What do you think?

Rate this book

184 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2008

Dar means land. The Fur are tribespeople farther south who are mostly farmers. One of the Fur leaders was king of the whole region in the 1500s. The region took its name from that time. [p.x]

As for the future, the only way that the world can say no to genocide is to make sure that the people of Darfur are returned to their homes and given protection. If the world allows the people of Darfur to be removed forever from their land and their way of life, then genocide will happen elsewhere because it will be seen as something that works. It must not be allowed to work. The people of Darfur need to go home now. [p.x]

You have to be stronger than your fears if you want to get anything done in this life. [p.11]

"Shooting people doesn't make you a man, Daoud," [Ahmed] said. "Doing the right thing for who you are makes you a man." [p.17]

It says everything about this land to know that even the mountains are not to be trusted, and that the crunching sound under your camel's hooves is usually human bones hidden and revealed as the wind pleases. [p.20]

In Africa, our families are everything. We do all we can to help them, without question. [p.23]

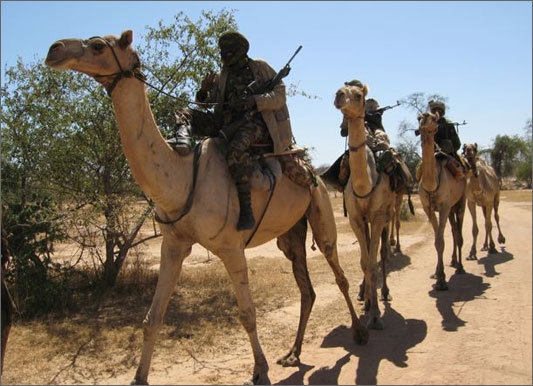

Many men were joining resistance groups; you would see very young teenage boys jumping into the backs of trucks with a family weapon and that was it for them. No one in the boys' families would try to stop them. It was as if everybody had accepted that we were all going to die, and it was for each to decide how they wanted to go. It was like that. The end of the world was upon us. [p.46]

We came upon a lone tree not far from the Chad border where a woman and two of her three children were dead. The third child died in our arms. The skin of these little children was like delicate brown paper, so wrinkled. You have see pictures of children who are dying of hunger and thirst, their little bones showing and their heads so big against their withered bodies. You will think this takes a long time to happen to a child, but it takes only a few days. It breaks your heart to see, just as it breaks a mother's heart to see. This woman hanged herself from her shawl, tied in the tree. We gently took her down and buried her beside her children. This moment stays with me every day. [p.65]

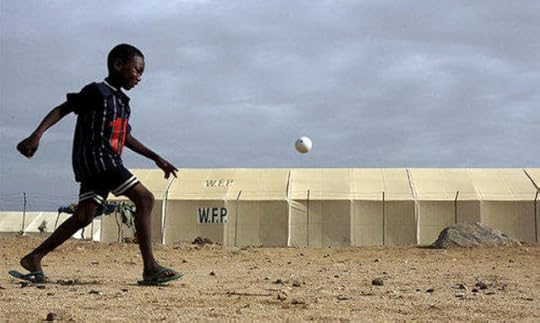

...the world's charity seemed almost invisible here [at the refugee camp]. Perhaps the wealthy nations had finally blown themselves away and were no longer available to send their usual token remedies for the problems that their thirst for resources has always brought to such people as these. [pp.73-4]

At the edge of one village, in a thickly forested place, the village defenders had made their last stand by wedging themselves high in the trees with their rifles. They were all shot and killed. It had been three days or more since the men in the trees had died, and on this steamy spring afternoon, their bodies were coming to earth. We walked through a strange world of occasionally falling human limbs and heads. a leg fell near me. A head thumped to the ground farther away. Horrible smells filled the grove like poision gas that even hurts the eyes. And yet this was but the welcome to what we would eventually see: eighty-one men and boys fallen across one another, hacked and stabbed to death in that same attack.

Reporters are so very human, wonderfully so, and they weep sometimes as they walk through hard areas. There is no hiding their crying after a time. They sometimes kneel and put their heads in their hands near the ground. They pray aloud and will often find A handful of soil to lay on the body of a child, or they may find some cloth to cover the dead faces of a young family - faces frozen in terror with their eyes and mouths still open too wide. They will help bury bodies; we buried many on the British TV journey. But these eighty-one boys and men were too much for everyone. [p.112]

"Did you know that Darfur was a great country long ago, so great that it was both in Sudan and also in Chad? Did you know that the French, who later controlled Chad, and the British, who later controlled Sudan, drew a line, putting half of Darfur in each new nation? Did you know that? What do you care about this line if you are Darfur men? What business is it of yours if the British and the French draw lines on maps? What does it have to do with the fact that we are brothers?" [p.138]

With the mandate of the United Nations, the African Union troops were in Darfur - some barely a mile away - to monitor the peace agreement between the Sudan government and one of the rebel groups. If the government and this rebel group want to attack villages together, or the government and the Janjaweed want to attack a village, or just the Janjaweed or just the government, then that is not the A.U.'s business, though they might make a report about it. They have not been given the resources to do much more than give President Bashir the ability to say that peacekeeping troops are already in Darfur, so other nations can please stay away. Also, African troops have seen so much blood and so many killed that their sense of outrage has perhaps been damaged for this kind of situation. U.N. troops from safer parts of the world, where people still feel outrage, might be better. [pp.146-7]