What do you think?

Rate this book

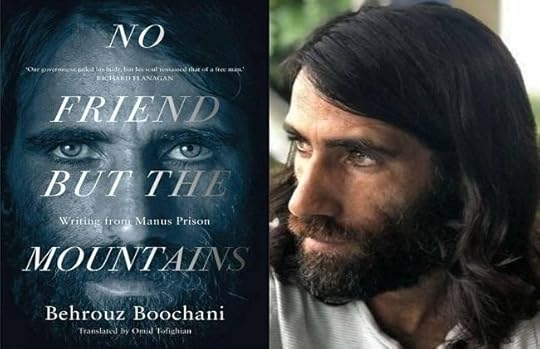

417 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2018

“Can it be that I sought asylum in Australia only to be exiled to a place I know nothing about? And are they forcing me to live here without any other options? I am prepared to be put on a boat back to Indonesia; I mean, the same place I embarked from. But I can’t find any answers to these questions.

Clearly, they are taking us hostage. We are hostages – we are being made examples to strike fear into others, to scare people so they won’t come to Australia.

What do other people’s plans to come to Australia have to do with me? Why do I have to be punished for what others might do?”

When humans struggle over territory /

It always reeks of violence and bloodshed /

Even if the conflict is over a location the size of one body /

On a small boat /

And only for a period of two days.