An Exegesis on Divine Darkness.

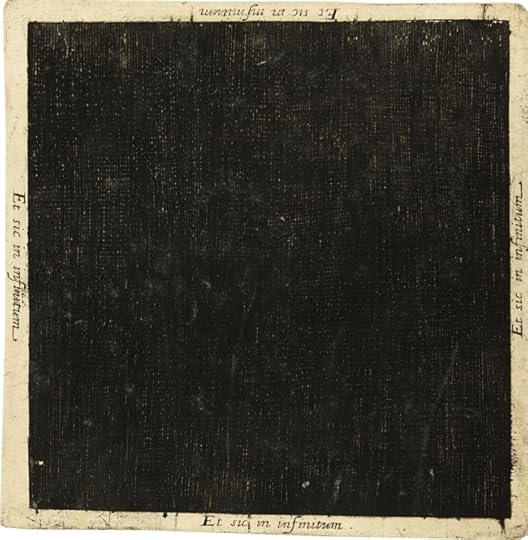

Here we can pause a bit and attempt a summary of the ground we’ve covered thus far. In thinking about darkness (that which “is” and “is not”), we see mystical thinkers connecting a logic (in particular, a logic of negation) with a poetics (a poetics of darkness, shadow, abyss, and the like). With Dionysius the Areopagite the logic of the via negativa is tied to his notion of divine darkness (Θειου σκοτους ακτινα). With Meister Eckhart, a logic of negating negations (negatio negationis) is tied to the darkness (finsternis) of the Godhead, something echoed in the corporeal negations of Angela of Foligno, and the emphasis in The Cloud of Unknowing on a paradoxical contemplation of which cannot be thought. In John of the Cross, a negation of all possible experience (including that of darkness) is tied to this central poetic motif of the dark night (la noche oscura). And finally, in Bataille, a complex logic of excess and leads to what he terms the excess of darkness (l’excès des ténèbres).

What should we make of this tradition of darkness-mysticism. Even though each of these thinkers uses slightly different terms, I would suggest that there are three basic modes of darkness in this mystical tradition: a dialectical darkness, a superlative darkness, and what I’ve been calling a divine darkness.

The first mode – dialectical darkness – entails a concept of darkness that is inseparable from an opposing term, whatever that term may be. Dialectical darkness is therefore structured around the dyad of dark/light, which finds its avatars in the epistemological dyad of knowledge/ignorance, the metaphysical dyad of presence/absence, and the theological dyad of gift/privation. Dialectical darkness always subsumes darkness within its opposing term, and in this sense, darkness is always subordinate to something that opposes or comes after darkness. With dialectical darkness, the movement is from a negative to an affirmative experience of the divine, from the absence of any experience at all to a fully present experience. However, at the same time, this affirmative experience comes at the cost of a surreptitious negation: a “vision” (visio) that is also blindness, an ecstasy (ecstasis) or standing outside oneself that displaces the subject, and a rapture (raptus) in which the self is snatched away into a liminal otherness. We should note that the recuperative power of dialectical darkness is such that it inhabits all attempts to think a concept of darkness – even those that claim to pass beyond oppositions. Dialectical darkness is at once the ground of, and the obstacle for, any concept of darkness.

This management of boundaries shifts a bit when we move to superlative darkness, the second mode. Superlative darkness is a darkness precisely because it lies beyond the dialectical opposition of dark and light. Paradoxically, superlative darkness surpasses all attempts to directly or affirmatively know the divine. Hence superlative darkness contains a philosophical commitment to superlative transcendence. Superlative darkness makes an anti-empiricist claim, in that it is beyond any experience of light or dark. It also makes an anti-idealist claim, in that it is beyond any conception of light or dark. What results are contradictory, superlative concepts of “light beyond light,” the “brilliant darkness,” or the “ray of divine darkness.” With superlative darkness, there is a movement from an affirmative to a superlative experience of the divine, from a simple affirmation to an affirmation beyond all affirmation. Claiming to move beyond both experience and thought, superlative darkness harbors within itself an anti-humanism (beyond creaturely experience, beyond human thought), leading to a “superlative darkness” or, really, a kataphatic darkness. We should note that with superlative darkness we are brought to a certain limit, not only of language but of thought itself. The motif of darkness comes in here to indicate this limit. And it is a horizon that haunts every concept of darkness, the possibility of thinking the impossible.

This play between the possible and impossible finally brings us to the third mode – what we’ve been calling divine darkness. Divine darkness questions the metaphysical commitment of superlative darkness, and really this means questioning its fidelity to the principle of sufficient reason. Now, the interesting thing about superlative darkness is that, while it may subscribe to a minimal version of the principle of sufficient reason, it does not presume that we as human beings can have a knowledge of this reason. That everything that exists has a reason for existing may be the case, but whether or not we can know this reason is another matter altogether. Superlative darkness is thus an attenuated variant of the principle of sufficient reason.

Perhaps we should really call this the principle of sufficient divinity. The principle of sufficient divinity is composed of two statements: a statement on being, which states that something exists, even though that something may not be known by us (and is therefore “nothing” for us as human beings), and a statement on logic, which states that that something-that-exists is ordered and thus intelligible (though perhaps not intelligible to us as human beings). Superlative darkness still relies on a limit of the human as a guarantee of the transcendent being and logic of the divine, or that which is outside-the-human. The limit of human knowing becomes a kind of back-door means of knowing human limits, resulting in the sort of conciliatory knowledge one finds in many mystical texts.

Now, a divine darkness would take this and make of it a limit as well. This involves distinguishing two types of limit within darkness-mysticism generally speaking. There is, firstly, the limit of human knowing. Darkness is the limit of the human to comprehend that which lies beyond the human – but which, as beyond the human, may still be invested with being, order, and meaning. This in turn leads to a derivative knowing of this unknowing. And here, darkness indicates the conciliatory ability to comprehend the incomprehensibility of what remains, outside the human.

Then there is, secondly, the limit of that which cannot be known by us, the limit of the limit, as it were. With the limit of human knowing, there is still the presupposition of something outside that is simply a limit for us as human beings. The limit of the limit is not a constraint or boundary, but a “darkening” of the principle of sufficient divinity. It suggests that there is nothing outside, and that this nothing-outside is absolutely inaccessible. This leads not to a conciliatory knowing of unknowing, which is really a knowing of something that cannot be known. Instead, it is a negative knowing of nothing to know. There is nothing, and it cannot be known.

We’ve been tracing the motif of darkness in mystical texts, and the way in which the concept of darkness is often compounded, duplicitous, and enigmatic. Each of our examples stems from the Dionysian tradition of negative theology, or the via negativa. Each puts forth a concept of negation that is tied in some way to the motif of darkness, though darkness is not always negative for each of these thinkers. And each example reaches its limit in a concept of the divine that we have been “mis-reading” in terms of the horror of philosophy – the limits of the human, the unreliable knowledge of such limits, the human confronting something it can only name as unhuman. Such a darkness is not in any way an answer, much less a solution, to some of the issues we face today concerning climate change, posthumanism, or what Bataille once called “the congested planet.” In a way, thinking this type of darkness is doomed to failure, devolving as it does on its own limits.

And, perhaps, the greatest lesson from all this is the one repeatedly stated by Eckhart – that this darkness, in its unknowing, is not separate from us, but really within us as well. It is not a darkness “out there” in the great beyond, but an “outside” (to use Bataille’s term) that is co-extensive with the human at its absolute limit. It runs the gamut from the lowest to the highest, from the self to the planet, from the human to the unhuman. It is a sentiment echoed by Bataille when he speaks about darkness as a form of impossibility:

enter into a dead end. There all possibilities are exhausted; the “possible” slips away and the impossible prevails. To face the impossible – exorbitant, indubitable – when nothing is possible any longer is in my eyes to have an experience of the divine…