Years ago, I read a book by one of the Chaser team called American Hoax. Anyway, in part that book had been written because while Firth was in the US he had been chatting with people about politics and he mentioned in passing the US empire. “Hey, hey, hey, whoa, you need to hold on up there a second buddy – we’re the land of the free, the home of the brave. We ain’t got no empire, uh, uhhh, no way, no siree … by golly, by jingo, by gee, by gosh, by gum.”

This came as something of a surprise to Chris Firth, and to me too as I was reading along. The idea that US citizens didn’t believe they had an empire, well, and that they could quote ee cummings, both seemed rather remarkable at the time. I suspect this little fact might come as something of a surprise most of the 95% of the world that are not citizens of the US. If you do decide to read this book, and you should read it, you should also consider reading the Blow Back Series. It focuses on some of the more recent issues raised here in much more depth.

This book is stunningly good. It is very clear and makes connections to the developments of science, technology and communications that fundamentally changed both the nature of war while also changing the nature of ‘empire’ building throughout the twentieth century. Those changes were particularly seen in how the physical control of populations became increasingly less relevant – and so the need for territorial expansion also diminished.

The book starts from the earliest days of the USA and follows its various imperial ambitions and realisations up to the present day. It is repeatedly said that this expansion was seen as pushing a splinter into the soul of the US. Throughout US history people have seen empire building as something that would ultimately destroy the republic.

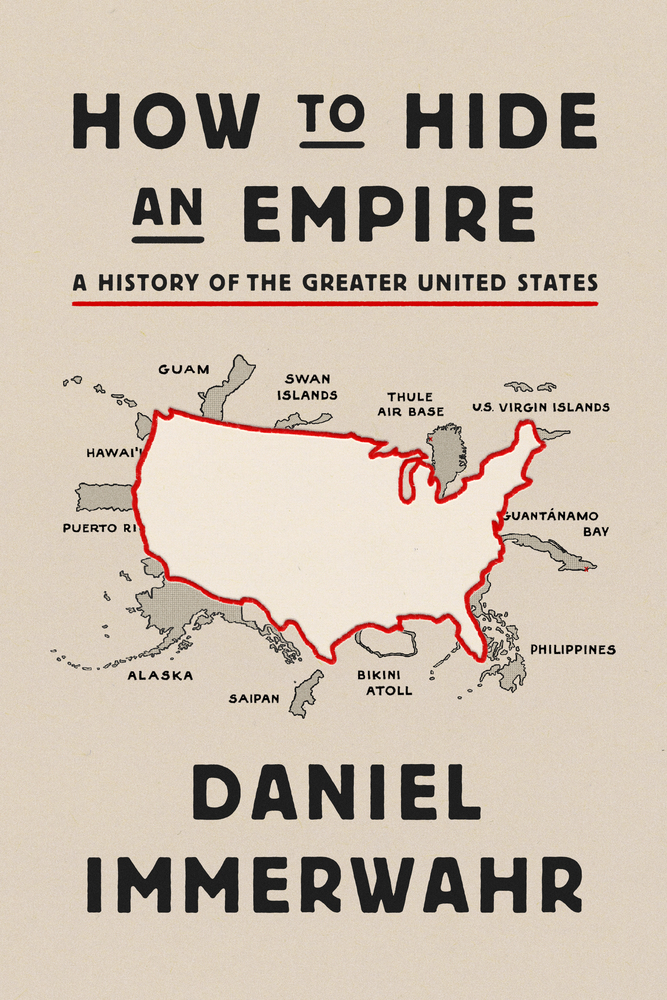

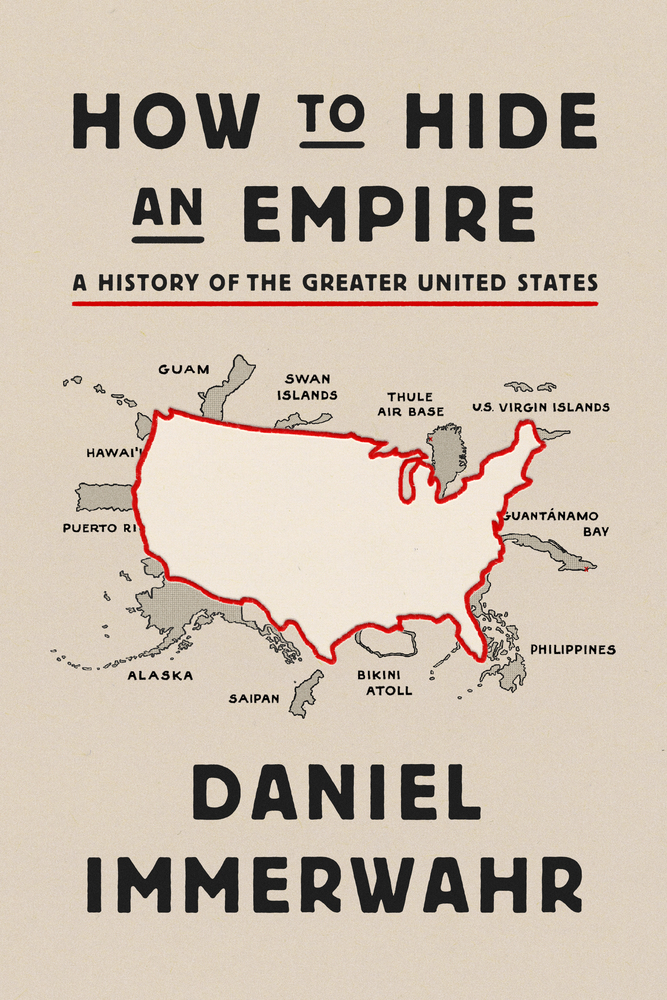

I’m fascinated by how we use images to define ourselves. One of the images that is used to define the USA is its flag, of course. I hadn’t realised that there is a law requiring the flag to change if a new state is incorporated into the union. The other image that is immediately associated with the US, something that is also immediately recognisable across the globe, is the ‘logo map’ of the nation. And what is interesting about this logo is that it is not accurate. Not only does the image we have of the US in our minds only really include the mainland ‘from sea to shining sea’ (even if those seas are oceans), we also know that it should probably include Hawaii and Alaska too, as well as Puerto Rico, and American Samoa, and… which is the point of this book, if you see what I mean.

There’s a nice bit in this where the US decided to claim a series of islands in the Pacific, only to learn that they had claimed them as part of their territory a hundred odd years before – ‘oh, that old thing… I’d completely forgotten I ever even owned it’. As the people of Puerto Rico have been learning for a very long time, being a territory of the US can come at quite a price, even if people on the main land sometimes forget you are part of their nation. The histories of Puerto Rico, The Philippines, and other places under the protection of the US government often proved anything but cheerful. A lot of this history is catastrophic and barbaric. But this is all part of the US ‘taking up the white man’s burden’ – which was a poem written by Kipling to encourage the US in the Philippine-American War. The author discusses the water cure in this – something I read about years ago in a much more brutal account than is given here – with US soldiers literally jumping onto the stomachs of their prisoners after they had bloated them with water. But as the author says, even his less extreme version is reminiscent of the more modern ‘cure’ of water boarding. Love and marriage, torture and conquest…time passes, little changes.

The need for colonies more generally arose with confined European nations needing access to commodities that they simply did not have in their own lands. Especially important was rubber – which lead King Leopold of Belgium to provide Joseph Conrad with endless material for his novel, Heart of Darkness, something The Congo has yet to recover from. Because the US is so large, it also had ready-made access to many commodities – minerals, metals, and so on – that meant it was relatively independent for these from other nations. However, this was certainly not true of guano – the miracle fertiliser derived from bird shit. Gaining control of guano islands was therefore an essential part of early US expansion.

Where I found this book particularly interesting was in its discussion of the part played by restrictions upon the US in terms of access to natural products (rubber in particular) and how these restrictions encouraged production of synthetic versions of these that often ended up being better than the originals. But the other thing this did was to make it less necessary for the US to literally dominate countries in the ways the UK had with its empire (upon which, the sun never set). As the case of the Philippines made clear, the US could have a territory while the average US citizen in the street of logo map USA wouldn’t have a clue. But controlling these territories often proved more effort than the US was happy to expend.

I can’t say that Douglas MacArthur comes out of this book smelling of roses – his return to liberate the Philippines (and his being forced out in the first place) read like bizarre stuff ups of the worst kind.

What became clear as planes and technologies improved, was that you could build an empire, and control the world, without engaging in very much territorial expansion at all. Territory was often difficult to conquer and even harder to hold – whereas, modern technology, especially planes, radio communication, and more recently drones, have meant that you can build pointillist empires. An island here, a military base there, an airfield over the other side of that, and your friends and enemies can be kept in place and trade routes maintained and everything can be kept both hunky and dory.

This book similarly brings in the idea of the role the US has played in making English a world language and the nature of globalisation when you can make the rules (and then ignore them when you like). That is, when you are the mono-pole of a global power system.

Whether or not the US empire proves to be overreach, whether blow back ever becomes so intense that even US citizens start to notice the legacy of their empire, or if peak oil eventually makes pointillist empires no longer viable and therefore forces empire builders back towards territorial expansion are things we will have to watch and see. This is a fascinating book, one I highly recommend – but read the Blow Back ones too.