What do you think?

Rate this book

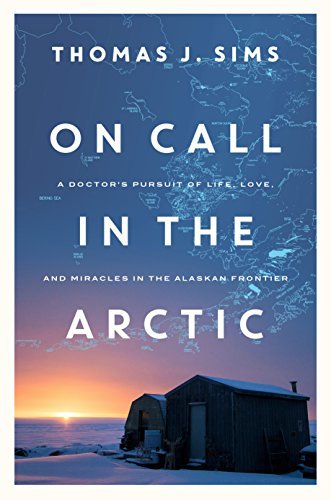

An extraordinary memoir recounting the adventures of a young doctor stationed in the Alaskan bush.

The fish-out-of-water stories of Northern Exposure and Doc Martin meet the rough-and-rugged setting of The Discovery Channel’s Alaskan Bush People in Thomas J. Sims’s On Call in the Arctic, where the author relates his incredible experience saving lives in one of the most remote outposts in North America.

Imagine a young doctor, trained in the latest medical knowledge and state-of-the-art equipment, suddenly transported back to one of the world’s most isolated and unforgiving environments—Nome, Alaska. Dr. Sims’ plans to become a pediatric surgeon drastically changed when, on the eve of being drafted into the Army to serve as a M.A.S.H. surgeon in Vietnam, he was offered a commission in the U.S. Public Health for assignment in Anchorage, Alaska.

In Anchorage, Dr. Sims was scheduled to act as Chief of Pediatrics at the Alaska Native Medical Center. Life changed, along with his military orders, when he learned he was being transferred from Anchorage to work as the only physician in Nome. There, he would have the awesome responsibility of rendering medical care under archaic conditions to the population of this frontier town plus thirteen Eskimo villages in the surrounding Norton Sound area. And he would do it alone with little help and support. All the while, he was pegged as both an “outsider” and an employee of the much-derided federal government.

In order to do his job, Dr. Sims had to overcome racism, cultural prejudices, and hostility from those who would like to see him sent packing. On Call in the Arctic reveals the thrills and the terrors of frontier medicine, where Dr. Sims must rely upon his instincts, improvise, and persevere against all odds in order to help his patients on the icy shores of the Bering Sea.

333 pages, Kindle Edition

First published September 4, 2018

"No knowledge is ever wasted."

"When faced with difficult decisions in the future, I would tally up my intellect and emotions and allow my heart equal influence with my head before deciding how to act. I learned that more than likely, whichever way my heart leaned is probably the way I should proceed."

Our first impression was that Nome was a shantytown; a settlement of tiny houses built of plywood and corrugated metal, lined up door to door on streets made of matted down dirt and gravel. There was no landscaping around the houses because there were no yards to accommodate landscaping. There were no services such as water or sewers, streetlights, telephones, curbs, or sidewalks, and nothing to give the town personality. Everything was build from a functional standpoint to get through the brutal harshness of winter. Survival was the only concern; aesthetics mattered little. (70)But in other ways, it sounds like there were some similarities. Sims was the sole doctor on hand in Nome (on call 24/7, in addition to his daily working hours) and was also responsible for care in the outlying villages, many of which comprised little more than a cluster of shanties. Take this observation when he was called out for a tricky birth:

I made a mental inventory of what I had and what I didn’t.

Obviously, there was plenty I needed: anesthesia; scalpels; suture material; an umbilical cord clip; sterile surgical instruments; forceps, needles and syringes; dressings; IV fluids; medications to stop bleeding; oxygen; isolette for the newborn; diapers. All the normal things a hospital supplies for mothers about to have a child.

What I had was: two pairs of sterile gloves; Betadine soap; a bundle of Band-Aids held together by a rubber band; a couple of syringes, but no helpful medicines to use with them; scissors that were not sterilized; and my stethoscope. It was an “up shit creek without a paddle” scenario and I knew it. (194)This is the sort of medicine that requires constant outside-the-box thinking: a little bit of everything and whole lot of sink-or-swim.