What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published May 2, 2017

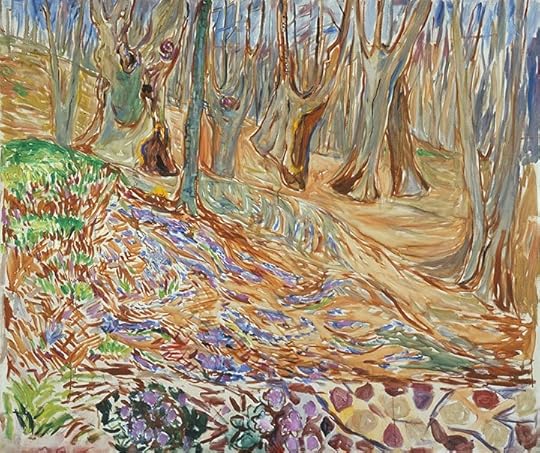

Die Kunst zu malen, besteht darin zu sehen und dann den Abstand zwischen dem Gesehenen und dem Gemalten möglichst klein zu machen. Munchs große Begabung bestand in seiner Fähigkeit, nicht nur zu malen, was der Blick sah, sondern auch das, was in ihm lag.