With Roosevelt and Lindbergh setting the tone, the debate over American’s involvement in the war grew ever more poisonous. “Individuals on both sides found it increasingly difficult to see their opponents as honest people who happened to hold different opinions,” the historian Wayne Cole observed. “Attacks on both sides became more personal, vicious, and destructive. It became easier to see one’s adversaries not just as mistaken but as evil, and possibly motivated by selfish, antidemocratic, or even subversive considerations.” (p. 329)

We’ve been here before. The contemptuous disdain for opposing political views which started on talk radio and Fox News, oozed into Congress and the conservative electorate, and then spread to progressives as a mirror image response, is not something unique to our own times. The good news is that history shows it can be overcome; the bad news is that it took an existential threat to bring people together again. Absent that, the country faces an uncertain future.

This book addresses a period in American history that few people know much about. Some are aware that famed aviator Charles Lindbergh opposed U.S. efforts to provide aid to Britain when it stood alone against Germany after the fall of France, but most history books rush straight from the Great Depression to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Throughout the late 1930s arguments for and against involvement in Britain’s defense polarized the country into hostile camps, each claiming to represent the nation’s real best interests.

At the heart of the conflict were Lindburgh, the arch-isolationist, and President Franklin Roosevelt, who believed that even though the U.S. was itself militarily weak, it must support Britain because if it fell Germany would control all of Europe and the the vital sea lanes needed for American imports and exports, and the way would be open invasion via landings in South America that pushed north through Mexico and into the U.S.

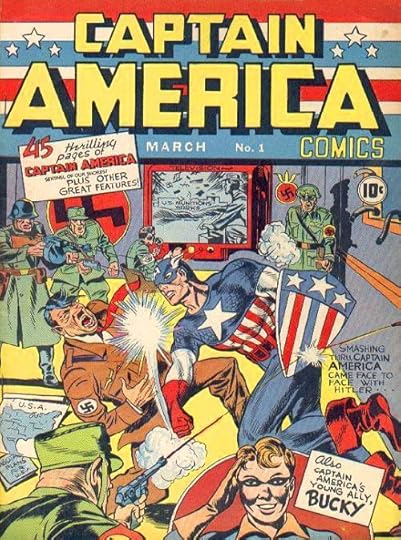

Initially, most Americans were staunch isolationists who wanted nothing to do with Europe. During the First World War British propaganda had free reign to write anything, no matter how outrageous, that would increase Americans’ willingness to join the war and fight. As a result the U.S. was flooded with stories of crucified nuns, bayoneted babies, and all manner of gruesomely outlandish tales presented as completely true. Afterwards it was found to have been lies, and Americans resented being manipulated and misled. When it became clear from the peace negotiations that it had not been the War to End All Wars, and that things would go back to business as usual, people started asking who had benefited from the loss of one hundred thousand American lives, and decided it was the Wall Street bankers and the arms merchants who, given the chance, would do it all over again in the next war. A 1937 Gallup poll found that 70 percent of Americans thought it had been a mistake to enter World War I.

Another consequence of First World War propaganda was that people stopped believing reports of atrocities. First-hand accounts of Jews being imprisoned, tortured, and murdered in German concentration camps were dismissed with a ‘here we go again’ shrug, as were stories out of the Soviet Union of millions dead of starvation in Ukraine, and millions more arrested and sent to the Gulag.

The peace treaty had required Germany to accept full responsibility for starting the war, so it was in their interest to present themselves as having been just another player in the Game of Nations, like France, Britain, and Russia, who had miscalculated and blundered into the conflict. If all the major combatants were equally responsible, Germany could present itself as the victim of the peace negotiations, forced to accept unduly harsh terms by vengeful France and Britain. This argument was accepted by many Americans who were already wary of their former allies, and reinforced their belief that the next war was none of their business.

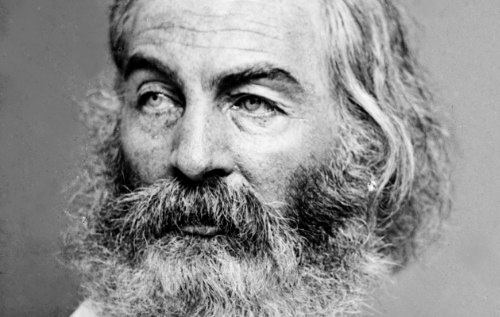

Charles Lindbergh was honorable and incorruptible, but inflexible and incapable of changing his opinions once they had been formed. His wife, the poet and novelist Anne Lindbergh, wrote that there were two ways to do anything, the Lindbergh way, and the wrong way. He made inspection tours in Europe and came to the conclusion that Germany was so far ahead of France and Britain militarily that it would be foolish for them to even attempt another war, and that the United States should by no means take part.

He spoke what he considered the truth courageously and despite any and all opposition, and his fame from his 1927 solo crossing of the Atlantic made him the only person in the country whose popularity could match that of the President. Even when that popularity was shredded as isolationism faded and he was beset by accusations of treason and complicity he never wavered in his positions. He always claimed to be neutral, but the only combatant nation he ever criticized was Britain, never Germany. After the war, when the full extent of Nazi atrocities became clear, he never explained his position or apologized for his support of Hitler’s regime.

Roosevelt comes across poorly in this account. He had been an energetic leader early in his presidency, pushing through the New Deal and showing dynamism and creativity in finding solutions. By the late 30s, however, he had suffered two stinging legislative defeats: his attempt to increase the size of the Supreme Court so that he could appoint judges who would swing the balance of court decisions in his favor, and a disastrous effort to get politicians hostile to his programs voted out, only to find almost all of them returned to office and even more implacable in their hostility to him.

He seemed tired and depressed, refusing to campaign for the nomination for a third term, and then refusing to do any campaigning in the general election until the last month when his opponent had pulled even with him in the polls. The opponent was Republican Wendell Wilkie, hated by his party’s Old Guard and nominated only because of a grass roots revolution at the convention. Wilkie was intelligent, articulate, and like Roosevelt in favor of intervention to support Britain. FDR eventually won the general election because many Americans thought that his experience in international affairs would be crucial in the coming years, but until Pearl Harbor he was so vacillating and ineffectual that Wilkie probably would have been better for the country.

Roosevelt’s lack of action frustrated and angered his advisors. After pushing through the Destroyers-for-Bases agreement and later Lend-Lease, he did nothing. He would not lead, and waited for public opinion polls to tell him which way to lean. Britain, meanwhile, was close to collapse as German U-boats strangled the economy and food rationing was down to almost starvation levels.

It would take a long time for the U.S. to produce enough war material to have measurable effects on the conflict, but in the meantime the civilian economy was booming, and since war production had no special call on resources, even when manufacturers wanted to help many of them could not get enough raw materials. One thing which would have helped immediately, however, would have been for the U.S. Navy to provide escorts for British convoys all the way across the Atlantic. Roosevelt rejected this, however, because inevitably it would have led to combat with German submarines, which would push the country one step closer to war. His advisors reminded him that with Lend-Lease the U.S. was already firmly committed to Britain, and might as well be openly at war, so there was no point in hanging back, but he refused to listen, instead asking for only minor changes to the Neutrality Act, such as allowing merchant ships to arm themselves.

It did not help that most of the top echelon of the U.S. military was firmly in the Isolationist camp. They did not think that Britain was going to survive, so sending tanks, planes, and ships only meant they would be captured by the Germans. To make matters worse they accepted Germany’s wildly inflated estimates of British planes shot down, factories destroyed, and ships sunk, which made them even more pessimistic about providing aid which might soon be needed for the defense of the United States.

The only hero in this odd tale is Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War. Seventy-three years old in 1940, utterly fearless, and by far the most respected member of Roosevelt’s cabinet. He clearly understood the larger issues and articulated the arguments for intervention, and told the President exactly what needed to be done, but even he could not force action from someone determined not to act.

Roosevelt believed that most Americans still wanted to keep out of the war, and he was determined to stay safely within the bounds of opinion polls. He had promised Churchill that he would take decisive action if the German U-boats attacked U.S. Navy ships, but then the USS Kearney was torpedoed with the loss of eleven American seaman, and the USS Reuben James was sunk with one hundred officers and men. Roosevelt did nothing but condemn the attacks.

The book raises two fascinating what-might-have-been scenarios, which would have greatly changed the course of World War II. First, what if the Japanese had not not attacked Pearl Harbor, but instead had gone after British, French, and Dutch possessions? Given Roosevelt’s inaction, the United States would almost certainly have remained neutral, leaving Britain to fight an impossible two-front war.

Second, German, Italy, and Japan had entered into a military alliance, but it only required the other members to act if one of them was attacked. Japan was the attacker at Pearl Harbor, so the other members were not required to join in, and yet Hitler immediately declared war on the United States, bringing it fully into the conflict. By that time Hitler had lost the Battle of Britain and was preparing to invade Russia, but if he had not declared war the Americans almost certainly have decided they must defeat Japan before turning their attention to Europe, and by then the Russian juggernaut may have pushed so far west that the Iron Curtain dropped not on the Elbe, but on the Rhine, possibly at Calais, and all of continental Europe would have fallen under communist domination.

Once war was declared isolationist sentiment dissolved immediately, and the country united in an all-out push for victory. Lindbergh, who had resigned his reserve commission after criticism by Roosevelt, asked to have it reinstated but was refused. He instead worked as a consultant for Henry Ford, who was powerful enough not to care what the President thought, and was quietly allowed to go the Pacific theater. He made some good suggestions for improving the range and performance of American planes, and secretly flew fifty combat missions in Army, Navy, and Marine fighters, shooting down one Japanese Zero.

There is also a strange coda to Lindbergh’s life. After the war he spent most of his time traveling, but when home he ruled the household with iron discipline, and instilled in his children the idea that they must always, always, behave decently and ethically. Lindbergh himself, however, secretly fathered seven additional children by three women in Europe, so the rules he thought were important to others apparently didn’t apply to him.

This is an excellent history book. Although it revolves around Roosevelt and Lindbergh, it takes the time to introduce all the key figures and discuss the events which set public opinion in motion one way or the other. The reader gains an understanding of the zeitgeist of the times, and the viewpoints of both Isolationists and Interventionists are given balanced treatment. The country practically tore itself apart during those angry days, a cautionary tale for America today, and a history that is worth remembering.