What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1966

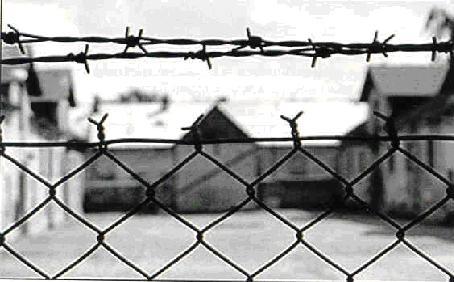

“I did not strive for an explicative account at that time, thirteen years ago, and in the same way now too, I can do no more than give testimony… I had no clarity when I was writing this little book, I do not have it today, and I hope that I never will. Clarification would also amount to disposal, settlement of the case, which can then be placed in the files of history. My book is meant to aid in preventing precisely this. For nothing is resolved, no conflict is settled, no remembering has become a mere memory. What happened, happened. But that it happened cannot be so easily accepted.”

“Whoever was tortured, stays tortured. Torture is ineradicably burned into him, even when no clinically objective traces can be detected… Whoever has succumbed to torture can no longer feel at home in the world.”

When he crossed the border into exile in Belgium, and had to take on himself the Jewish quality of homelessness, of being elsewhere, être ailleurs, he did not yet know how hard it would be to endure the tension between his native land as it became ever more foreign and the land of his foreign exile as it became ever more familiar. Seen in this light, Améry's suicide in Salzburg resolved the insoluble conflict between being both at home and in exile, "entre le foyer et le lontain."

- W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction