What do you think?

Rate this book

264 pages, Hardcover

First published April 9, 2019

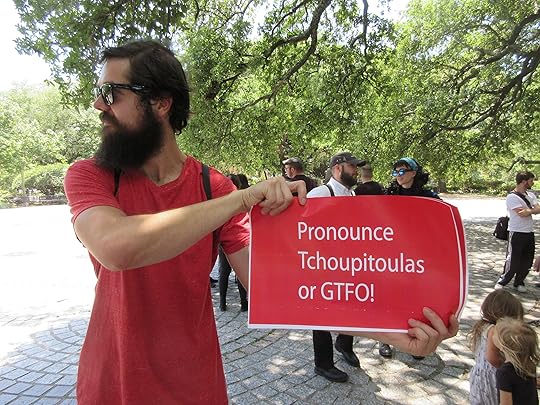

a bus was boarded by armed men, one of whom held a tomato and demanded each passenger tell him what it was: those who said it was a ‘banadura’, identifying themselves as Lebanese, were ordered off the bus; those who called it a ‘bandura’, revealing themselves to be Palestinians, remained on the bus and were slaughtered.

They could say ‘se me rompió’, which can only be translated nonsensically or awkwardly in English: ‘it broke to me’, ‘to me it happened that it broke’.

Britain, speaking English and only English, based its decisions on emotions and found itself in disarray. The twenty-seven countries on the other side, speaking English among themselves, achieved a remarkable degree of coherence, based on a clear understanding of their collective interests.

Finding paths through language territories may not require maps, but it does require guiding principles. This book follows several; one is that paths are worth finding. The use of more than one language is a good thing: not always, not necessarily, not inherently, but in most circumstances and in spirit, it is good. There are many reasons for this, but the underlying one is that it favours a complex of goods: openness, interconnection, inclusion, mutual exchange and the sharing of knowledge.

Another is that the two-sided character of language must always be recognised. It is the place from which the path has to start. We will get hopelessly lost if we lose sight of the truth that language exists as much to prevent communication as to make it happen. This is not really a paradox: the design logic of enabling information to circulate within a group, while restricting its ability to enter or leave, is all too easy to grasp. There you have it: the two sides of human nature, inward community and outward exclusion, the latter the engine of the former. Sympathy is generated by drawing limits around it. To transcend this design, to liberate those better angels of our nature, we need to treat the dual character of language as a contradiction that must be resolved, or at least mitigated.

The third basic principle, that all of a person’s linguistic resources should be valued, helps to ease the conflict. Under this principle, languages are treated with due respect, but not with undue deference. A language is regarded not as an edifice within which a community is housed and to which individuals may aspire to gain admission, but as an assembly of elements which individuals are free to use as they wish. This does not mean that maintaining its integrity and sustaining its vitality are unimportant. Quite the reverse: the better shape a language is in, the more use its elements will be. A healthy language will keep its identity while encouraging a rich variety of relationships to flourish across its boundaries, in different combinations, balances, modes and registers, at different levels of proficiency. Its perimeter will not be a dumb fence; it will be a complex and productive interface, like the membrane of a living cell. Yet the key to this complexity is the simple principle that we should make the most of whatever we can grasp. It is a practical, everyday way to reduce the inherent tensions of language use.

The first steps are simple too. Make what you can of the words you hear and see, spoken, written or signed. Start speaking, and keep going.

It took Sümeyra Tosun a while to work out why she felt there was something wrong when she spoke English. [...]

Eventually she realised what it was. Turkish obliges its speakers to specify whether information is first-hand or not, by attaching suffixes to the end of verbs: di or variants thereof for first-hand information, miş or variations of it for information that is not first-hand. Tosun had never paid any mind to this grammatical requirement before, but when she ventured into a language that lacked it, she felt its absence as unease.

Rules and social norms are embedded in native languages. If people are disconnected from their mother tongues, they may be disconnected from channels to personal memories that are the source of powerful sentiments about right and wrong. [...]

These researchers also remarked on the possible importance of the 'foreign language effect' in international bodies such as the United Nations and European Union. Discussions within such organisations are generally conducted in a lingua franca, usually English. Most participants will therefore be speaking a language foreign to them, and so may be less strongly in touch with their moral sentiments than they otherwise would. They will also be professionally skilled in rational calculation. The result may be to make international co-operation somewhat more utilitarian than national endeavours. This hypothesis offers a compelling explanation (though far from the only one) for a phenomenon subsequently observed as the United Kingdom negotiated its exit from the European Union. Britain, speaking English and English, based its decisions on emotions and found itself in disarray. The twenty-seven countries on the other side, speaking English amongst themselves, achieved a remarkable degree of coherence, based on a clear understanding of their collective interests.