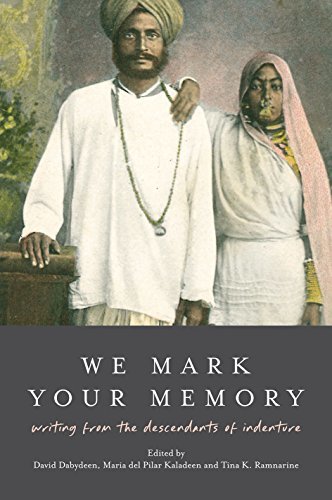

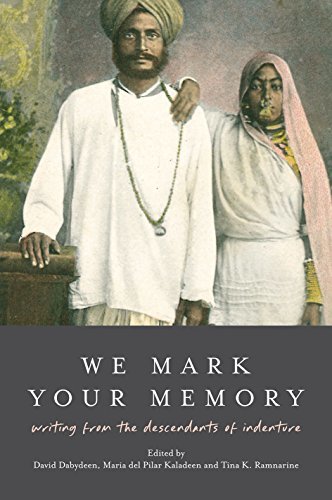

We Mark Your Memory: Writing from the Descendants of Indenture is an anthology edited by David Dabydeen, Maria del Pilar Kaladeen, and Tina K. Ramnarine. It is a collection of poems, stories, and essays that mark the centenary of the abolition of indentured labour in the british empire, and explores indentured heritage in the 21st century. Most of the pieces in this book are about the Indian indentured labour diaspora.

My Indian ancestors were indentured labourers in Guyana. Reading this book was a healing experience because it acknowledges that indenture happened and it gave space for descendants to write about their heritage and identity. Indenture isn't a commonly discussed topic unless it's a part of your heritage. How many of you can say that you knew about the millions of Indian, Chinese, and African people who were coerced into migrating to british colonies, or stolen from their homes, all with false promises of freedom and wealth? Growing up, being a descendant of indenture felt like a secret only my family knew about. In my experience it's rare for someone to understand what being Guyanese really means.

I enjoyed most of the pieces in this book, especially the poems. The poets did an incredible job of capturing different aspects of the indenture experience, as well as what it feels like to be a descendant of indenture. I appreciate how indenture histories were discussed across the world, expanding my understanding of the indenture system and how widespread it was. The essay Tales of the Sea by Gaiutra Bahadur was my favourite.

The existence of this book is an act of resistance. Many records of indentured labourers were destroyed (if records were kept at all), erasing the identities and information about the people who laboured at plantations across the world. This made it easier to forget about indenture and erase these people from history. But the descendants of indenture remember and we carry what little knowledge remains of our ancestor's lives with us.