that led to my wife and me spending a lot of time at the hospital while the girls recovered in their incubators.His fictional alter-ego makes a similar point:

I saw myself immersed in this very strange situation in which I went to this guy's place to take in my hands the human remains of two victims of political violence in Colombia, and then I went back to the hospital to take my own girls into my hands.

And the situation was so - so potent with me that these questions began taking shape very slowly in my head. What relationship is there between the two moments? Is my country's violent past, is that transmissible? Will that go down generation after generation to reach, in some way, the lives of these girls that have just been born? How can I protect them from this legacy of violence? I have always been aware that my life has been shaped by the crime of Gaitan for personal reasons, family reasons, sociopolitical reasons. It has shaped my whole country and the life of everybody I know. And so I thought, will that happen to my girls?

And so I realized that inventing a narrator, inventing a personality different from myself would, in a way, diminish them - or rather, undermine the importance these events had for my life. So - making a narrator up would remove me from these events, these anecdotes. And I didn't want that to happen. I wanted to take moral responsibility, as it were, for everything that I was telling in the novel.

(from https://www.npr.org/2018/11/07/665219...)

now it seems incredible that i hadn't understood that our violences are not only the ones we had to experience, but also the others, those that came before, because they are all linked even if the threads that connect them are not visible, because past time is contained within present time, or because the past is our inheritance without the benefit of an inventory and in the end we eventually receive it all: the sense and the excesses, the rights and the wrongs, the innocence and the crimes.juan gabriel vásquez's stirring new novel, the shape of the ruins (la forma de las ruinas), is a work of historical intrigue, conspiracy theory, and the immutable weight of both a country and a family's long legacy. somewhere between a political thriller and a fictionalized autobiographical account, the colombian author's latest book springs from the annals of yesteryear while situating itself in a milieu not dissimilar from what came before (evoking twain's famous line, "history never repeats itself but it rhymes"). the shape of the ruins, first published in spanish in 2015, contends with the dark, violent history of the author's homeland and the political turbulence that has marked so much of its past.

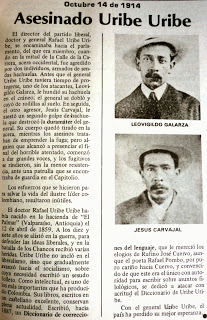

i don't know when i started to realize that my country's past was incomprehensible and obscure to me, a real shadowy terrain, nor can i remember the precise moment when all that i'd believed so trustworthy and predictable—the place i'd grown up, whose language i speak and customs i know, the place whose past i was taught in school and in university, whose present i have become accustomed to interpreting and pretending i understand—began to turn into a place of shadows out of which jumped horrible creatures as soon as we dropped our guard. with time i have come to think that this is the true reason why writers write about the places of childhood and adolescence and even their early youth: you don't write about what you know and understand, and much less do you write because you know and understand, but because you understand that all your knowledge and comprehension is false, a mirage and an illusion, so your book are not, could not be, more than elaborate displays of disorientation: extensive and multifarious declarations of perplexity. all that i thought was so clear, you then think, now turns out to be full of duplicities and hidden intentions, like a friend who betrays us. to that revelation, which is always annoying and often frankly painful, the writer responds in the only way one knows how: with a book. and that's how you try to mitigate your disconcertion, reduce the space between what you don't know and what can be known, and most of all resolve your profound disagreements with that unpredictable reality. "out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric," wrote yeats. "out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry." and what happens when both quarrels arise at the same time, when fighting with the world is a reflection or a transfiguration of the subterranean but constant confrontation you have with yourself? then you write a book like the one i'm writing now, and blindly trust that the book will mean something to somebody else.the shape of the ruins has at its heart the assassinations of two prominent colombian figures: jorge eliécer gaitán (in 1944) and rafael uribe uribe (in 1914). himself a character and part-time narrator in the story, vásquez finds himself embroiled in the past, charged with wading through misinformation and conflicting records, while also contending with a pair of characters whose motivations aren't initially clear. as vásquez digs deeper into the mystery of gaitán's murder (and the possible conspiracy that preceded it and the cover-up that followed), he's forced to reckon with the veracity of colombia's accepted history, while attempting to make sense of a seemingly vanishing veracity.

contact sustained with other people's paranoias, which are multifarious and lie hidden behind the most tranquil personalities, work on us without our noticing, and if you don't watch out, you can end up investing your energy in silly arguments with people who devote their lives to irresponsible conjectures.in our current era of fake news, conspiracy theories, alternative facts, and overall devaluation of truth, vásquez's novel speaks to a moment far greater than the ones from which it sprang. the shape of the ruins has a resonance that transcends both country and century, illuminating the ongoing power struggles that seem to alight on all things political. with his compelling characters and propulsive plot, vásquez's the shape of the ruins is an engaging tale of schemes and machinations. though vásquez's fiction trends toward the conventional, the shape of the ruins is an exquisite exploration of conspiracy, collusion, assassination, and society's shaping forces.

"he understood that, vásquez, he understood that terrible truth: that they were killed by the same people. of course i'm not talking about the same individuals with the same hands, no. i'm talking about a monster, an immortal monster, the monster of many faces and many names who has so often killed and will kill again, because nothing had changed here in centuries of existence and never will change, because this sad country of ours is like a mouse running on a wheel."

"I want to forget this absurd rhetoric of Latin America as a magical or marvelous continent. In my novel, there is a disproportionate reality, but that which is disproportionate in it is the violence and cruelty of our history and of our politics. Let me be clear about this quote, which I suppose refers, in a caringly sarcastic tone, to One Hundred Years of Solitude. I believed that with this novel, and I can say that reading One Hundred Years ... in my adolescence contributed much to my vocation, but I believe that all of the sides of magical realism is the least interesting part of this novel. I propose to read One Hundred Years like a distorted version of Colombian history. That is the interesting part; in what makes One Hundred Years ... with the massacre of the banana workers or the civil wars of the 19th century, not in the yellow butterflies or in the pigs' tails. Like all grand novels, One Hundred Years of Solitude requires us to reinvent the truth. I believe that this reinvention is to make us lose ourselves in magical realism. And what I have tried to make in my novel is to recount the 19th Century Colombian story in a radically distinct key and I fear to oppose what Colombians have read until now.)

“In politics, nothing happens by accident,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said. “If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way.”

"it’s very easy to ignite suspicion but what is necessary is to prove it."

"Many years ago I’d dropped the habit of reading the online comments my column inspired, not only from lack of interest and time, but out of the profound conviction that they displayed the worst vices of our new digital societies: intellectual irresponsibility, proud mediocrity, implausible denigration with impunity, but most of all verbal terrorism, the schoolyard bullying that the participants got involved in with incomprehensible enthusiasm, the cowardice of all those aggressors who used pseudonyms to vilify but would never repeat their insults out loud. The forum of opinion columns has turned into our modern and digital version of the Two Minutes Hate: that ritual in Orwell’s 1984 in which an image of the enemy is projected and the citizens ecstatically give themselves over to physical aggression (they throw things at the screen) and verbal aggression (they insult, shriek, accuse, defame), and then go back to the real world feeling free, unburdened, and self-satisfied."

"maybe because marble plaques are reserved by some implicit or silent tradition for those who drag others to their deaths, those whose unexpected fall can take down a whole society and often does, and that’s why we protect them—and that’s why we fear their deaths. In ancient times no one would have hesitated to give their life for their prince or their king or their queen, for all knew that their downfalls, whether due to madness or conspiracy or suicide, could well push the whole kingdom into the abyss."

“It’s one of two things: either my wife is drowning or we’ve run out of ice.”

"I dislike willful irrationality and I can’t stand people hiding behind language, especially if it involves the thousand and one formulas language has invented to protect our human tendency to believe without proof."

“Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric,” wrote Yeats. “Out of the quarrel with ourselves, we make poetry.”