What do you think?

Rate this book

160 pages, Paperback

First published March 21, 2017

Lately it’s the round of coughing in the hallway that lets me know he’s home. I go out and meet him, we have a cuddle, and then I look at the Standard while he gets changed. We don’t talk much in the evenings, but we’re very affectionate. When we cuddle on the landing, and later in the kitchen, I make little noises – little comfort noises – at the back of my throat, as does he. When we cuddle in bed at night, he says, ‘I love you so much!’ or ‘You’re such a lovely little person!’ There are pet names, too. I’m ‘little smelly puss’ before a bath, and ‘little cleany puss’ in my towel on the landing after one; in my dungarees I’m ‘you little Herbert!’ and when I first wake up and breathe on him I’m his ‘little compost heap’ or ‘little cabbage’. Edwyn kisses me repeatingly, and with great emphasis, in the morning.

There have been other names, of course.

‘Just so you know,’ he told me last year, ‘I have no plans to spend my life with a shrew. Just so you know that. A fishwife shrew with a face like a fucking arsehole that’s had…green acid shoved up it.’

‘You can always just get out if you find me so contemptible,’ he went on, feet apart, fists clenched, glaring at me over on the settee. ‘You have to get behind the project, Neve, or get out.’

‘What?’

‘Get…behind…the project…or…get out!’

‘What’s “the project”?’

‘The project is not winding me up. The project is not trying to get in my head and make me feel like shit all the time!’

The difference between us, which I did try to keep in mind, was that he really did feel himself under threat back then. He’d had serious heart trouble. An operation. He’d had to lose a lot of weight, stop smoking. Things had settled down by the time we met, but he told me he couldn’t feel safe. Not ever again. He was also starting to suffer terribly with his joints. Fibromyalgia, as we later found out. ‘I’m paying for something,’ he’d snarl, cornered. Or sometimes he’d just sit and sob, and look up at me with frightened eyes when I sat next to him.

I’m not your father. He’s the one you belittled you, all right? That’s what I’m saying. I don’t exist, you don’t hear what I say, what you hear is your father.

…

You read constantly don’t you? Has none of this ever made you consider, or allow, or admit, that people can represent something other than an opponent to you? That people can operate from motives other than wanting to harm you or laugh at you or belittle you.

I’m very glad my mother left my father, of course, but as I got older it did get harder to valorize that flight. This cover-seeking – desparate, adrenalized – had constituted her whole life as far as I could see. In avoidance of any reflection, thought. In which case her leaving him was a result of the same impulse that had her hook up with him in the first place. Not to think, not to connect: marry an insane bully. Simper at him. Not to be killed: get away from him. And her children? Her issue? How did they fit into her scheme? As sandbags? Decoys?

For fifteen years, every Saturday, my brother and I were laid on to service him. To listen to him. To be frightened by him, should he feel like it. As a child with his toys, he exercised a capricious rule, and as with any little imperator, his rage was hellish were his schemes not reverenced.

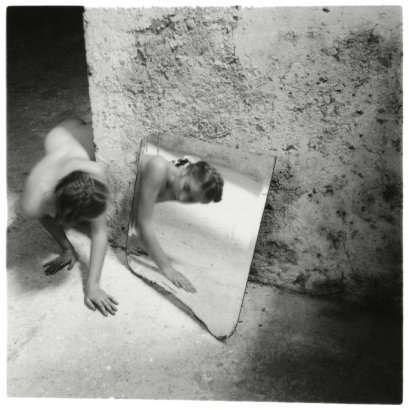

I thought of my mother on the move. The energy for each flight, as for all her lashing out, surely generated by the cowering cringe she lived in. Was I like that? Would I be? I'd hardly been unprone to impulsive moves. Dashes. Surges. The impetus seemed different, but perhaps it amounted to a similar insufficiency.

My father's sprees were both a reaction to and the cause of his confinement. It was his debts which meant he could t move from that house, even when the stairs got to be a daily torture. Was I too stupid - I couldn't be - to take a lesson from that? Could I trust myself? Not to make my life a lair.

I thought of my mother, on the move. The energy for each flight, as for all of her lashing out, surely generated by the cowering cringe she lived in. Was I like that? Would I be? I’d hardly been unprone to impulsive moves. Dashes. Surges. The impetus seemed different, but perhaps it amounted to a similar insufficiency.

My father’s sprees were both a reaction to and the cause of his confinement. It was his debts which meant he couldn’t move from that house, even when the stairs got to be a daily torture. Was I too stupid – I couldn’t be – to take a lesson from that? Could I trust myself? Not to make my life a lair?

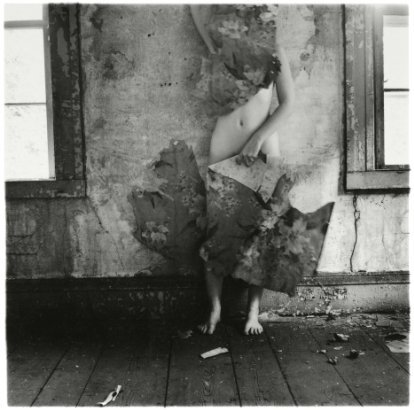

Too often that wretchedness came into me. A torpor. A trance. . And any idea I could do something about it was lost. It’s hard to account for …. but I just felt I had to abide .. Suffer

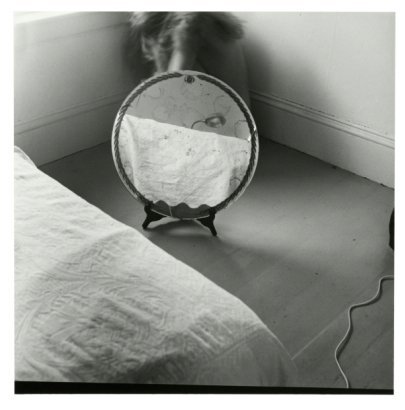

Considering one's life requires a horribly delicate determination, doesn't it? To get to the truth, to the heart of the trouble. You wake and your dreams disband, in a mid-brain void. At the sink, in the street, other shadows crowd in: dim thugs (they are everywhere) who'd like you never to work anything out.

He'd wonder, haltingly, amazedly, at how he'd boxed himself in (ending up with me in his life, he meant), and when he did address me, it was abstractly, with strange conjectures, ruminations, about what I thought, who I was. “I know you hate anyone who didn't grow up on benefits,” he'd say, and if I objected, he'd take no notice, or didn't notice, he only continued, talking over me with mounting scorn: “I know you loathe anyone who didn't grow up in filth, on benefits.” I used to leave my body, in a way, while this went on. It was so incessant, his phrases so concatenated: there was no way in. These were thick, curtain walls. Edwyn has said since that he feels it's me trying to annihilate him. Strange business, isn't it?

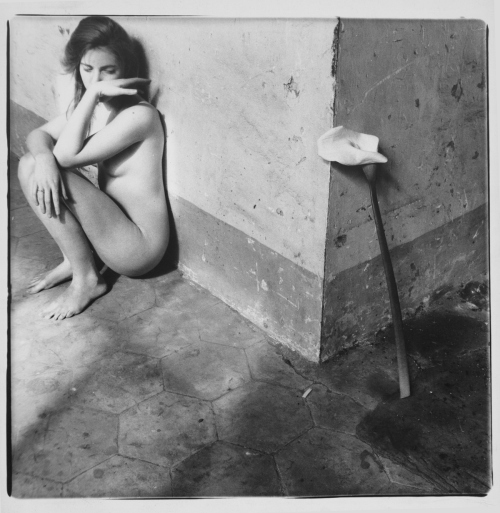

It continued to be frightening, panic-making, to hear the low pleading sounds I'd started making, whenever he was sharp with me. This wasn't how I spoke. (Except it was.) This wasn't me, this crawling, cautious creature. (Except it was.) I defaulted to it very easily. And he let me. Why? I wonder how much he even noticed, hopped up as he was. No, I don't believe he did notice. That was the lesson, I think. That none of this was personal.

It was his whetted look, I found, that I remembered most vividly. His stout expectation. How had that endured: life, knocks? But it had. He was “Just a big kid, really,” Christine said. Well, quite. Somehow he was. A greedy child. A tyrant child. And for fifteen years, every Saturday, my brother and I were laid on service to him. To listen to him. To be frightened by him, should he feel like it. As a child with his toys, he exercised a capricious rule, and as with any little imperator, his rage was hellish when his schemes were not reverenced. One wrong word unlatched a sort of chaos. The look in his eyes then! Licensed hatred. The keenest hunger.

My mother wasn't quite sitting with them, though, but on a low stool a few feet behind Rodger. She wore a familiar expression: too eager, half-sly, while no one spoke to her, or looked at her. She held her empty half-pint glass up by her chin, and grinned hopelessly...It must be a dreadful cross: this hot desire to join in with people who don't want you. The need to burrow in.

Was anybody clean back then? When I think of my friends' houses, they weren't any less filled with shit. Here were cold, cluttered bedrooms, greased sheets. The kitchens were a horror show: ceilings bejewelled with pus-coloured animal fat, washing-up sitting in water which was spangled like phlegm. Our neighbour's house, where we went after school, was an airlocked chamber smelling of bins that hadn't been put out. There was a long skid-mark, I remember, on one of the towels in their bathroom. It was there for three years. So – I did grow up in shit. It was no slander. Shit, filth, stupidity, dishonesty. (Mother looking up slyly from a crying jag.)

Old ladies do just stop bothering, I'm afraid. No husband anymore, no kids, they just decide to live in filth. Stop cleaning the house, stop keeping themselves clean. Or feeding themselves properly. My mother was the same. She'd just eat white bread and jam, unless I went round and cooked for her. So she held that over me. And she started drinking, of course. She could get out to go to the pub all right, with her mad neighbour. Christ, I hated him. Always appearing over the fence. I mean, she made me hate her, really. She made me despise her. Isn't that dreadful? What did she want, really? A bit of attention.

“An illusion of freedom: snap-twist getaways with no plans: nothing real. I’d gven my freedom away. Time and again. As if I had contempt for it. Or was it hopelessness I felt, that I was so negligent? Or did it hardly matter, in fact?”

“Could I trust myself? Not to make my life a lair.”