"Man's love is of his life a thing apart, 'Tis woman's whole existence. Man may range the court, camp, church, the vessel, and the mart; sword, gown, gain, glory offer in exchange pride, fame, ambition to fill up his heart, and few there are whom these cannot estrange. Man has all these resources, we but one, to mourn alone the love which has undone." (Canto I, Stanza 194)

"There still are many rainbows in your sky, but mine have vanished. All, when life is new, commence with feelings warm and prospects high; but time strips our illusions of their hue, and one by one in turn, some grand mistake casts off its bright skin yearly like the snake." (Canto V, Stanza 21)

"But these are foolish things to all the wise, And I love wisdom more than she loves me; My tendency is to philosophise On most things, from a tyrant to a tree; But still the spouseless virgin Knowledge flies. What are we? and whence came we? what shall be Our ultimate existence? what's our present? Are questions answerless, and yet incessant." (Canto VI, Stanza 63)

"O Love! O Glory! what are ye who fly Around us ever, rarely to alight? There's not a meteor in the polar sky Of such transcendent and more fleeting flight. Chill, and chain'd to cold earth, we lift on high Our eyes in search of either lovely light;

A thousand and a thousand colours they Assume, then leave us on our freezing way.

And such as they are, such my present tale is,A non-descript and ever-varying rhyme, A versified Aurora Borealis,

Which flashes o'er a waste and icy clime. When we know what all are, we must bewail us, But ne'ertheless I hope it is no crime

To laugh at all things -- for I wish to know What, after all, are all things -- but a show?" (Canto VII, Stanzas 1-2)

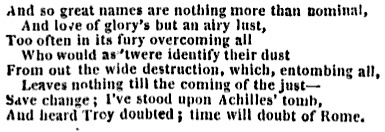

Above are written some of the most striking lines inscribed in Lord Byron's magnum opus Don Juan, the greatest epic in the English language composed since Milton's Paradise Lost. In grand contrast, however, to Milton's Biblically-inspired work set out to "justify the ways of God to man", Lord George Gordon Byron, in his characteristically hedonistic and sensual style, gives us the unfinished tales in verse of Don Juan to achieve a different feat, perhaps more like a reverse of Milton's ambition, in justifying the ways of man to God. Byron, who was one of the finest poets of the British Romantic period, certainly possessed more than the other Romantics the sensational personality and temperament that typifies the Romantic soul. He attained notoriety in his lifetime for what was perceived as a scandalous and decadent lifestyle, marred by a multitude of love affairs and self-exile from England, drenched in the lavish nectar pools of revelry and consumed by a restless spirit of adventure. His poetry, which is definitely the most crisp and accessible of the Romantics I think, is always seething with an impassioned energy and insatiable vitality, and no where are these qualities invested with more zeal and zest than in the verses of Don Juan. In his epic Byron fleshes out for us the figure of Don Juan, who is a perfect alter-ego for Byron and the consummate incarnate of the so-called Byronic hero: lifted from the legend of the unfettered libertine who seduced, inflamed and then broke the hearts of many a damsel until finally cast into Hell to face eternal retribution for his indecorous life of crime. In this tale however, Don Juan is spiced up and modified in Byron's own flavor. Rather than a heartless rake who ravishes one woman after the other without remorse, Byron's Don Juan is a sympathetic figure who is thrown into a series of larger-than-life misfortunes that pave the adventurous path from one tribulation to the next. The plot itself that propels this tale is fascinating on its own: Don Juan's endless escapades and perils that stem from a single love affair in Spain that ends up being exposed in delicto flagrante to an angry husband, sending him into a sea-borne escape that ends in shipwrecks, delivering him to a remote Mediterranean island where he's a rescued by a voluptuous Greek maiden whose father is a pirate who makes Don Juan a prisoner to in turn be sold to the Turkish sultan, followed by more love affairs, a grandiose battle scene of Homeric scale, moving on to Russia and the Tsarina Catherine the Great and then to Byron's homeland England where sadly the story ends abruptly without closure. I can avow that in the 17 stunning cantos of Don Juan, this lack of finality is the only real disappointment. The stanzas running through the pages simply effervesce with feverish rapture, eloquent paeans of passion, piercing wit, and a subtle humor that could only spring from the inimitable voice of Lord Byron. Besides the unbounded riots of adventure in the story of Don Juan, what is sometimes even more notable are Byron's social commentaries that saturate his verse, often with vitriol, measured contempt, and even smug certitude in his free-thinking ways, but always with wonderful craftsmanship and extremely witty acuity. Byron's frequent digressions often take aim at his contemporaries such as Southey and Wordsworth, whose styles he rejected, as well as many other observations that express Byron's rather cynical worldview and opinions, that in his own day, would be deemed unorthodox or heretical to the mores of the British society. Every subject is fair game for Byron, whether it's the differing sensibilities between men and women, love, religion, philosophy, history, war, politics, social etiquette, etc. One notable line that so well articulates Byron's viewpoint is in Canto IV, Stanza 101: "And so great names are nothing more than nominal, and love of glory's but an airy lust, too often in its fury overcoming all who would 'twere identify their dust from out the wide destruction, which entombing all, leaves nothing 'till the coming of the just', save change. I've stood upon Achilles' tomb and heard Troy doubted; time will doubt of Rome." And there's so many more... In truth, Byron's masterpiece is a veritable treasure-trove of knowledge and enriching lyricism that gushes with emotional electricity traversing the whole spectrum. On a final note, I'd like to quote my own personal favorite description from the epic poem, from the last completed canto, Canto XVI, in which Byron conjures up a ghostly specter, the haunting Blackfriar, with deliciously Gothic gloom that I savor so much.

(Canto XVII, Stanza XIV-21)

XIV

But lover, poet, or astronomer,

Shepherd, or swain, whoever may behold,

Feel some abstraction when they gaze on her:

Great thoughts we catch from thence (besides a cold

Sometimes, unless my feelings rather err);

Deep secrets to her rolling light are told;

The ocean's tides and mortals' brains she sways,

And also hearts, if there be truth in lays.

XV

Juan felt somewhat pensive, and disposed

For contemplation rather than his pillow:

The Gothic chamber, where he was enclosed,

Let in the rippling sound of the lake's billow,

With all the mystery by midnight caused;

Below his window waved (of course) a willow;

And he stood gazing out on the cascade

That flash'd and after darken'd in the shade.

XVI

Upon his table or his toilet, -- which

Of these is not exactly ascertain'd

(I state this, for I am cautious to a pitch

Of nicety, where a fact is to be gain'd), --

A lamp burn'd high, while he leant from a niche,

Where many a Gothic ornament remain'd,

In chisell'd stone and painted glass, and all

That time has left our fathers of their hall.

XVII

Then, as the night was clear though cold, he threw

His chamber door wide open -- and went forth

Into a gallery, of a sombre hue,

Long, furnish'd with old pictures of great worth,

Of knights and dames heroic and chaste too,

As doubtless should be people of high birth.

But by dim lights the portraits of the dead

Have something ghastly, desolate, and dread.

XVIII

The forms of the grim knight and pictured saint

Look living in the moon; and as you turn

Backward and forward to the echoes faint

Of your own footsteps -- voices from the urn

Appear to wake, and shadows wild and quaint

Start from the frames which fence their aspects stern,

As if to ask how you can dare to keep

A vigil there, where all but death should sleep.

XIX

And the pale smile of beauties in the grave,

The charms of other days, in starlight gleams,

Glimmer on high; their buried locks still wave

Along the canvas; their eyes glance like dreams

On ours, or spars within some dusky cave,

But death is imaged in their shadowy beams.

A picture is the past; even ere its frame

Be gilt, who sate hath ceased to be the same.

XX

As Juan mused on mutability,

Or on his mistress -- terms synonymous --

No sound except the echo of his sigh

Or step ran sadly through that antique house;

When suddenly he heard, or thought so, nigh,

A supernatural agent -- or a mouse,

Whose little nibbling rustle will embarrass

Most people as it plays along the arras.

XXI

It was no mouse, but lo! a monk, array'd

In cowl and beads and dusky garb, appear'd,

Now in the moonlight, and now lapsed in shade,

With steps that trod as heavy, yet unheard;

His garments only a slight murmur made;

He moved as shadowy as the sisters weird,

But slowly; and as he pass'd Juan by,

Glanced, without pausing, on him a bright eye.