What do you think?

Rate this book

88 pages, Hardcover

First published September 25, 2018

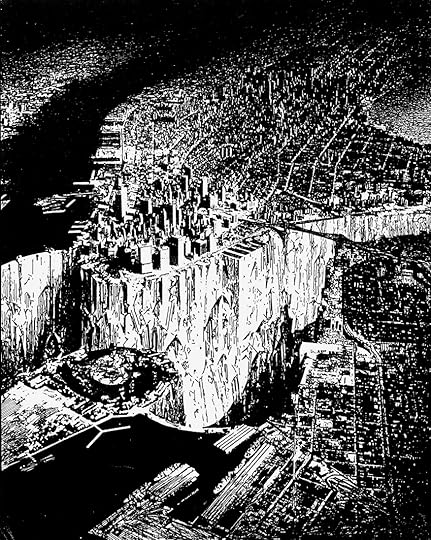

. . .the whole works, the entire workings of the universal is destruction and annihilation, devastation and ruination, how on earth can I say this right, in other words there is no dichotomy at work here, no such thing exists, it is imbecilic to talk about antithetical forces, two opposed sides, a reality describable in terms of mutually complementary concepts, silly to talk about good and evil, because all is evil, or else nothing is, for total reality can only be seen as continual destruction, permanent catastrophe, reality is catastrophe, this is what we inhabit, from the most miniscule subatomic particle to the greatest planetary dimensions, everything, do you understand, and again I am not addressing anyone in particular, everything plays the roles of both perpetrator and victim in this drama of inevitable catastrophe, therefore we simply cannot do otherwise than acknowledge this, and deal with the makeup of destruction, for instance the enormous forces that are shaping our Earth at every moment, we must confront the fact of war on Earth, because there is war in the Universe, and here comes Melville again with his brutal notion, that there is all of this and God is nowhere, that benevolent God the creator and judge is nowhere to be found, but instead we have Satan, and nothing but Satan, do you understand?!, by 1851 Melville ALREADY KNEW that only that Emptiness of Satan exists. . .so therefore we must build a monument to the absurd dignity and melancholy of human resistance, in the vicinity of Melville, Lowry, Woods, Krasznahorkai and melville, using 33 Thomas Street. This is just true!! This is why Korin went to NYC - someone's gotta do it!